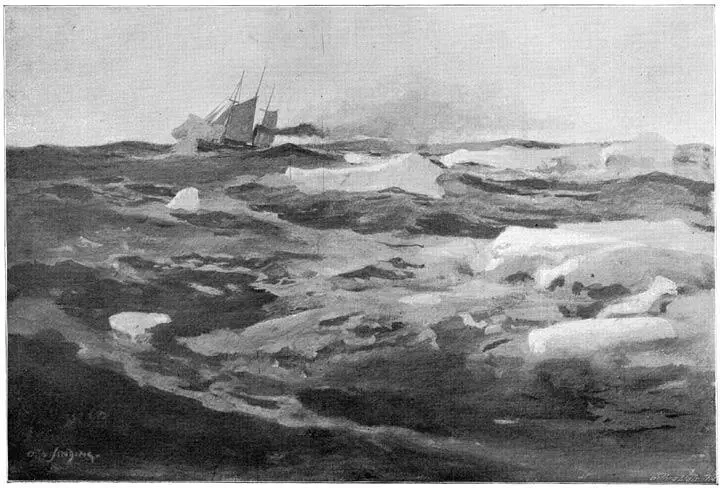

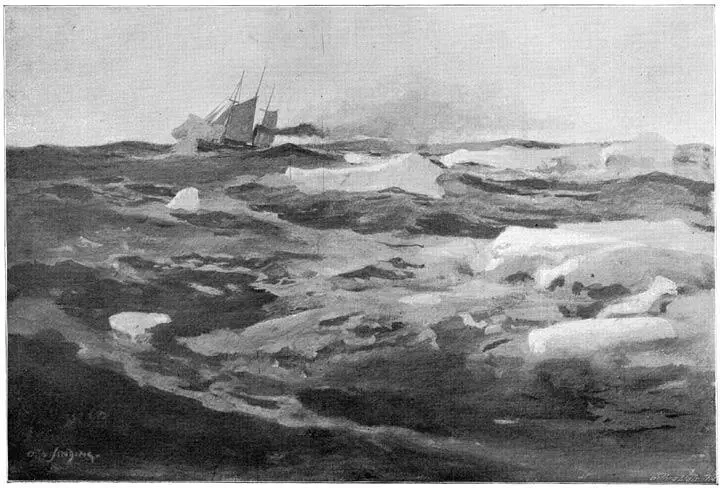

Thursday, August 17th. Still beating eastward under sail and steam through scattered ice, and along a margin of fixed ice. Still blowing hard, with a heavy sea as soon as we headed a little out from the ice.

The “Fram” in the Kara Sea

( By Otto Sinding )

Friday, August 18th. Continued storm. Stood southeast. At 4.30 A.M., Sverdrup, who had gone up into the crow’s-nest to look out for bears and walrus on the ice-floes, saw land to the south of us. At 10 A.M. I went up to look at it—we were then probably not more than 10 miles away from it. It was low land, seemingly of the same formation as Yalmal, with steep sand-banks, and grass-grown above. The sea grew shallower as we neared it. Not far from us, small icebergs lay aground. The lead showed steadily less and less water; by 11.30 A.m. there were only some 8 fathoms; then, to our surprise, the bottom suddenly fell to 20 fathoms, and after that we found steadily increasing depth. Between the land and the blocks of stranded ice on our lee there appeared to be a channel with rather deeper water and not so much ice aground in it. It seemed difficult to conceive that there should be undiscovered land here, where both Nordenskiöld and Edward Johansen, and possibly several Russians, had passed without seeing anything. Our observations, however, were incontestable, and we immediately named the land Sverdrup’s Island, after its discoverer.

As there was still a great deal of ice to windward, we continued our southwesterly course, keeping as close to the wind as possible. The weather was clear, and at 8 o’clock we sighted the mainland, with Dickson’s Island ahead. It had been our intention to run in and anchor here, in order to put letters for home under a cairn, Captain Wiggins having promised to pick them up on his way to the Yenisei. But in the meantime the wind had fallen: it was a favorable chance, and time was precious. So we gave up sending our post, and continued our course along the coast.

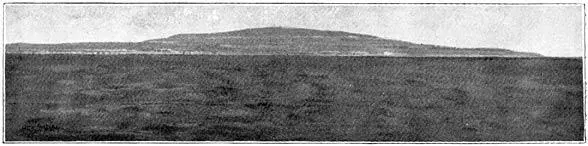

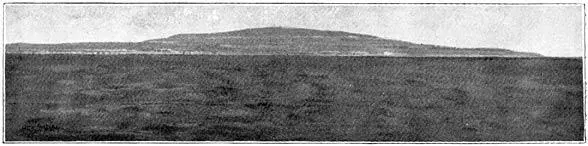

Ostrova Kamenni (Rocky Island), off the coast of Siberia

The country here was quite different from Yalmal. Though not very high, it was a hilly country, with patches and even large drifts of snow here and there, some of them lying close down by the shore. Next morning I sighted the southernmost of the Kamenni Islands. We took a tack in under it to see if there were animals of any kind, but could catch sight of none. The island rose evenly from the sea at all points, with steep shores. They consisted for the most part of rock, which was partly solid, partly broken up by the action of the weather into heaps of stones. It appeared to be a stratified rock, with strongly marked oblique strata. The island was also covered with quantities of gravel, sometimes mixed with larger stones; the whole of the northern point seemed to be a sand heap, with steep sand-banks towards the shore. The most noticeable feature of the island was its marked shore-lines. Near the top there was a specially pronounced one, which was like a sharp ledge on the west and north sides, and stretched across the island like a dark band. Nearer the beach were several other distinct ones. In form they all resembled the upper one with its steep ledges, and had evidently been formed in the same way—by the action of the sea, and more especially of the ice. Like the upper one, they also were most marked on the west and north sides of the island, which are those facing most to the open sea.

To the student of the history of the earth these marks of the former level of the sea are of great interest, showing as they do that the land has risen or the sea sunk since the time they were formed. Like Scandinavia, the whole of the north coast of Siberia has undergone these changes of level since the Great Ice Age.

It was strange that we saw none of the islands which, according to Nordenskiöld’s map, stretch in a line to the northeast from Kamenni Islands. On the other hand, I took the bearings of one or two other islands lying almost due east, and next morning we passed a small island farther north.

We saw few birds in this neighborhood—only a few flocks of geese, some Arctic gulls ( Lestris parasitica and L. buffonii ), and a few sea-gulls and tern.

On Sunday, August 20th, we had, for us, uncommonly fine weather—blue sea, brilliant sunshine, and light wind, still from the northeast. In the afternoon we ran in to the Kjellman Islands. These we could recognize from their position on Nordenskiöld’s map, but south of them we found many unknown ones. They all had smoothly rounded forms, these Kjellman Islands, like rocks that have been ground smooth by the glaciers of the Ice Age. The Fram anchored on the north side of the largest of them, and while the boiler was being refitted, some of us went ashore in the evening for some shooting. We had not left the ship when the mate, from the crow’s-nest, caught sight of reindeer. At once we were all agog; every one wanted to go ashore, and the mate was quite beside himself with the hunter’s fever, his eyes as big as saucers, and his hands trembling as though he were drunk. Not until we were in the boat had we time to look seriously for the mate’s reindeer. We looked in vain—not a living thing was to be seen in any direction. Yes—when we were close inshore we at last descried a large flock of geese waddling upward from the beach. We were base enough to let a conjecture escape us that these were the mate’s reindeer—a suspicion which he at first rejected with contempt. Gradually, however, his confidence oozed away. But it is possible to do an injustice even to a mate. The first thing I saw when I sprang ashore was old reindeer tracks. The mate had now the laugh on his side, ran from track to track, and swore that it was reindeer he had seen.

When we got up on to the first height we saw several reindeer on flat ground to the south of us; but, the wind being from the north, we had to go back and make our way south along the shore till we got to leeward of them. The only one who did not approve of this plan was the mate, who was in a state of feverish eagerness to rush straight at some reindeer he thought he had seen to the east, which, of course, was an absolutely certain way to clear the field of every one of them. He asked and received permission to remain behind with Hansen, who was to take a magnetic observation; but had to promise not to move till he got the order.

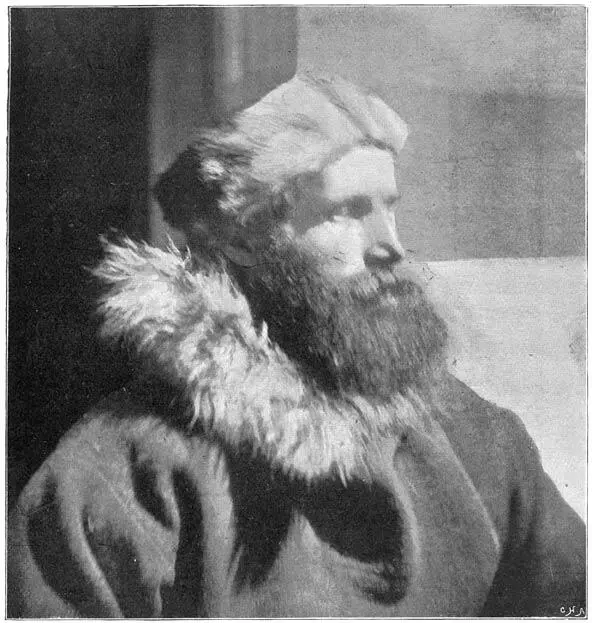

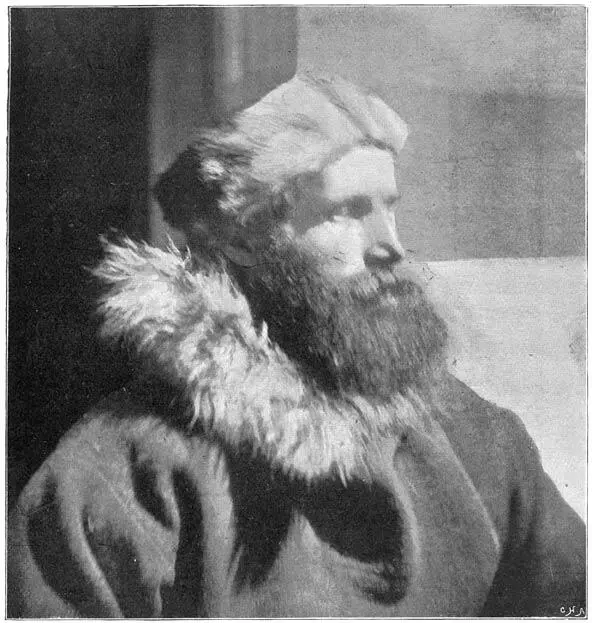

Theodor C. Jacobsen, mate of the “Fram”

( From a Photograph, December 11, 1893 )

On the way along the shore we passed one great flock of geese after another; they stretched their necks and waddled aside a little until we were quite near, and only then took flight; but we had no time to waste on such small game. A little farther on we caught sight of one or two reindeer we had not noticed before. We could easily have stalked them, but were afraid of getting to windward of the others, which were farther south. At last we got to leeward of these latter also, but they were grazing on flat ground, and it was anything but easy to stalk them—not a hillock, not a stone to hide behind. The only thing was to form a long line, advance as best we could, and, if possible, outflank them. In the meantime we had caught sight of another herd of reindeer farther to the north, but suddenly, to our astonishment, saw them tear off across the plain eastward, in all probability startled by the mate, who had not been able to keep quiet any longer.

Читать дальше