We reached the slant of the valley almost at the same time—a leap or two to get up on some big boulders, and the moment had come—I must shoot, though the shot was a long one. When the smoke cleared away I saw the big buck trailing a broken hind-leg. When their leader stopped, the whole flock turned and ran in a ring round the poor animal. They could not understand what was happening, and strayed about wildly with the balls whistling round them. Then off they went down the side of the valley again, leaving another of their number behind with a broken leg. I tore after them, across the valley and up the other side, in the hope of getting another shot, but gave that up and turned back to make sure of the two wounded ones. At the bottom of the valley stood one of the victims awaiting its fate. It looked imploringly at me, and then, just as I was going forward to shoot it, made off much quicker than I could have thought it possible for an animal on three legs to go. Sure of my shot, of course I missed; and now began a chase, which ended in the poor beast, blocked in every other direction, rushing down towards the sea and wading into a small lagoon on the shore, whence I feared it might get right out into the sea. At last it got its quietus there in the water. The other one was not far off, and a ball soon put an end to its sufferings also. As I was proceeding to rip it up, Henriksen and Johansen appeared; they had just shot a bear a little farther south.

A dead bear on Reindeer Island (August 21, 1893)

( From a Photograph )

After disembowelling the reindeer, we went towards the boat again, meeting Sverdrup on the way. It was now well on in the morning, and as I considered that we had already spent too much time here, I was impatient to push northward. While Sverdrup and some of the others went on board to get ready for the start, the rest of us rowed south to fetch our two reindeer and our bear. A strong breeze had begun to blow from the northeast, and as it would be hard work for us to row back against it, I had asked Sverdrup to come and meet us with the Fram , if the soundings permitted of his doing so. We saw quantities of seal and white fish along the shore, but we had not time to go after them; all we wanted now was to get south, and in the first place to pick up the bear. When we came near the place where we expected to find it, we did see a large white heap resembling a bear lying on the ground, and I was sure it must be the dead one, but Henriksen maintained that it was not. We went ashore and approached it, as it lay motionless on a grassy bank. I still felt a strong suspicion that it had already had all the shot it wanted. We drew nearer and nearer, but it gave no sign of life. I looked into Henriksen’s honest face, to make sure that they were not playing a trick on me; but he was staring fixedly at the bear. As I looked, two shots went off, and to my astonishment the great creature bounded into the air, still dazed with sleep. Poor beast! it was a harsh awakening. Another shot, and it fell lifeless.

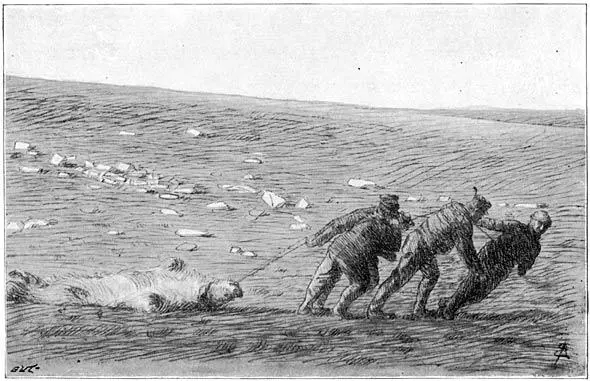

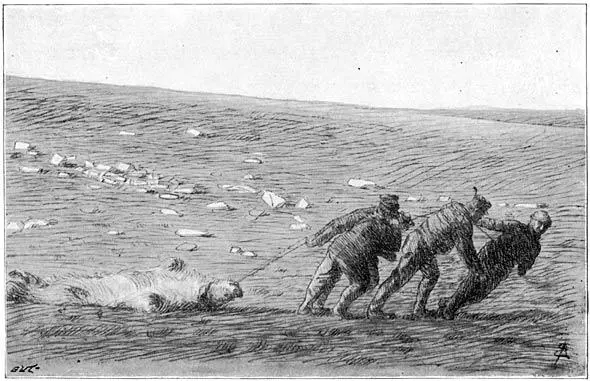

“We first tried to drag the bears”

( By A. Eiebakke, from a Photograph )

We first tried to drag the bears down to the boat, but they were too heavy for us; and we now had a hard piece of work skinning and cutting them up, and carrying down all we wanted. But, bad as it was, trudging through the soft clay with heavy quarters of bear on our backs, there was worse awaiting us on the beach. The tide had risen, and at the same time the waves had got larger and swamped the boat, and were now breaking over it. Guns and ammunition were soaking in the water; bits of bread, our only provision, floated round, and the butter-dish lay at the bottom, with no butter in it. It required no small exertion to get the boat drawn up out of this heavy surf and emptied of water. Luckily, it had received no injury, as the beach was of a soft sand; but the sand had penetrated with the water everywhere, even into the most delicate parts of the locks of our rifles. But worst of all was the loss of our provisions, for now we were ravenously hungry. We had to make the best of a bad business, and eat pieces of bread soaked in sea-water and flavored with several varieties of dirt. On this occasion, too, I lost my sketch-book, with some sketches that were of value to me.

It was no easy task to get our heavy game into the boat with these big waves breaking on the flat beach. We had to keep the boat outside the surf, and haul both skins and flesh on board with a line; a good deal of water came with them, but there was no help for it. And then we had to row north along the shore against the wind and sea as hard as we could. It was very tough work. The wind had increased, and it was all we could do to make headway against it. Seals were diving round us, white whales coming and going, but we had no eyes for them now. Suddenly Henriksen called out that there was a bear on the point in front. I turned round, and there stood a beautiful white fellow rummaging among the flotsam on the beach. As we had no time to shoot it, we rowed on, and it went slowly in front of us northward along the shore. At last, with great exertions, we reached the bay where we were to put in for the reindeer. The bear was there before us. It had not seen the boat hitherto; but now it got scent of us, and came nearer. It was a tempting shot. I had my finger on the trigger several times, but did not draw it. After all, we had no use for the animal; it was quite as much as we could do to stow away what we had already. It made a beautiful target of itself by getting up on a stone to have a better scent, and looked about, and, after a careful survey, it turned round and set off inland at an easy trot.

The surf was by this time still heavier. It was a flat, shallow shore, and the waves broke a good way out from land. We rowed in till the boat touched ground and the breakers began to wash over us. The only way of getting ashore was to jump into the sea and wade. But getting the reindeer on board was another matter. There was no better landing-place farther north, and hard as it was to give up the excellent meat after all our trouble, it seemed to me there was nothing else for it, and we rowed off towards our ship.

It was the hardest row I ever had a hand in. It went pretty well to begin with; we had the current with us, and got quickly out from land; but presently the wind rose, the current slackened, and wave after wave broke over us. After incredible toil we had at last only a short way to go. I cheered up the good fellows as best I could, reminding them of the smoking hot tea that awaited them after a few more tough pulls, and picturing all the good things in store for them. We really were all pretty well done up now, but we still took a good grip of the oars, soaking wet as we were from the sea constantly breaking over us, for of course none of us had thought of such things as oilskins in yesterday’s beautiful weather. But we soon saw that with all our pulling and toiling the boat was making no headway whatever. Apart from the wind and the sea we had the current dead against us here; all our exertions were of no avail. We pulled till our finger-tips felt as if they were bursting; but the most we could manage was to keep the boat where it was; if we slackened an instant it drifted back. I tried to encourage my comrades: “ Now we made a little way! It was just strength that was needed!” But all to no purpose. The wind whistled round our ears, and the spray dashed over us. It was maddening to be so near the ship that it seemed as if we could almost reach out to her, and yet feel that it was impossible to get on any farther. We had to go in under the land again, where we had the current with us, and here we did succeed in making a little progress. We rowed hard till we were about abreast of the ship; then we once more tried to sheer across to her, but no sooner did we get into the current again than it mercilessly drove us back. Beaten again! And again we tried the same manœuvre with the same result. Now we saw them lowering a buoy from the ship—if we could only reach it we were saved; but we did not reach it. They were not exactly blessings that we poured on those on board. Why the deuce could they not bear down to us when they saw the straits we were in; or why, at any rate, could they not ease up the anchor, and let the ship drift a little in our direction? They saw how little was needed to enable us to reach them. Perhaps they had their reasons.

Читать дальше