After passing a great number of new islands we got into open water off Taimur Island, and steamed in still weather through the sound to the northeast. At 5 in the afternoon I saw from the crow’s-nest thick ice ahead, which blocked farther progress. It stretched from Taimur Island right across to the islands south of it. On the ice bearded seals ( Phoca barbata ) were to be seen in all directions, and we saw one walrus. We approached the ice to make fast to it, but the Fram had got into dead-water, and made hardly any way, in spite of the engine going full pressure. It was such slow work that I thought I would row ahead to shoot seal. In the meantime the Fram advanced slowly to the edge of the ice with her machinery still going at full speed.

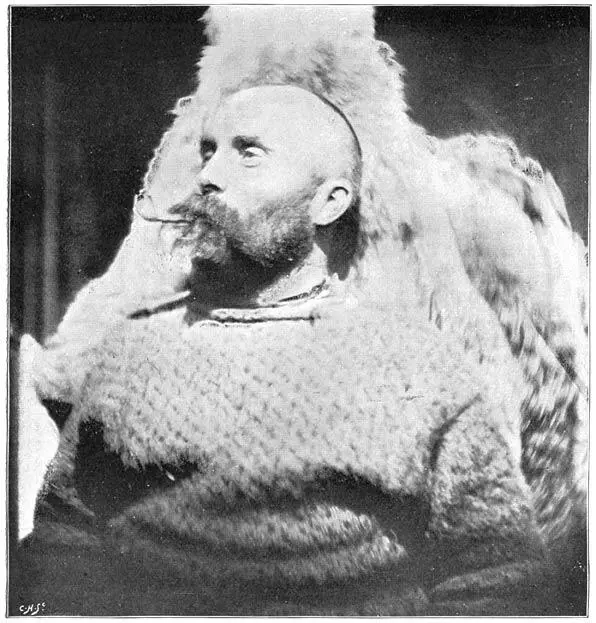

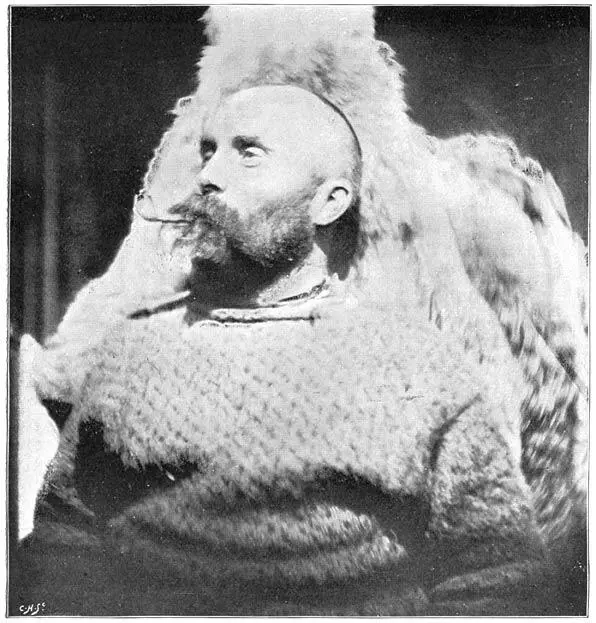

Bernt Bentzen

( From a photograph taken in December, 1893 )

For the moment we had simply to give up all thoughts of getting on. It was most likely, indeed, that only a few miles of solid ice lay between us and the probably open Taimur Sea; but to break through this ice was an impossibility. It was too thick, and there were no openings in it. Nordenskiöld had steamed through here earlier in the year (August 18, 1878) without the slightest hinderance, 4and here, perhaps, our hopes, for this year at any rate, were to be wrecked. It was not possible that the ice should melt before winter set in in earnest. The only thing to save us would be a proper storm from the southwest. Our other slight hope lay in the possibility that Nordenskiöld’s Taimur Sound farther south might be open, and that we might manage to get the Fram through there, in spite of Nordenskiöld having said distinctly “that it is too shallow to allow of the passage of vessels of any size.”

After having been out in the kayak and boat and shot some seals, we went on to anchor in a bay that lay rather farther south, where it seemed as if there would be a little shelter in case of a storm. We wanted now to have a thorough cleaning out of the boiler, a very necessary operation. It took us more than one watch to steam a distance we could have rowed in half an hour or less. We could hardly get on at all for the dead-water, and we swept the whole sea along with us. It is a peculiar phenomenon, this dead-water. We had at present a better opportunity of studying it than we desired. It occurs where a surface layer of fresh water rests upon the salt water of the sea, and this fresh water is carried along with the ship, gliding on the heavier sea beneath as if on a fixed foundation. The difference between the two strata was in this case so great that, while we had drinking-water on the surface, the water we got from the bottom cock of the engine-room was far too salt to be used for the boiler. Dead-water manifests itself in the form of larger or smaller ripples or waves stretching across the wake, the one behind the other, arising sometimes as far forward as almost amidships. We made loops in our course, turned sometimes right round, tried all sorts of antics to get clear of it, but to very little purpose. The moment the engine stopped it seemed as if the ship were sucked back. In spite of the Fram’s weight and the momentum she usually has, we could in the present instance go at full speed till within a fathom or two of the edge of the ice, and hardly feel a shock when she touched.

Just as we were approaching we saw a fox jumping backward and forward on the ice, taking the most wonderful leaps and enjoying life. Sverdrup sent a ball from the forecastle which put an end to it on the spot.

About midday two bears were seen on land, but they disappeared before we got in to shoot them.

The number of seals to be seen in every direction was something extraordinary, and it seemed to me that this would be an uncommonly good hunting-ground. The flocks I saw this first day on the ice reminded me of the crested-seal hunting-grounds on the west coast of Greenland.

This experience of ours may appear to contrast strangely with that of the Vega expedition. Nordenskiöld writes of this sea, comparing it with the sea to the north and east of Spitzbergen: “Another striking difference is the scarcity of warm-blooded animals in this region as yet unvisited by the hunter. We had not seen a single bird in the whole course of the day, a thing that had never before happened to me on a summer voyage in the Arctic regions, and we had hardly seen a seal.” The fact that they had not seen a seal is simply enough explained by the absence of ice. From my impression of it, the region must, on the contrary, abound in seals. Nordenskiöld himself says that “numbers of seals, both Phoca barbata and Phoca hispida , were to be seen” on the ice in Taimur Strait.

So this was all the progress we had made up to the end of August. On August 18, 1878, Nordenskiöld had passed through this sound, and on the 19th and 20th passed Cape Chelyuskin, but here was an impenetrable mass of ice frozen on to the land lying in our way at the end of the month. The prospect was anything but cheering. Were the many prophets of evil—there is never any scarcity of them —to prove right even at this early stage of the undertaking? No! The Taimur Strait must be attempted, and should this attempt fail another last one should be made outside all the islands again. Possibly the ice masses out there might in the meantime have drifted and left an open way. We could not stop here.

September came in with a still, melancholy snowfall, and this desolate land, with its low, rounded heights, soon lay under a deep covering. It did not add to our cheerfulness to see winter thus gently and noiselessly ushered in after an all too short summer.

On September 2d the boiler was ready at last, was filled with fresh water from the sea surface, and we prepared to start. While this preparation was going on Sverdrup and I went ashore to have a look after reindeer. The snow was lying thick, and if it had not been so wet we could have used our snow-shoes. As it was, we tramped about in the heavy slush without them, and without seeing so much as the track of a beast of any kind. A forlorn land, indeed! Most of the birds of passage had already taken their way south; we had met small flocks of them at sea. They were collecting for the great flight to the sunshine, and we, poor souls, could not help wishing that it were possible to send news and greeting with them. A few solitary Arctic and ordinary gulls were our only company now. One day I found a belated straggler of a goose sitting on the edge of the ice.

We steamed south in the evening, but still followed by the dead-water. According to Nordenskiöld’s map, it was only about 20 miles to Taimur Strait, but we were the whole night doing this distance. Our speed was reduced to about a fifth part of what it would otherwise have been. At 6 A.M. (September 3d) we got in among some thin ice that scraped the dead-water off us. The change was noticeable at once. As the Fram cut into the ice crust she gave a sort of spring forward, and, after this, went on at her ordinary speed; and henceforth we had very little more trouble with dead-water.

We found what, according to the map, was Taimur Strait entirely blocked with ice, and we held farther south, to see if we could not come upon some other strait or passage. It was not an easy matter finding our way by the map. We had not seen Hovgaard’s Islands, marked as lying north of the entrance to Taimur Strait; yet the weather was so beautifully clear that it seemed unlikely they could have escaped us if they lay where Nordenskiöld’s sketch-map places them. On the other hand, we saw several islands in the offing. These, however, lay so far out that it is not probable that Nordenskiöld saw them, as the weather was thick when he was here; and, besides, it is impossible that islands lying many miles out at sea could have been mapped as close to land, with only a narrow sound separating them from it. Farther south we found a narrow open strait or fjord, which we steamed into, in order if possible to get some better idea of the lay of the land. I sat up in the crow’s-nest, hoping for a general clearing up of matters; but the prospect of this seemed to recede farther and farther. What we now had to the north of us, and what I had taken to be a projection of the mainland, proved to be an island; but the fjord wound on farther inland. Now it got narrower—presently it widened out again. The mystery thickened. Could this be Taimur Strait, after all? A dead calm on the sea. Fog everywhere over the land. It was wellnigh impossible to distinguish the smooth surface of the water from the ice, and the ice from the snow-covered land. Everything is so strangely still and dead. The sea rises and falls with each twist of the fjord through the silent land of mists. Now we have open water ahead, now more ice, and it is impossible to make sure which it is. Is this Taimur Strait? Are we getting through? A whole year is at stake! … No! here we stop—nothing but ice ahead. No! it is only smooth water with the snowy land reflected in it. This must be Taimur Strait!

Читать дальше