Nordenskiöld’s map marks at this place, “high mountain chains inland”; and this agrees with our observations, though I cannot assert that the mountains are of any considerable height. But when, in agreement with earlier maps, he marks at the same place, “high, rocky coast,” his terms are open to objection. The coast is, as already mentioned, quite low, and consists, in great part at least, of layers of clay or loose earth. Nordenskiöld either took this last description from the earlier, unreliable maps, or possibly allowed himself to be misled by the fog which beset them during their voyage in these waters.

In the evening we were approaching the north end of the land, but the current, which we had had with us earlier in the day, was now against us, and it seemed as if we were never to get past an island that lay off the shore to the north of us. The mountain height which I had seen at an earlier hour through the telescope lay here some way inland. It was flat on the top, with precipitous sides, like those mountains last described. It seemed to be sandstone or basaltic rock; only the horizontal strata of the ledges on its sides were not visible. I calculated its height at 1000 to 1500 feet. Out at sea we saw several new islands, the nearest of them being of some size.

The moment seemed to be at hand when we were at last to round that point which had haunted us for so long—the second of the greatest difficulties I expected to have to overcome on this expedition. I sat up in the crow’s-nest in the evening, looking out to the north. The land was low and desolate. The sun had long since gone down behind the sea, and the dreamy evening sky was yellow and gold. It was lonely and still up here, high above the water. Only one star was to be seen. It stood straight above Cape Chelyuskin, shining clearly and sadly in the pale sky. As we sailed on and got the cape more to the east of us the star went with it; it was always there, straight above. I could not help sitting watching it. It seemed to have some charm for me, and to bring such peace. Was it my star? Was it the spirit of home following and smiling to me now? Many a thought it brought to me as the Fram toiled on through the melancholy night, past the northernmost point of the old world.

Towards morning we were off what we took to be actually the northern extremity. We stood in near land, and at the change of the watch, exactly at 4 o’clock, our flags were hoisted, and our three last cartridges sent a thundering salute over the sea. Almost at the same moment the sun rose. Then our poetic doctor burst forth into the following touching lines:

“Up go the flags, off goes the gun;

The clock strikes four—and lo, the sun!”

As the sun rose, the Chelyuskin troll, that had so long had us in his power, was banned. We had escaped the danger of a winter’s imprisonment on this coast, and we saw the way clear to our goal—the drift-ice to the north of the New Siberian Islands. In honor of the occasion all hands were turned out, and punch, fruit, and cigars were served in the festally lighted saloon. Something special in the way of a toast was expected on such an occasion. I lifted my glass, and made the following speech: “Skoal, my lads, and be glad we’ve passed Chelyuskin!” Then there was some organ-playing, during which I went up into the crow’s-nest again, to have a last look at the land. I now saw that the height I had noticed in the evening, which has already been described, lies on the west side of the peninsula, while farther east a lower and more rounded height stretches southward. This last must be the one mentioned by Nordenskiöld, and, according to his description, the real north point must lie out beyond it; so that we were now off King Oscar’s Bay; but I looked in vain through the telescope for Nordenskiöld’s cairn. I had the greatest inclination to land, but did not think that we could spare the time. The bay, which was clear of ice at the time of the Vega’s visit, was now closed in with thick winter ice, frozen fast to the land.

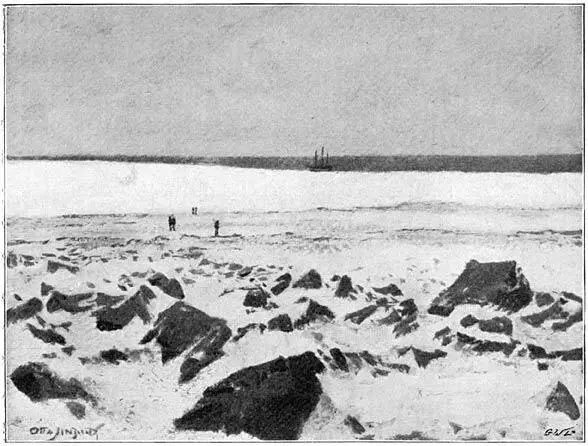

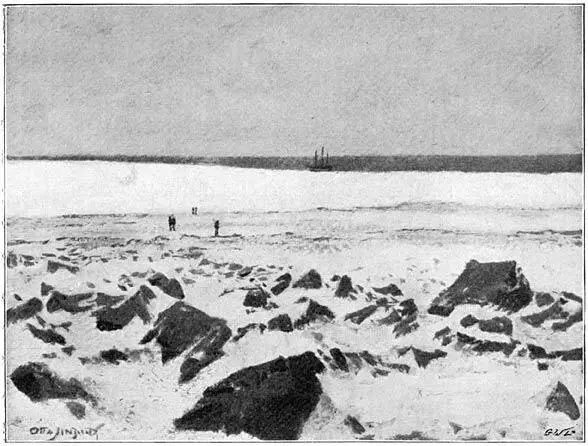

Cape Chelyuskin, the Northernmost point of the Old World

We had an open channel before us; but we could see the edge of the drift-ice out at sea. A little farther west we passed a couple of small islands, lying a short way from the coast. We had to stop before noon at the northwestern corner of Chelyuskin, on account of the drift-ice which seemed to reach right into the land before us. To judge by the dark air, there was open water again on the other side of an island which lay ahead. We landed and made sure that some straits or fjords on the inside of this island, to the south, were quite closed with firm ice; and in the evening the Fram forced her way through the drift-ice on the outside of it. We steamed and sailed southward along the coast all night, making splendid way; when the wind was blowing stiffest we went at the rate of 9 knots. We came upon ice every now and then, but got through it easily.

On land east of Cape Chelyuskin (September 10, 1893)

( By Otto Sinding, from a Photograph )

Towards morning (September 11th) we had high land ahead, and had to change our course to due east, keeping to this all day. When I came on deck before noon I saw a fine tract of hill country, with high summits and valleys between. It was the first view of the sort since we had left Vardö, and, after the monotonous low land we had been coasting along for months, it was refreshing to see such mountains again. They ended with a precipitous descent to the east, and eastward from that extended a perfectly flat plain. In the course of the day we quite lost sight of land, and strangely enough did not see it again; nor did we see the Islands of St. Peter and St. Paul, though, according to the maps, our course lay close past them.

Plate I.

Walruses Killed off the East Coast of the Taimyr Peninsula, 12th September 1893. Water-Colour Sketch.

Thursday, September 12th. Henriksen awoke me this morning at 6 with the information that there were several walruses lying on a floe quite close to us. “By Jove!” Up I jumped and had my clothes on in a trice. It was a lovely morning—fine, still weather; the walruses’ guffaw sounded over to us along the clear ice surface. They were lying crowded together on a floe a little to landward from us, blue mountains glittering behind them in the sun. At last the harpoons were sharpened, guns and cartridges ready, and Henriksen, Juell, and I set off. There seemed to be a slight breeze from the south, so we rowed to the north side of the floe, to get to leeward of the animals. From time to time their sentry raised his head, but apparently did not see us. We advanced slowly, and soon we were so near that we had to row very cautiously. Juell kept us going, while Henriksen was ready in the bow with a harpoon, and I behind him with a gun. The moment the sentry raised his head the oars stopped, and we stood motionless; when he sunk it again, a few more strokes brought us nearer.

Body to body they lay close-packed on a small floe, old and young ones mixed. Enormous masses of flesh they were! Now and again one of the ladies fanned herself by moving one of her flappers backward and forward over her body; then she lay quiet again on her back or side. “Good gracious! what a lot of meat!” said Juell, who was cook. More and more cautiously we drew near. While I sat ready with the gun, Henriksen took a good grip of the harpoon shaft, and as the boat touched the floe he rose, and off flew the harpoon. But it struck too high, glanced off the tough hide, and skipped over the backs of the animals. Now there was a pretty to do! Ten or twelve great weird faces glared upon us at once; the colossal creatures twisted themselves round with incredible celerity, and came waddling with lifted heads and hollow bellowings to the edge of the ice where we lay. It was undeniably an imposing sight; but I laid my gun to my shoulder and fired at one of the biggest heads. The animal staggered, and then fell head foremost into the water. Now a ball into another head; this creature fell too, but was able to fling itself into the sea. And now the whole herd dashed in, and we as well as they were hidden in spray. It had all happened in a few seconds. But up they came again immediately round the boat, the one head bigger and uglier than the other, their young ones close beside them. They stood up in the water, bellowed and roared till the air trembled, threw themselves forward towards us, then rose up again, and new bellowings filled the air. Then they rolled over and disappeared with a splash, then bobbed up again. The water foamed and boiled for yards around—the ice-world that had been so still before seemed in a moment to have been transformed into a raging bedlam. Any moment we might expect to have a walrus tusk or two through the boat, or to be heaved up and capsized. Something of this kind was the very least that could happen after such a terrible commotion. But the hurly-burly went on and nothing came of it. I again picked out my victims. They went on bellowing and grunting like the others, but with blood streaming from their mouths and noses. Another ball, and one tumbled over and floated on the water; now a ball to the second, and it did the same. Henriksen was ready with the harpoons, and secured them both. One more was shot; but we had no more harpoons, and had to strike a seal-hook into it to hold it up. The hook slipped, however, and the animal sank before we could save it. While we were towing our booty to an ice-floe we were still, for part of the time at least, surrounded by walruses; but there was no use in shooting any more, for we had no means of carrying them off. The Fram presently came up and took our two on board, and we were soon going ahead along the coast. We saw many walruses in this part. We shot two others in the afternoon, and could have got many more if we had had time to spare. It was in this same neighborhood that Nordenskiöld also saw one or two small herds.

Читать дальше