Nor were we successful in finding Hovgaard’s Islands as we sailed north. When I supposed that we were off them, just on the north side of the entrance to Taimur Strait, I saw, to my surprise, a high mountain almost directly north of us, which seemed as if it must be on the mainland. What could be the explanation of this? I began to have a growing suspicion that this was a regular labyrinth of islands we had got into. We were hoping to investigate and clear up the matter when thick weather, with sleet and rain, most inconveniently came on, and we had to leave this problem for the future to solve.

The mist was thick, and soon the darkness of night was added to it, so that we could not see land at any great distance. It might seem rather risky to push ahead now, but it was an opportunity not to be lost. We slackened speed a little, and kept on along the coast all night, in readiness to turn as soon as land was observed ahead. Satisfied that things were in good hands, as it was Sverdrup’s watch, I lay down in my berth with a lighter mind than I had had for long.

At 6 o’clock next morning (September 7th) Sverdrup roused me with the information that we had passed Taimur Island, or Cape Lapteff, at 3 A.M., and were now at Taimur Bay, but with close ice and an island ahead. It was possible that we might reach the island, as a channel had just opened through the ice in that direction; but we were at present in a tearing “whirlpool” current, and should be obliged to put back for the moment. After breakfast I went up into the crow’s-nest. It was brilliant sunshine. I found that Sverdrup’s island must be mainland, which, however, stretched remarkably far west compared with that given on the maps. I could still see Taimur Island behind me, and the most easterly of Almquist’s Islands lay gleaming in the sun to the north. It was a long, sandy point that we had ahead, and I could follow the land in a southerly direction till it disappeared on the horizon at the head of the bay in the south. Then there was a small strip where no land, only open water, could be made out. After that the land emerged on the west side of the bay, stretching towards Taimur Island. With its heights and round knolls this land was essentially different from the low coast on the east side of the bay.

To the north of the point ahead of us I saw open water; there was some ice between us and it, but the Fram forced her way through. When we got out, right off the point, I was surprised to notice the sea suddenly covered with brown, clayey water. It could not be a deep layer, for the track we left behind was quite clear. The clayey water seemed to be skimmed to either side by the passage of the ship. I ordered soundings to be taken, and found, as I expected, shallower water—first 8 fathoms, then 6½, then 5½. I stopped now, and backed. Things looked very suspicious, and round us ice-floes lay stranded. There was also a very strong current running northeast. Constantly sounding, we again went slowly forward. Fortunately the lead went on showing 5 fathoms. Presently we got into deeper water—6 fathoms, then 6½—and now we went on at full speed again. We were soon out into the clear, blue water on the other side. There was quite a sharp boundary-line between the brown surface water and the clear blue. The muddy water evidently came from some river a little farther south.

From this point the land trended back in an easterly direction, and we held east and northeast in the open water between it and the ice. In the afternoon this channel grew very narrow, and we got right under the coast, where it again slopes north. We kept close along it in a very narrow cut, with a depth of 6 to 8 fathoms, but in the evening had to stop, as the ice lay packed close in to the shore ahead of us.

This land we had been coasting along bore a strong resemblance to Yalmal. The same low plains, rising very little above the sea, and not visible at any great distance. It was perhaps rather more undulating. At one or two places I even saw some ridges of a certain elevation a little way inland. The shore the whole way seemed to be formed of strata of sand and clay, the margin sloping steeply to the sea.

Many reindeer herds were to be seen on the plains, and next morning (September 8th) I went on shore on a hunting expedition. Having shot one reindeer I was on my way farther inland in search of more, when I made a surprising discovery, which attracted all my attention and made me quite forget the errand I had come on. It was a large fjord cutting its way in through the land to the north of me. I went as far as possible to find out all I could about it, but did not manage to see the end of it. So far as I could see, it was a fine broad sheet of water, stretching eastward to some blue mountains far, far inland, which, at the extreme limit of my vision, seemed to slope down to the water. Beyond them I could distinguish nothing. My imagination was fired, and for a moment it seemed to me as if this might almost be a strait, stretching right across the land here, and making an island of the Chelyuskin Peninsula. But probably it was only a river, which widened out near its mouth into a broad lake, as several of the Siberian rivers do. All about the clay plains I was tramping over, enormous erratic blocks, of various formations, lay scattered. They can only have been brought here by the great glaciers of the Ice Age. There was not much life to be seen. Besides reindeer there were just a few willow-grouse, snow-buntings, and snipe; and I saw tracks of foxes and lemmings. This farthest north part of Siberia is quite uninhabited, and has probably not been visited even by the wandering nomads. However, I saw a circular moss-heap on a plain far inland, which looked as if it might be the work of man’s hand. Perhaps, after all, some Samoyede had been here collecting moss for his reindeer; but it must have been long ago; for the moss looked quite black and rotten. The heap was quite possibly only one of Nature’s freaks—she is often capricious.

What a constant alternation of light and shadow there is in this Arctic land. When I went up to the crow’s-nest next morning (September 9th) I saw that the ice to the north had loosened from the land, and I could trace a channel which might lead us northward into open water. I at once gave the order to get up steam. The barometer was certainly low—lower than we had ever had it yet; it was down to 733 mm.—the wind was blowing in heavy squalls off the land, and in on the plains the gusts were whirling up clouds of sand and dust.

Sverdrup thought it would be safer to stay where we were; but it would be too annoying to miss this splendid opportunity; and the sunshine was so beautiful, and the sky so smiling and reassuring. I gave orders to set sail, and soon we were pushing on northward through the ice, under steam, and with every stitch of canvas that we could crowd on. Cape Chelyuskin must be vanquished! Never had the Fram gone so fast; she made more than 8 knots by the log; it seemed as though she knew how much depended on her getting on. Soon we were through the ice, and had open water along the land as far as the eye could reach. We passed point after point, discovering new fjords and islands on the way, and soon I thought that I caught a glimpse through the large telescope of some mountains far away north; they must be in the neighborhood of Cape Chelyuskin itself.

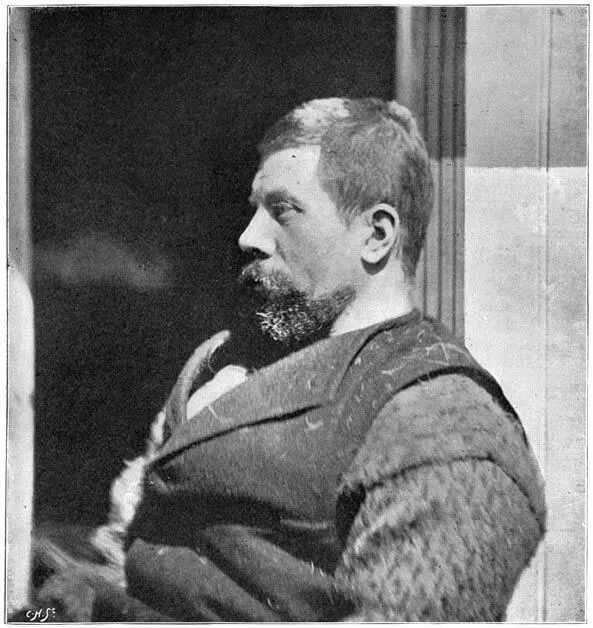

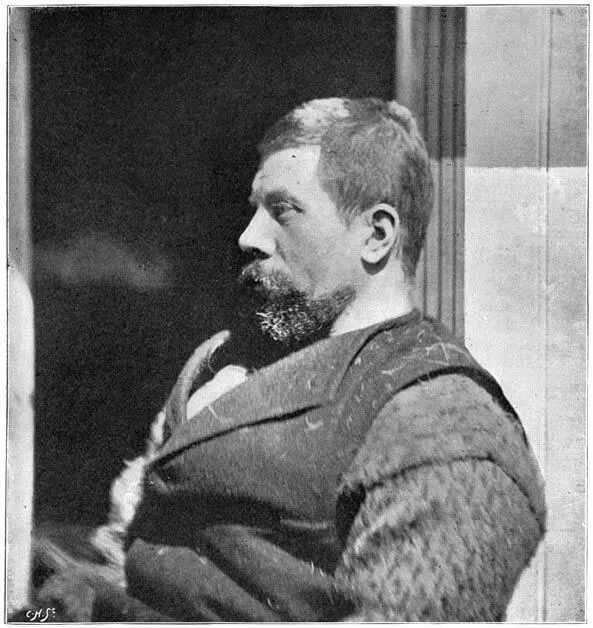

Anton Amundsen

( From a photograph taken in December, 1893 )

The land along which we to-day coasted to the northward was quite low, some of it like what I had seen on shore the previous day. At some distance from the low coast, fairly high mountains or mountain chains were to be seen. Some of them seemed to consist of horizontal sedimentary schist; they were flat-topped, with precipitous sides. Farther inland the mountains were all white with snow. At one point it seemed as if the whole range were covered with a sheet of ice, or great snow-field that spread itself down the sides. At the edge of this sheet I could see projecting masses of rock, but all the inner part was spotless white. It seemed almost too continuous and even to be new snow, and looked like a permanent snow mantle.

Читать дальше