“Wednesday, September 20th. I have had a rough awakening from my dream. As I was sitting at 11 A.m., looking at the map and thinking that my cup would soon be full—we had almost reached 78°—there was a sudden luff, and I rushed out. Ahead of us lay the edge of the ice, long and compact, shining through the fog. I had a strong inclination to go eastward, on the possibility of there being land in that direction; but it looked as if the ice extended farther south there, and there was the probability of being able to reach a higher latitude if we kept west; so we headed that way. The sun broke through for a moment just now, so we took an observation, which showed us to be in about 77° 44′ north latitude.”

We now held northwest along the edge of the ice. It seemed to me as if there might be land at no great distance, we saw such a remarkable number of birds of various kinds. A flock of snipe or wading birds met us, followed us for a time, and then took their way south. They were probably on their passage from some land to the north of us. We could see nothing, as the fog lay persistently over the ice. Again, later, we saw flocks of small snipe, indicating the possible proximity of land. Next day the weather was clearer, but still there was no land in sight. We were now a good way north of the spot where Baron von Toll has mapped the south coast of Sannikoff Land, but in about the same longitude. So it is probably only a small island, and in any case cannot extend far north.

On September 21st we had thick fog again, and when we had sailed north to the head of a bay in the ice, and could get no farther, I decided to wait here for clear weather to see if progress farther north were possible. I calculated that we were now in about 78½° north latitude. We tried several times during the day to take soundings, but did not succeed in reaching the bottom with 215 fathoms of line.

“To-day made the agreeable discovery that there are bugs on board. Must plan a campaign against them.

“Friday, September 22d. Brilliant sunshine once again, and white dazzling ice ahead. First we lay still in the fog because we could not see which way to go; now it is clear, and we know just as little about it. It looks as if we were at the northern boundary of the open water. To the west the ice appears to extend south again. To the north it is compact and white—only a small open rift or pool every here and there; and the sky is whitish-blue everywhere on the horizon. It is from the east we have just come, but there we could see very little; and for want of anything better to do we shall make a short excursion in that direction, on the possibility of finding openings in the ice. If there were only time, what I should like would be to go east as far as Sannikoff Island, or, better still, all the way to Bennet Land, to see what condition things are in there; but it is too late now. The sea will soon be freezing, and we should run a great risk of being frozen in at a disadvantageous point.”

Earlier Arctic explorers have considered it a necessity to keep near some coast. But this was exactly what I wanted to avoid. It was the drift of the ice that I wished to get into, and what I most feared was being blocked by land. It seemed as if we might do much worse than give ourselves up to the ice where we were—especially as our excursion to the east had proved that following the ice-edge in that direction would soon force us south again. So in the meantime we made fast to a great ice-block, and prepared to clean the boiler and shift coals. “We are lying in open water, with only a few large floes here and there; but I have a presentiment that this is our winter harbor.

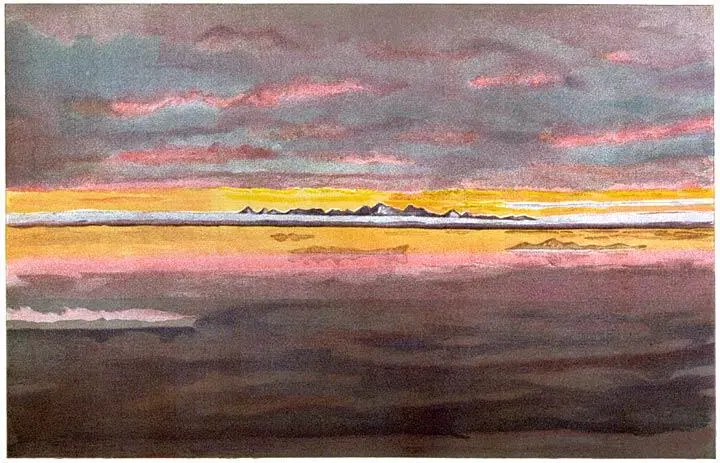

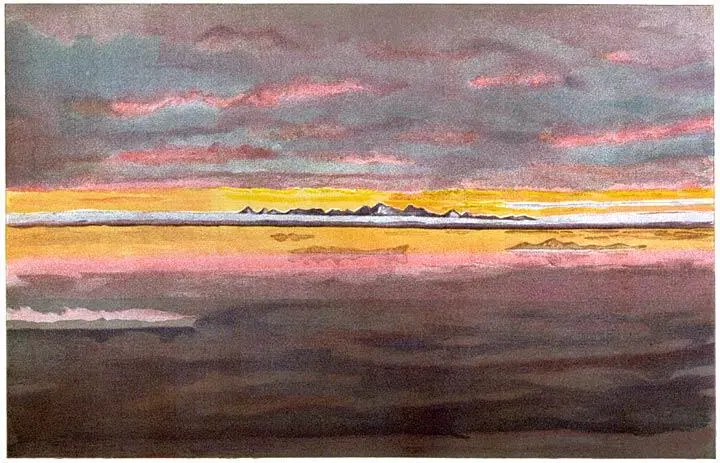

Plate III.

Sunset off the the North Coast of Asia, North of the Mouth of the Chatanga, 12th September 1893. Water-Colour Sketch.

“Great bug war to-day. We play the big steam hose on mattresses, sofa-cushions—everything that we think can possibly harbor the enemies. All clothes are put into a barrel, which is hermetically closed, except where the hose is introduced. Then full steam is set on. It whizzes and whistles inside, and a little forces its way through the joints, and we think that the animals must be having a fine hot time of it. But suddenly the barrel cracks, the steam rushes out, and the lid bursts off with a violent explosion, and is flung far along the deck. I still hope that there has been a great slaughter, for these are horrible enemies. Juell tried the old experiment of setting one on a piece of wood to see if it would creep north. It would not move at all, so he took a blubber hook and hit it to make it go; but it would do nothing but wriggle its head—the harder he hit the more it wriggled. ‘Squash it, then,’ said Bentzen. And squashed it was.

“Friday, September 23d. We are still at the same moorings, working at the coal. An unpleasant contrast—everything on board, men and dogs included, black and filthy, and everything around white and bright in beautiful sunshine. It looks as if more ice were driving in.

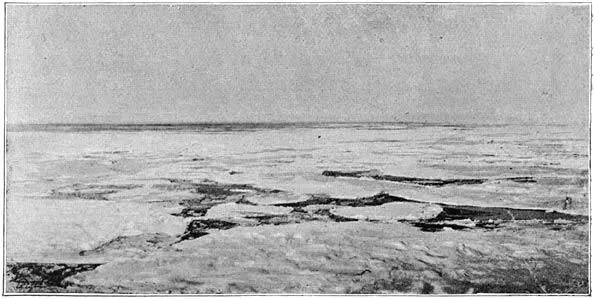

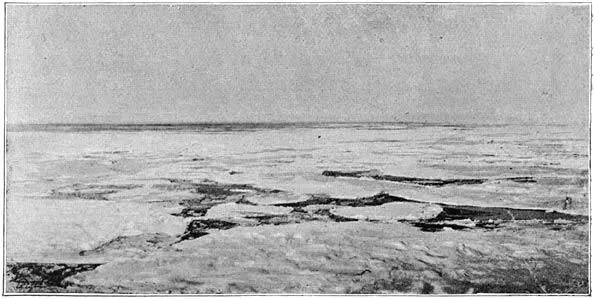

The ice into which the “Fram” was frozen (September 25, 1893)

( From a Photograph )

“Sunday, September 24th. Still coal-shifting. Fog in the morning, which cleared off as the day went on, when we discovered that we were closely surrounded on all sides by tolerably thick ice. Between the floes lies slush-ice, which will soon be quite firm. There is an open pool to be seen to the north, but not a large one. From the crow’s-nest, with the telescope, we can still descry the sea across the ice to the south. It looks as if we were being shut in. Well, we must e’en bid the ice welcome. A dead region this; no life in any direction, except a single seal ( Phoca fœtida ) in the water; and on the floe beside us we can see a bear-track some days old. We again try to get soundings, but still find no bottom; it is remarkable that there should be such depth here.”

Ugh! one can hardly imagine a dirtier, nastier job than a spell of coal-shifting on board. It is a pity that such a useful thing as coal should be so black! What we are doing now is only hoisting it from the hold and filling the bunkers with it; but every man on board must help, and everything is in a mess. So many men must stand on the coal-heap in the hold and fill the buckets, and so many hoist them. Jacobsen is specially good at this last job; his strong arms pull up bucket after bucket as if they were as many boxes of matches. The rest of us go backward and forward with the buckets between the main-hatch and the half-deck, pouring the coal into the bunkers; and down below stands Amundsen packing it, as black as he can be. Of course coal-dust is flying over the whole deck; the dogs creep into corners, black and toussled; and we ourselves—well, we don’t wear our best clothes on such days. We got some amusement out of the remarkable appearance of our faces, with their dark complexions, black streaks at the most unlikely places, and eyes and white teeth shining through the dirt. Any one happening to touch the white wall below with his hand leaves a black five-fingered blot; and the doors have a wealth of such mementos. The seats of the sofas must have their wrong sides turned up, else they would bear lasting marks of another part of the body; and the table-cloth—well, we fortunately do not possess such a thing. In short, coal-shifting is as dirty and wretched an experience as one can well imagine in these bright and pure surroundings. One good thing is that there is plenty of fresh water to wash with; we can find it in every hollow on the floes, so there is some hope of our being clean again in time, and it is possible that this may be our last coal-shifting.

Читать дальше