4.These depots were arranged most carefully, and every precaution so well taken that we certainly should not have suffered from famine had we gone there. In the northernmost depot at Stan Durnova on the west coast of Kotelnoi, at 75° 37′ N. L., we should have found provisions for a week; with these we could easily have made our way 65 miles southward along the coast to the second depot at Urassalach, where, in a house built by Baron Von Toll in 1886, we should have found provisions for a whole month. Lastly, a third depot in a house on the south side of Little Liakhoff Island, with provisions for two months, would have enabled us to reach the mainland with ease.

Table of Contents

“So travel I north to the gloomy abode

That the sun never shines on—

There is no day.”

It was midsummer day. A dull, gloomy day; and with it came the inevitable leave-taking. The door closed behind me. For the last time I left my home and went alone down the garden to the beach, where the Fram’s little petroleum launch pitilessly awaited me. Behind me lay all I held dear in life. And what before me? How many years would pass ere I should see it all again? What would I not have given at that moment to be able to turn back; but up at the window little Liv was sitting clapping her hands. Happy child, little do you know what life is—how strangely mingled and how full of change. Like an arrow the little boat sped over Lysaker Bay, bearing me on the first stage of a journey on which life itself, if not more, was staked.

At last everything was in readiness. The hour had arrived towards which the persevering labor of years had been incessantly bent, and with it the feeling that, everything being provided and completed, responsibility might be thrown aside and the weary brain at last find rest. The Fram lies yonder at Pepperviken, impatiently panting and waiting for the signal, when the launch comes puffing past Dyna and runs alongside. The deck is closely packed with people come to bid a last farewell, and now all must leave the ship. Then the Fram weighs anchor, and, heavily laden and moving slowly, makes the tour of the little creek. The quays are black with crowds of people waving their hats and handkerchiefs. But silently and quietly the Fram heads towards the fjord, steers slowly past Bygdö and Dyna out on her unknown path, while little nimble craft, steamers, and pleasure-boats swarm around her. Peaceful and snug lay the villas along the shore behind their veils of foliage, just as they ever seemed of old. Ah, “fair is the woodland slope, and never did it look fairer!” Long, long, will it be before we shall plough these well-known waters again.

And now a last farewell to home. Yonder it lies on the point—the fjord sparkling in front, pine and fir woods around, a little smiling meadow-land and long wood-clad ridges behind. Through the glass one could descry a summer-clad figure by the bench under the fir-tree. …

It was the darkest hour of the whole journey.

And now out into the fjord. It was rainy weather, and a feeling of melancholy seemed to brood over the familiar landscape with all its memories.

It was not until noon next day (June 25th) that the Fram glided into the bay by Rækvik, Archer’s shipyard, near Laurvik, where her cradle stood, and where many a golden dream had been dreamt of her victorious career. Here we were to take the two long-boats on board and have them set up on their davits, and there were several other things to be shipped. It took the whole day and a good part of the next before all was completed. About three o’clock on the 26th we bade farewell to Rækvik and made a bend into Laurvik Bay, in order to stand out to sea by Frederiksværn. Archer himself had to take the wheel and steer his child this last bit before leaving the ship. And then came the farewell hand-shake; but few words were spoken, and they got into the boat, he, my brothers, and a friend, while the Fram glided ahead with her heavy motion, and the bonds that united us were severed. It was sad and strange to see this last relic of home in that little skiff on the wide blue surface, Anker’s cutter behind, and Laurvik farther in the distance. I almost think a tear glittered on that fine old face as he stood erect in the boat and shouted a farewell to us and to the Fram . Do you think he does not love the vessel? That he believes in her I know well. So we gave him the first salute from the Fram’s guns—a worthier inauguration they could not well have had.

Full speed ahead, and in the calm, bright summer weather, while the setting sun shed his beams over the land, the Fram stood out towards the blue sea, to get its first roll in the long, heaving swell. They stood up in the boat and watched us for long.

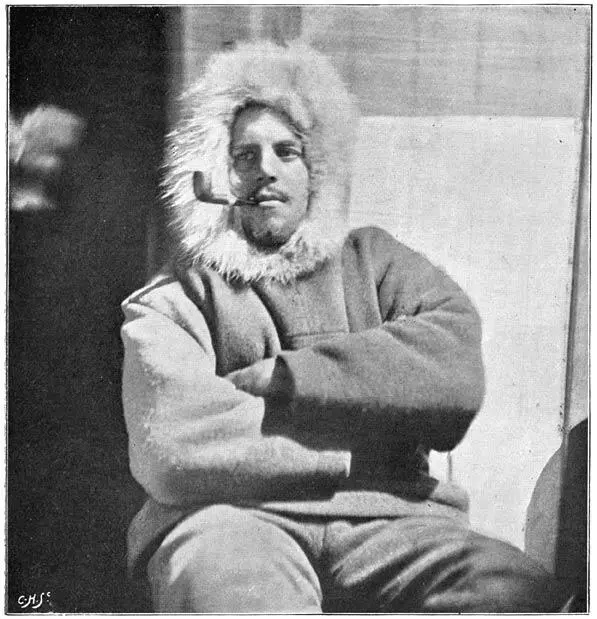

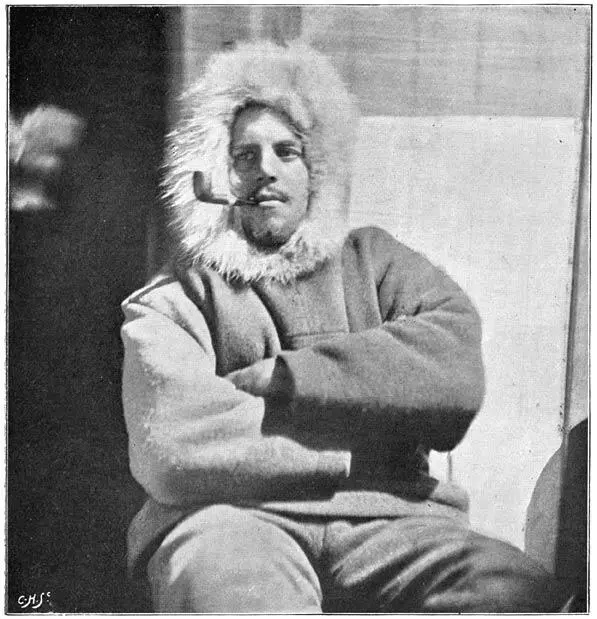

Sigurd Scott-Hansen

( From a photograph taken in December, 1893 )

We bore along the coast in good weather, past Christiansand. The next evening, June 27th, we were off the Naze. I sat up and chatted with Scott-Hansen till late in the night. He acted as captain on the trip from Christiania to Trondhjem, where Sverdrup was to join, after having accompanied his family to Steenkiær. As we sat there in the chart-house and let the hours slip by while we pushed on in the ever-increasing swell, all at once a sea burst open the door and poured in. We rushed out on deck. The ship rolled like a log, the seas broke in over the rails on both sides, and one by one up came all the crew. I feared most lest the slender davits which supported the long-boats should give way, and the boats themselves should go overboard, perhaps carrying away with them a lot of the rigging. Then twenty-five empty paraffin casks which were lashed on deck broke loose, washed backward and forward, and gradually filled with water; so that the outlook was not altogether agreeable. But it was worst of all when the piles of reserve timber, spars, and planks began the same dance, and threatened to break the props under the boats. It was an anxious hour. Sea-sick, I stood on the bridge, occupying myself in alternately making libations to Neptune and trembling for the safety of the boats and the men, who were trying to make snug what they could forward on deck. I often saw only a hotch-potch of sea, drifting planks, arms, legs, and empty barrels. Now a green sea poured over us and knocked a man off his legs so that the water deluged him; now I saw the lads jumping over hurtling spars and barrels, so as not to get their feet crushed between them. There was not a dry thread on them. Juell, who lay asleep in the “Grand Hotel,” as we called one of the long-boats, awoke to hear the sea roaring under him like a cataract. I met him at the cabin door as he came running down. It was no longer safe there, he thought; best to save one’s rags—he had a bundle under his arm. Then he set off forward to secure his sea-chest, which was floating about on the fore-deck, and dragged it hurriedly aft, while one heavy sea after another swept over him. Once the Fram buried her bows and shipped a sea over the forecastle. There was one fellow clinging to the anchor-davits over the frothing water. It was poor Juell again. We were hard put to it to secure our goods and chattels. We had to throw all our good paraffin casks overboard, and one prime timber balk after another went the same way, while I stood and watched them sadly as they floated off. The rest of the deck cargo was shifted aft on to the half-deck. I am afraid the shares in the expedition stood rather low at this moment. Then all at once, when things were about at their worst with us, we sighted a bark looming out of the fog ahead. There it lay with royals and all sails set, as snugly and peacefully as if nothing were the matter, rocking gently on the sea. It made one feel almost savage to look at it. Visions of the Flying Dutchman and other devilry flashed through my mind.

Читать дальше