1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...24

Figure 1.7 Demonstration of the cranial drawer test. One hand is placed on the distal femur with the thumb on the lateral fabella and the index finger on the patella. The other hand is placed on the proximal tibia with the thumb on the fibular head and the index finger on the tibial tuberosity. The goal is to move the hand on the proximal tibia cranially while holding the hand on the distal femur stable.

The make‐up of the craniomedial and caudolateral bands of the CCL can explain why it is possible for the cranial drawer test to be positive in flexion even if it is negative in extension. The craniomedial band is the primary supporter of tibial translation and tends to degenerate first. During range of motion, it is taut in both flexion and extension. The caudolateral band is a secondary supporter of tibial translation and is taut in extension but lax in flexion. Therefore, if the craniomedial band is torn, cranial drawer will be absent in extension but present in flexion. Lack of cranial drawer may indicate tearing of the caudolateral band with an intact craniomedial band or subtle tearing of the craniomedial band or both the craniomedial and caudolateral band. In anxious or nervous patients or those with negative cranial drawer, the authors recommend performing a sedated examination to ensure there is no instability. Unfortunately, when chronic periarticular fibrosis or advanced OA is present, cranial drawer may be negative due to the presence of significant fibrous tissue or permeant translation of the tibia in relation to the femur. Skeletally immature patients often exhibit some physiological cranial drawer (“puppy drawer”) of up to about 3–5 mm. However, there should be an abrupt stop point at the end of cranial drawer to differentiate this from pathological cranial drawer.

The tibial compression test ( Figure 1.8), while still a passive test, aims to mimic load bearing of the stifle. The operator may stand either behind (caudal) the patient or behind and slightly to the side (caudal and lateral). One hand is placed on the distal femur with the thumb on the lateral fabella and the index finger on the patella. The other hand is used to hold the metatarsals and tarsocrural joint. With the stifle held stable, the tarsocrural joint is flexed and extended. The clinician observes for a cranial‐to‐caudal motion of the tibial tuberosity indicating pathology of the CCL. Mistakes made by the inexperienced operator stem from trying to flex and extend both the stifle and tarsocrural joint simultaneously. In addition, the stifle should be held in a sagittal plane with no excessive internal or external rotation. Holding the stifle internally rotated can lead to a false positive of tibial thrust.

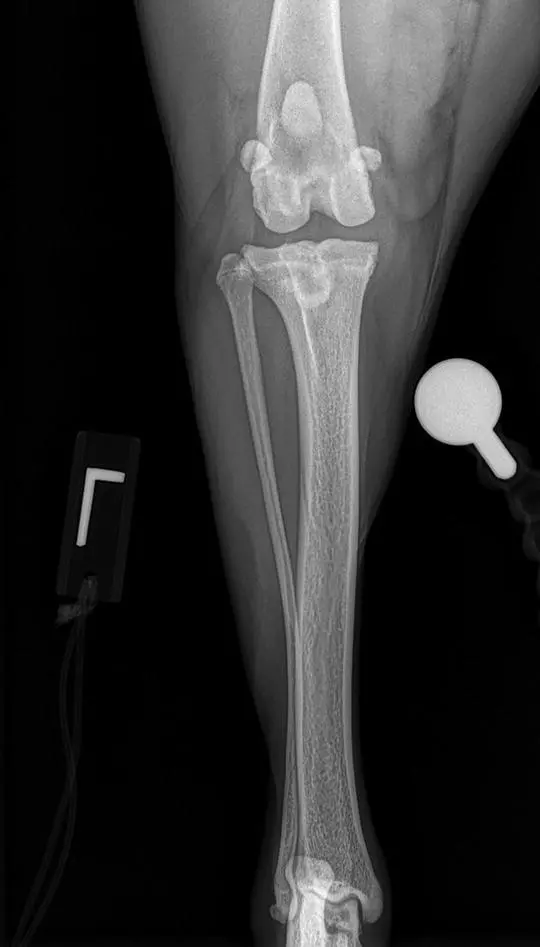

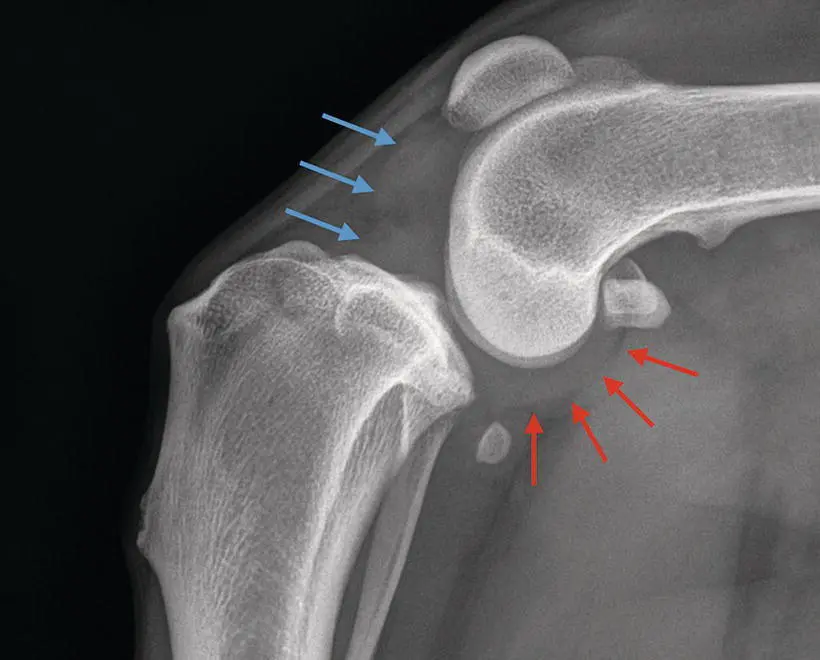

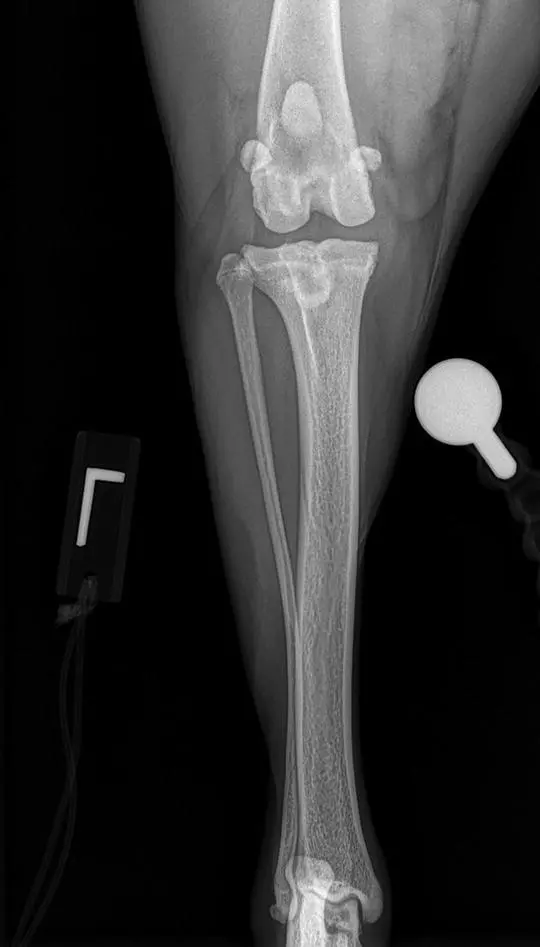

Diagnostic imaging of the stifle in patients with CCL pathology is usually centered around radiographic evaluation. Radiographic examination is warranted in every case of hindlimb lameness even if surgical intervention is not an option. It should be suggested that good‐quality orthogonal views of both the affected and unaffected stifles should be performed ( Figures 1.9and 1.10). While the CCL itself is not visible on radiographs (unless associated with an avulsion of the CCL), there are two key findings that can be appreciated: osteoarthritic changes and intraarticular changes (meniscal edema, synovial hyperplasia, and joint effusion).

Figure 1.8 Demonstration of the tibial compression test. One hand is placed on the distal femur with the thumb on the lateral fabella and the index finger on the patella. The other hand is used to hold the metatarsals and tarsocrural joint. With the stifle held stable, the tarsocrural joint is flexed and extended. The clinician observes for a cranial‐to‐caudal motion of the tibial tuberosity indicating pathology of the CCL.

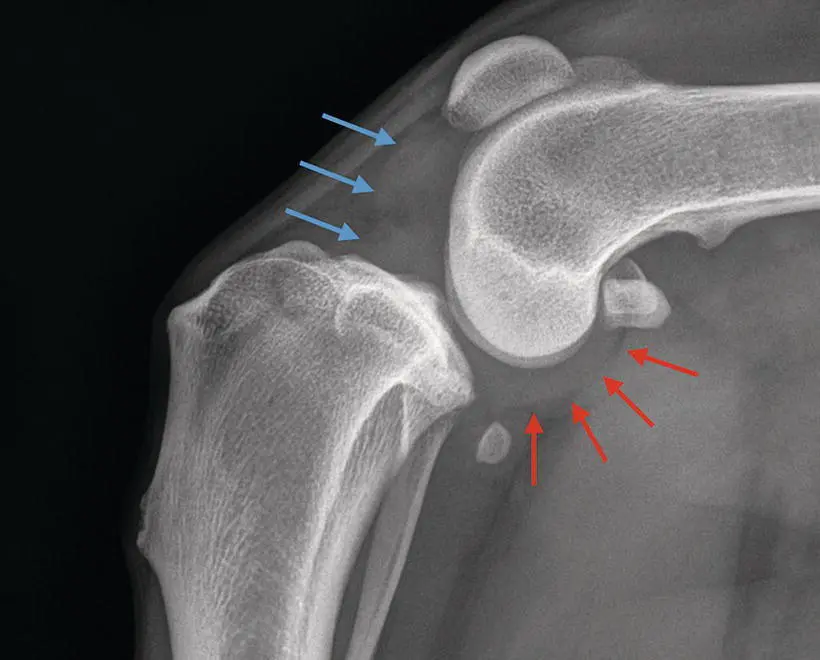

The earliest finding of CCL pathology is the presence of joint effusion ( Figure 1.11). This is noted by cranial displacement of the infrapatellar fat pad on the lateral view. The normal fat pad should be triangular in shape and located adjacent to the cranial margin of the femoral condyles and the cranial aspect of the tibial condyles. In most cases, any displacement from these normal margins is consistent with the presence of joint effusion. In addition, there may be displacement of the caudal joint capsule ( Figure 1.11). The degree of joint effusion in some cases can be roughly correlated with the degree of CCL pathology. Generally, patients with competent partial CCL pathology will have less joint effusion than patients with incompetent or complete CCL pathology. Evidence of likely synovitis can be noted as subtle regions of sclerosis noted on the caudal aspect of the trochlear groove as seen on the lateral view.

Degenerative changes can readily be seen in patients with CCL pathology ( Figure 1.12). In particular, changes will be noted at the proximal trochlear groove, lateral and medial femoral trochlea, distal pole of the patella (patella apex), caudal tibial plateau, medial and lateral aspects of the tibial condyle margins, and both fabellae. In some cases, the sesamoid bone of the popliteal muscle can be displaced proximally and/or caudally. The importance of taking contralateral radiographs at the time of initial diagnosis is for the evaluation of OA and joint effusion as well as detection of other pathologies that might exist. If noted on the contralateral stifle (even in the face of joint stability), one should assume there is already CCL pathology present and the likelihood of joint instability developing is high. If this is present, it is important to educate the owner regarding this finding.

Figure 1.9 A lateral radiograph documenting appropriate positioning of the stifle. Notice there is superimposition of the femoral condyles and the tibial plateau demonstrating a straight view in the sagittal plane.

Figure 1.10 A cranial‐caudal radiograph documenting appropriate position of the stifle. Notice how the calcaneus intersects the center of the trochlear ridge of the talus demonstrating a straight view in the frontal plane.

A number of methods for stifle stabilization exist. They are commonly characterized as extraarticular stabilization, intraarticular stabilization, and osteotomy modifying procedures. One of the complicating factors of stifle stabilization (and indeed, one of the reasons for the existence of so many surgical procedures) is the lack of definitive guidelines for what constitutes a successful postoperative outcome.

Figure 1.11 Evidence of joint effusion in the stifle of a patient with CCL pathology. In the caudal compartment, there is displacement of the joint capsule as can be noted by the red arrows. The opacity in the cranial compartment (blue arrows) is joint effusion that is displacing the fat pad cranially.

Читать дальше