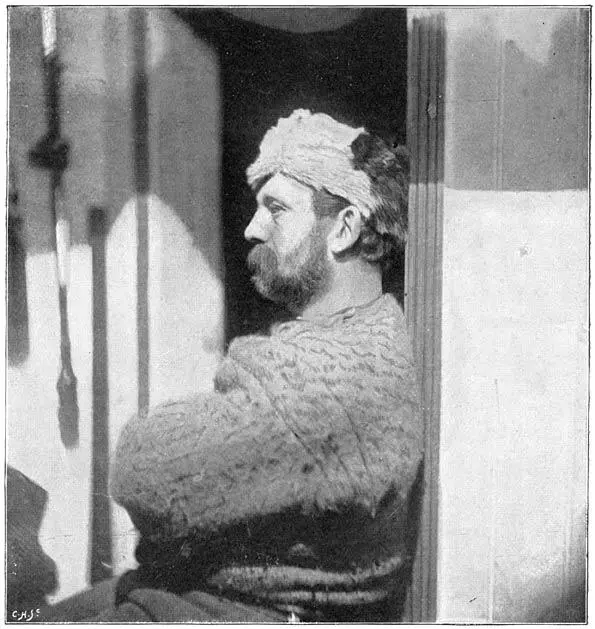

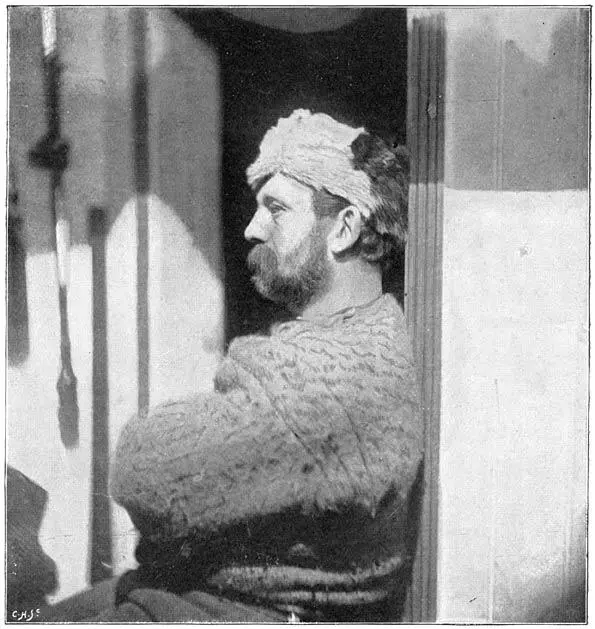

Bernard Nordahl

( From a photograph taken in December, 1893 )

We would make our last desperate attempt. We went at it with a will. Every muscle was strained to the utmost—it was only the buoy we had to reach this time. But to our rage we now saw the buoy being hauled up. We rowed a little way on, to the windward of the Fram , and then tried again to sheer over. This time we got nearer her than we had ever been before; but we were disappointed in still seeing no buoy, and none was thrown over; there was not even a man to be seen on deck. We roared like madmen for a buoy—we had no strength left for another attempt. It was not a pleasing prospect to have to drift back, and go ashore again in our wet clothes—we would get on board! Once more we yelled like wild Indians, and now they came rushing aft and threw out the buoy in our direction. One more cry to my mates that we must put our last strength into the work. There were only a few boat lengths to cover; we bent to our oars with a will. Now there were three boat lengths. Another desperate spurt. Now there were two and a half boat lengths—presently two—then only one! A few more frantic pulls, and there was a little less. “Now, boys, one or two more hard pulls and it’s over! Hard! hard!! Keep to it! Now another! Don’t give up! One more! There, we have it!!! ” And one joyful sigh of relief passed round the boat. “Keep the oars going or the rope will break. Row, boys!” And row we did, and soon they had hauled us alongside of the Fram . Not till we were lying there getting our bearskins and flesh hauled on board did we really know what we had had to fight against. The current was running along the side of the ship like a rapid river. At last we were actually on board. It was evening by this time, and it was splendid to get some good hot food and then stretch one’s limbs in a comfortable dry berth. There is a satisfaction in feeling that one has exerted one’s self to some purpose. Here was the net result of four-and-twenty hours’ hard toil: we had shot two reindeer which we did not get, got two bears that we had no use for, and had totally ruined one suit of clothes. Two washings had not the smallest effect upon them, and they hung on deck to air for the rest of this trip.

I slept badly that night, for this is what I find in my diary: “Got on board after what I think was the hardest row I ever had. Slept well for a little, but am now lying tossing about in my berth, unable to sleep. Is it the coffee I drank after supper? or the cold tea I drank when I awoke with a burning thirst? I shut my eyes and try again time after time, but to no purpose. And now memory’s airy visions steal softly over my soul. Gleam after gleam breaks through the mist. I see before me sunlit landscapes—smiling fields and meadows, green, leafy trees and woods, and blue mountain ridges. The singing of the steam in the boiler-pipe turns to bell-ringing—church bells—ringing in Sabbath peace over Vestre-Aker on this beautiful summer morning. I am walking with father along the avenue of small birch-trees that mother planted, up towards the church, which lies on the height before us, pointing up into the blue sky and sending its call far over the country-side. From up there you can see a long way. Næsodden looks quite close in the clear air, especially on an autumn morning. And we give a quiet Sunday greeting to the people that drive past us, all going our way. What a look of Sunday happiness dwells on their faces!

“I did not think it all so delightful then, and would much rather have run off to the woods with my bow and arrow after squirrels—but now—how fair, how wonderfully beautiful that sunlit picture seems to me! The feeling of peace and happiness that even then no doubt made its impression, though only a passing one, comes back now with redoubled strength, and all nature seems one mighty, thrilling song of praise! Is it because of the contrast with this poor, barren, sunless land of mists—without a tree, without a bush—nothing but stones and clay? No peace in it either—nothing but an endless struggle to get north, always north, without a moment’s delay. Oh, how one yearns for a little careless happiness!”

Next day we were again ready to sail, and I tried to force the Fram on under steam against wind and current. But the current ran strong as a river, and we had to be specially careful with the helm; if we gave her the least thing too much she would take a sheer, and we knew there were shallows and rocks on all sides. We kept the lead going constantly. For a time all went well, and we made way slowly, but suddenly she took a sheer and refused to obey her helm. She went off to starboard. The lead indicated shallow water. The same moment came the order, “Let go the anchor!” And to the bottom it went with a rush and a clank. There we lay with 4 fathoms of water under the stern and 9 fathoms in front at the anchor. We were not a moment too soon. We got the Fram’s head straight to the wind, and tried again, time after time, but always with the same result. The attempt had to be given up. There was still the possibility of making our way out of the sound to leeward of the land, but the water got quickly shallow there, and we might come on rocks at any moment. We could have gone on in front with the boat and sounded, but I had already had more than enough of rowing in that current. For the present we must stay where we were and anoint ourselves with the ointment called Patience, a medicament of which every polar expedition ought to lay in a large supply. We hoped on for a change, but the current remained as it was, and the wind certainly did not decrease. I was in despair at having to lie here for nothing but this cursed current, with open sea outside, perhaps as far as Cape Chelyuskin, that eternal cape, whose name had been sounding in my ears for the last three weeks.

When I came on deck next morning (August 23d) winter had come. There was white snow on the deck, and on every little projection of the rigging where it had found shelter from the wind; white snow on the land, and white snow floating through the air. Oh, how the snow refreshes one’s soul, and drives away all the gloom and sadness from this sullen land of fogs! Look at it scattered so delicately, as if by a loving hand, over the stones and the grass-flats on shore! But wind and current are much as they were, and during the day the wind blows up to a regular storm, howling and rattling in the Fram’s rigging.

The following day (August 24th) I had quite made up my mind that we must get out some way or other. When I came on deck in the morning the wind had gone down considerably, and the current was not so strong. A boat would almost be able to row against it; anyhow one could be eased away by a line from the stern, and keep on taking soundings there, while we “kedged” the Fram with her anchor just clear of the bottom. But before having recourse to this last expedient I would make another attempt to go against the wind and the current. The engineers were ordered to put on as much pressure of steam as they dared, and the Fram was urged on at her top speed. Our surprise was not small when we saw that we were making way, and even at a tolerable rate. Soon we were out of the sound or “Knipa” (nipper) as we christened it, and could beat out to sea with steam and sail. Of course, we had, as usual, contrary wind and thick weather. There is ample space between every little bit of sunshine in these quarters.

Next day we kept on beating northward between the edge of the ice and the land. The open channel was broad to begin with, but farther north it became so narrow that we could often see the coast when we put about at the edge of the ice. At this time we passed many unknown islands and groups of islands. There was evidently plenty of occupation here, for any one who could spare the time, in making a chart of the coast. Our voyage had another aim, and all that we could do was to make a few occasional measurements of the same nature as Nordenskiöld had made before us.

Читать дальше