We had kept along the Vaigats shore, but now crossed over towards the south side of the strait. When about the middle of the channel I was startled by all at once seeing the bottom grow light under us, and had nearly run the boat on a shoal of which no one knew anything. There was scarcely more than two or three feet of water, and the current ran over it like a rapid river. Shoals and sunken rocks abound there on every hand, especially on the south side of the strait, and it required great care to navigate a vessel through it. Near the eastern mouth of the strait we put into a little creek, dragged the boat up on the beach, and then, taking our guns, made for some high-lying land we had noticed. We tramped along over the same undulating plain-land with low ridges, as we had seen everywhere round the Yugor Strait. A brownish-green carpet of moss and grass spread over the plain, bestrewn with flowers of rare beauty. During the long, cold Siberian winter the snow lies in a thick mass over the tundra; but no sooner does the sun get the better of it than hosts of tiny northern flowers burst their way up through the fast-disappearing coating of snow and open their modest calices, blushing in the radiant summer day that bathes the plain in its splendor. Saxifrages with large blooms, pale-yellow mountain poppies ( Papaver nudicaule ) stand in bright clusters, and here and there with bluish forget-me-nots and white cloud-berry flowers; in some boggy hollows the cotton-grass spreads its wavy down carpet, while in other spots small forests of bluebells softly tingle in the wind on their upright stalks. These flowers are not at all brilliant specimens, being in most cases not more than a couple of inches high, but they are all the more exquisite on that account, and in such surroundings their beauty is singularly attractive. While the eye vainly seeks for a resting-place over the boundless plain, these modest blooms smile at you and take the fancy captive.

And over these mighty tundra-plains of Asia, stretching infinitely onward from one sky-line to the other, the nomad wanders with his reindeer herds, a glorious, free life! Where he wills he pitches his tent, his reindeer around him; and at his will again he goes on his way. I almost envied him. He has no goal to struggle towards, no anxieties to endure—he has merely to live! I wellnigh wished that I could live his peaceful life, with wife and child, on these boundless, open plains, unfettered, happy.

After we had proceeded a short distance, we became aware of a white object sitting on a stone heap beneath a little ridge, and soon noticed more in other directions. They looked quite ghostly as they sat there silent and motionless. With the help of my field-glass I discovered that they were snow-owls. We set out after them, but they took care to keep out of the range of a fowling-piece. Sverdrup, however, shot one or two with his rifle. There was a great number of them; I could count as many as eight or ten at once. They sat motionless on tussocks of grass or stones, watching, no doubt, for lemmings, of which, judging from their tracks, there must have been quantities. We, however, did not see any.

From the tops of the ridges we could see over the Kara Sea to the northeast. Everywhere ice could be descried through the telescope, far on the horizon—ice, too, that seemed tolerably close and massive. But between it and the coast there was open water, stretching, like a wide channel, as far as the eye could reach to the southeast. This was all we could make out, but it was in reality all we wanted. There seemed to be no doubt that we could make our way forward, and, well satisfied, we returned to our boat. Here we lighted a fire of driftwood, and made some glorious coffee.

As the coffee-kettle was singing over a splendid fire, and we stretched ourselves at full length on the slope by its side and smoked a quiet pipe, Sverdrup made himself thoroughly comfortable, and told us one story after another. However gloomy a country might look, however desolate, if only there were plenty of driftwood on the beach, so that one could make a right good fire, the bigger the better, then his eyes would glisten with delight—that land was his El Dorado. So from that time forth he conceived a high opinion of the Siberian coast—a right good place for wintering, he called it.

On our way back we ran at full speed on to a sunken rock. After a bump or two the boat slid over it; but just as she was slipping off on the other side the propeller struck on the rock, so that the stern gave a bound into the air while the engine whizzed round at a tearing rate. It all happened in a second, before I had time to stop her. Unluckily one screw blade was broken off, but we drove ahead with the other as best we could. Our progress was certainly rather uneven, but for all that we managed to get on somehow.

Towards morning we drew near the Fram , passing two Samoyedes, who had drawn their boat up on an ice-floe and were looking out for seals. I wonder what they thought when they saw our tiny boat shoot by them without steam, sails, or oars. We, at all events, looked down on these “poor savages” with the self-satisfied compassion of Europeans, as, comfortably seated, we dashed past them.

But pride comes before a fall! We had not gone far when—whir, whir, whir—a fearful racket! bits of broken steel springs whizzed past my ears, and the whole machine came to a dead stop. It was not to be moved either forward or backward. The vibration of the one-bladed propeller had brought the lead line little by little within the range of the fly-wheel, and all at once the whole line was drawn into the machinery, and got so dreadfully entangled in it that we had to take the whole thing to pieces to get it clear once more. So we had to endure the humiliation of rowing back to our proud ship, for whose flesh-pots we had long been anhungered.

The net result of the day was: tolerably good news about the Kara Sea; forty birds, principally geese and long-tailed ducks; one seal; and a disabled boat. Amundsen and I, however, soon put this in complete repair again—but in so doing I fear I forfeited forever and a day the esteem of the Russians and Samoyedes in these parts. Some of them had been on board in the morning and seen me hard at work in the boat in my shirt-sleeves, face and bare arms dirty with oil and other messes. They went on shore afterwards to Trontheim, and said that I could not possibly be a great person, slaving away like any other workman on board, and looking worse than a common rough. Trontheim, unfortunately, knew of nothing that could be said in my excuse; there is no fighting against facts.

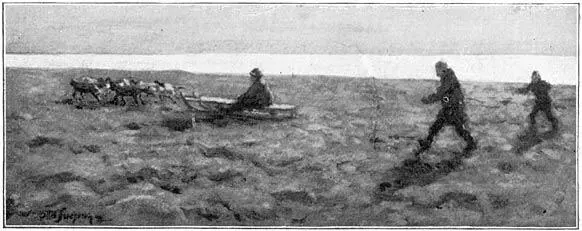

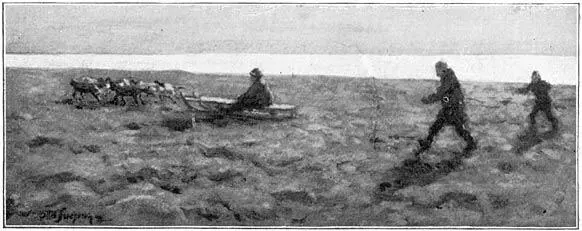

In the evening some of us went on shore to try the dogs. Trontheim picked out ten of them and harnessed them to a Samoyede sledge. No sooner were we ready and I had taken my seat than the team caught sight of a wretched strange dog that had come near, and off dashed dogs, sledge, and my valuable person after the poor creature. There was a tremendous uproar; all the ten tumbled over each other like wild wolves, biting and tearing wherever they could catch hold; blood ran in streams, and the culprit howled pitiably, while Trontheim tore round like a madman, striking right and left with his long switch. Samoyedes and Russians came screaming from all sides. I sat passively on the sledge in the middle of it all, dumb with fright, and it was ever so long before it occurred to me that there was perhaps something for me too to do. With a horrible yell I flung myself on some of the worst fighters, got hold of them by the neck, and managed to give the culprit time to get away.

Our trial trip with the dogs

Читать дальше