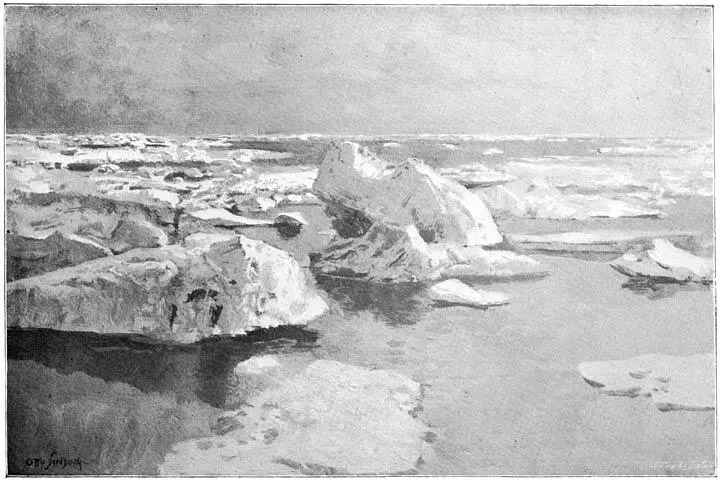

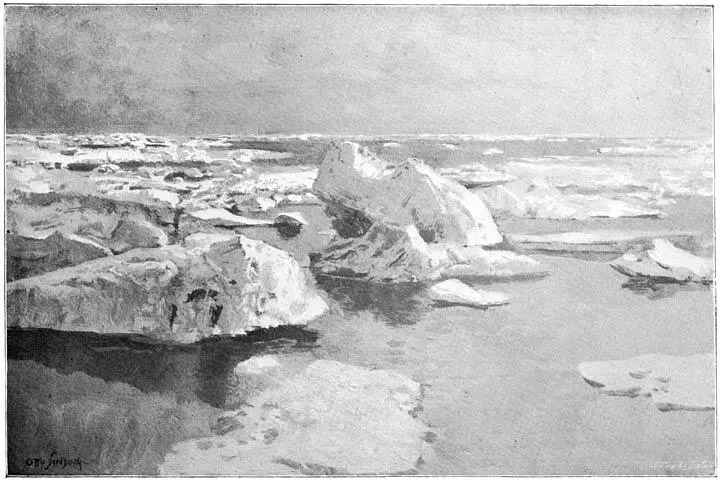

First drift-ice. July 28, 1893

( By Otto Sinding )

On the evening of July 27th, while still fog-bound, we quite unexpectedly met with ice; a mere strip, indeed, which we easily passed through, but it boded ill. In the night we met with more—a broader strip this time, which also we passed through. But next morning I was called up with the information that there was thick, old ice ahead. Well, if ice difficulties were to begin so soon, it would be a bad lookout indeed. Such are the chill surprises that the Arctic Sea has more than enough of. I dressed and was up in the crow’s-nest in a twinkling. The ice lay extended everywhere, as far as the eye could reach through the fog, which had lifted a little. There was no small quantity of ice, but it was tolerably open, and there was nothing for it but to be true to our watchword and “gå fram”—push onward. For a good while we picked our way. But now it began to lie closer, with large floes every here and there, and at the same time the fog grew denser, and we could not see our way at all. To go ahead in difficult ice and in a fog is not very prudent, for it is impossible to tell just where you are going, and you are apt to be set fast before you know where you are. So we had to stop and wait. But still the fog grew ever denser, while the ice did the same. Our hopes meanwhile rose and fell, but mostly the latter, I think. To encounter so much ice already in these waters, where at this time of year the sea is, as a rule, quite free from it, boded anything but good. Already at Tromsö and Vardö we had heard bad news; the White Sea, they said, had only been clear of ice a very short time, and a boat that had tried to reach Yugor Strait had had to turn back because of the ice. Neither were our anticipations of the Kara Sea altogether cheerful. What might we not expect there? For the Urania , with our coals, too, this ice was a bad business; for it would be unable to make its way through unless it had found navigable water farther south along the Russian coast.

Just as our prospects were at their darkest, and we were preparing to seek a way back out of the ice, which kept getting ever denser, the joyful tidings came that the fog was lifting, and that clear water was visible ahead to the east on the other side of the ice. After forcing our way ahead for some hours between the heavy floes, we were once more in open water. This first bout with the ice, however, showed us plainly what an excellent ice-boat the Fram was. It was a royal pleasure to work her ahead through difficult ice. She twisted and turned “like a ball on a platter.” No channel between the floes so winding and awkward but she could get through it. But it is hard work for the helmsman. “Hard astarboard! Hard aport! Steady! Hard astarboard again!” goes on incessantly without so much as a breathing-space. And he rattles the wheel round, the sweat pours off him, and round it goes again like a spinning-wheel. And the ship swings round and wriggles her way forward among the floes without touching, if there is only just an opening wide enough for her to slip through; and where there is none she drives full tilt at the ice, with her heavy plunge, runs her sloping bows up on it, treads it under her, and bursts the floes asunder. And how strong she is too! Even when she goes full speed at a floe, not a creak, not a sound, is to be heard in her; if she gives a little shake it is all she does.

On Saturday, July 29th, we again headed eastward towards Yugor Strait as fast as sails and steam could take us. We had open sea ahead, the weather was fine and the wind fair. Next morning we came under the south side of Dolgoi or Langöia, as the Norwegian whalers call it, where we had to stand to the northward. On reaching the north of the island we again bore eastward. Here I descried from the crow’s-nest, as far as I could make out, several islands which are not given on the charts. They lay a little to the east of Langöia.

It was now pretty clear that the Urania had not made her way through the ice. While we were sitting in the saloon in the forenoon, talking about it, a cry was heard from deck that the sloop was in sight. It was joyful news, but the joy was of no long duration. The next moment we heard she had a crow’s-nest on her mast, so she was doubtless a sealer. When she sighted us she bore off to the south, probably fearing that we were a Russian war-ship or something equally bad. So, as we had no particular interest in her, we let her go on her way in peace.

Later in the day we neared Yugor Strait. We kept a sharp lookout for land ahead, but none could be seen. Hour after hour passed as we glided onward at good speed, but still no land. Certainly it would not be high land, but nevertheless this was strange. Yes—there it lies, like a low shadow over the horizon, on the port bow. It is land—it is Vaigats Island. Soon we sight more of it—abaft the beam; then, too, the mainland on the south side of the strait. More and more of it comes in sight—it increases rapidly. All low and level land, no heights, no variety, no apparent opening for the strait ahead. Thence it stretches away to the north and south in a soft low curve. This is the threshold of Asia’s boundless plains, so different from all we have been used to.

We now glided into the strait, with its low rocky shores on either side. The strata of the rocks lie endways, and are crumpled and broken, but on the surface everything is level and smooth. No one who travels over the flat green plains and tundras would have any idea of the mysteries and upheavals that lie hidden beneath the sward. Here once upon a time were mountains and valleys, now all worn away and washed out.

We looked out for Khabarova. On the north side of the sound there was a mark; a shipwrecked sloop lay on the shore; it was a Norwegian sealer. The wreck of a smaller vessel lay by its side. On the south side was a flag-staff, and on it a red flag; Khabarova must then lie behind it. At last one or two buildings or shanties appeared behind a promontory, and soon the whole place lay exposed to view, consisting of tents and a few houses. On a little jutting-out point close by us was a large red building, with white door-frames, of a very homelike appearance. It was indeed a Norwegian warehouse which Sibiriakoff had imported from Finmarken. But here the water was shallow, and we had to proceed carefully for fear of running aground. We kept heaving the lead incessantly—we had 5 fathoms of water, and then 4, then not much more than we needed, and then it shelved to a little over 3 fathoms. This was rather too close work, so we stood out again a bit to wait till we got a little nearer the place before drawing in to the shore.

A boat was now seen slowly approaching from the land. A man of middle height, with an open, kindly face and reddish beard, came on board. He might have been a Norwegian from his appearance. I went to meet him, and asked him in German if he was Trontheim. Yes, he was. After him there came a number of strange figures clad in heavy robes of reindeer-skin, which nearly touched the deck. On their heads they wore peculiar “bashlyk”-like caps of reincalf-skin, beneath which strongly marked bearded faces showed forth, such as might well have belonged to old Norwegian Vikings. The whole scene, indeed, called up in my mind a picture of the Viking Age, of expeditions to Gardarike and Bjarmeland. They were fine, stalwart-looking fellows, these Russian traders, who barter with the natives, giving them brandy in exchange for bearskins, sealskins, and other valuables, and who, when once they have a hold on a man, keep him in such a state of dependence that he can scarcely call his soul his own. “Es ist eine alte Geschichte, doch wird sie immer neu.” Soon, too, the Samoyedes came flocking on board, pleasant-featured people of the broad Asiatic type. Of course it was only the men who came.

Читать дальше