The first question I asked Trontheim was about the ice. He replied that Yugor Strait had been open a long while, and that he had been expecting our arrival every day since then with ever-increasing anxiety. The natives and the Russians had begun to jeer at him as time went on, and no Fram was to be seen; but now he had his revenge and was all sunshine. He thought the state of the ice in the Kara Sea would be favorable; some Samoyedes had said so, who had been seal-hunting near the eastern entrance of the Strait a day or two previously. This was not very much to build upon, certainly, but still sufficient to make us regret that we had not got there before. Then we spoke of the Urania , of which no one, of course, had seen anything. No ship had put in there for some time, except the sealing sloop we had passed in the morning.

Next we inquired about the dogs, and learned that everything was all right with them. To make sure, Trontheim had purchased forty dogs, though I had only asked for thirty. Five of these, from various mishaps, had died during their journey—one had been bitten to death, two had got hung fast and had been strangled while passing through a forest, etc., etc. One, moreover, had been taken ill a few days before, and was still on the sick list; but the remaining thirty-four were in good condition: we could hear them howling and barking. During this conversation we had come as near to Khabarova as we dared venture, and at seven in the evening cast anchor in about 3 fathoms of water.

Over the supper-table Trontheim told us his adventures. On the way from Sopva and Ural to the Pechora he heard that there was a dog epidemic in that locality; consequently he did not think it advisable to go to the Pechora as he had intended, but laid his course instead direct from Ural to Yugor Strait. Towards the end of the journey the snow had disappeared, and, in company with a reindeer caravan, he drove on with his dogs over the bare plain, stocks and stones and all, using the sledges none the less. The Samoyedes and natives of Northern Siberia have no vehicles but sledges. The summer sledge is somewhat higher than the winter sledge, in order that it may not hang fast upon stones and stumps. As may be supposed, however, summer sledging is anything but smooth work.

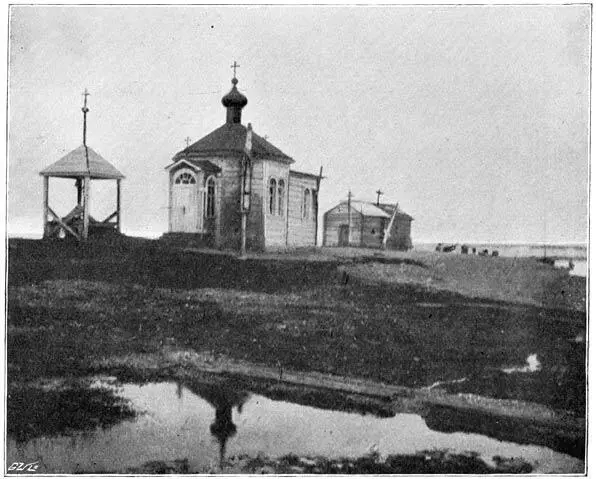

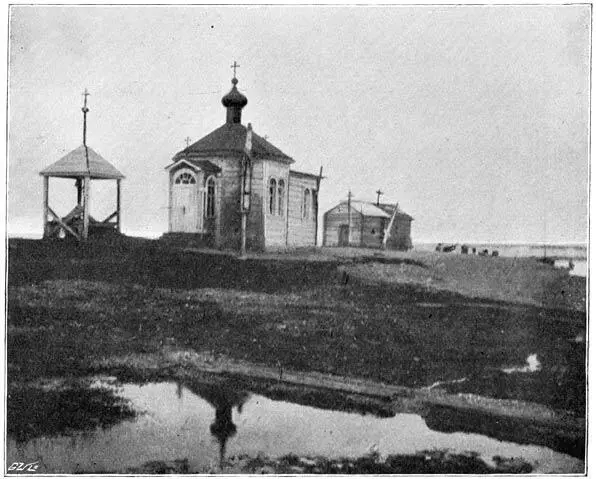

The new church and the old church at Khabarova

( From a Photograph )

After supper we went ashore, and were soon on the flat beach of Khabarova, the Russians and Samoyedes regarding us with the utmost curiosity. The first objects to attract our attention were the two churches—an old venerable-looking wooden shed, of an oblong rectangular form, and an octagonal pavilion, not unlike many summer-houses or garden pavilions that I have seen at home. How far the divergence between the two forms of religion was indicated in the two mathematical figures I am unable to say. It might be that the simplicity of the old faith was expressed in the simple, four-sided building, while the rites and ceremonies of the other were typified in the octagonal form, with its double number of corners to stumble against. Then we must go and see the monastery—“Skit,” as it was called—where the six monks had lived, or rather died, from what people said was scurvy, probably helped out by alcohol. It lay over against the new church, and resembled an ordinary low Russian timber-house. The priest and his assistants were living there now, and had asked Trontheim to take up his quarters with them. Trontheim, therefore, invited us in, and we soon found ourselves in a couple of comfortable log-built rooms with open fireplaces like our Norwegian “peis.”

After this we proceeded to the dog-camp, which was situated on a plain at some distance from the houses and tents. As we approached it the howling and barking kept getting worse and worse. When a short distance off we were surprised to see a Norwegian flag on the top of a pole. Trontheim’s face beamed with joy as our eyes fell on it. It was, he said, under the same flag as our expedition that his had been undertaken. There stood the dogs tied up, making a deafening clamor. Many of them appeared to be well-bred animals—long-haired, snow-white, with up-standing ears and pointed muzzles. With their gentle, good-natured looking faces they at once ingratiated themselves in our affections. Some of them more resembled a fox, and had shorter coats, while others were black or spotted. Evidently they were of different races, and some of them betrayed by their drooping ears a strong admixture of European blood. After having duly admired the ravenous way in which they swallowed raw fish (gwiniad), not without a good deal of snarling and wrangling, we took a walk inland to a lake close by in search of game; but we only found an Arctic gull with its brood. A channel had been dug from this lake to convey drinking-water to Khabarova. According to what Trontheim told us, this was the work of the monks—about the only work, probably, they had ever taken in hand. The soil here was a soft clay, and the channel was narrow and shallow, like a roadside ditch or gutter; the work could not have been very arduous. On the hill above the lake stood the flagstaff which we had noticed on our arrival. It had been erected by the excellent Trontheim to bid us welcome, and on the flag itself, as I afterwards discovered by chance, was the word “Vorwärts.” Trontheim had been told that was the name of our ship, so he was not a little disappointed when he came on board to find it was Fram instead. I consoled him, however, by telling him they both meant the same thing, and that his welcome was just as well meant, whether written in German or Norwegian. Trontheim told me afterwards that he was by descent a Norwegian, his father having been a ship’s captain from Trondhjem, and his mother an Esthonian, settled at Riga. His father had been much at sea, and had died early, so the son had not learnt Norwegian.

Peter Henriksen

( From a photograph taken in 1895 )

Naturally our first and foremost object was to learn all we could about the ice in the Arctic Sea. We had determined to push on as soon as possible; but we must have the boiler put in order first, while sundry pipes and valves in the engine wanted seeing to. As it would take several days to do this, Sverdrup, Peter Henriksen, and I set out next morning in our little petroleum launch to the eastern opening of the Yugor Strait, to see with our own eyes what might be the condition of the ice to the eastward. It was 28 miles thither. A quantity of ice was drifting through the strait from the east, and, as there was a northerly breeze, we at once turned our course northward to get under the lee of the north shore, where the water was more open. I had the rather thankless task of acting as helmsman and engineer at one and the same time. The boat went on like a little hero and made about six knots. Everything looked bright. But, alas! good fortune seldom lasts long, especially when one has to do with petroleum launches. A defect in the circulation-pump soon stopped the engine, and we could only go for short distances at a time, till we reached the north shore, where, after two hours’ hard work, I got the engines so far in order as to be able to continue our journey to the northeast through the sound between the drifting floes. We got on pretty well, except for an interruption every now and then when the engine took it into its head to come to a standstill. It caused a good deal of merriment when the stalwart Peter turned the crank to set her off again and the engine gave a start so as nearly to pull his arms out of joint and upset him head over heels in the boat. Every now and then a flock of long-tailed duck ( Harelda glacialis ) or other birds came whizzing by us, one or two of them invariably falling to our guns.

Читать дальше