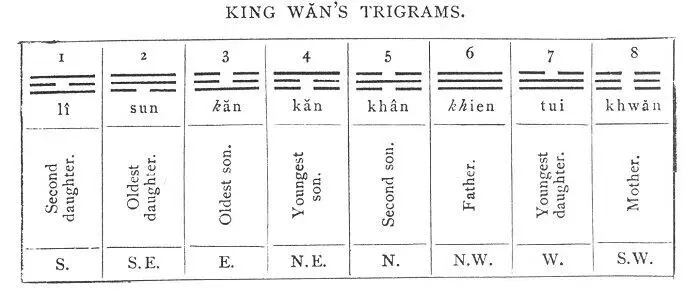

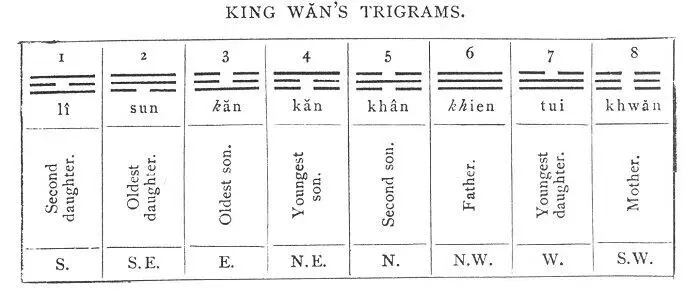

King Wăn altered the arrangement of the trigrams so that not one of them should stand at the same point of the compass as in the ancient plan. He made them also representative of certain relations among themselves, as if they composed a family of parents and children. It will be sufficient at present to give a table of his scheme.

KING WĂN'S TRIGRAMS

There is thus before us the apparatus with which the writer of the Appendix accomplishes his task. Let me select one of the shortest instances of his work. The fourteenth hexagram is  , called Tâ Yû, and meaning 'Possessing in great abundance.' King Wăn saw in it the symbol of a government prosperous and realising all its proper objects; but all that he wrote on it was 'Tâ Yû (indicates) great progress and success.' Unfolding that view of its significance, the Appendix says:--

, called Tâ Yû, and meaning 'Possessing in great abundance.' King Wăn saw in it the symbol of a government prosperous and realising all its proper objects; but all that he wrote on it was 'Tâ Yû (indicates) great progress and success.' Unfolding that view of its significance, the Appendix says:--

'In Tâ Yû the weak (line) has the place of honour, is grandly central, and (the strong lines) above and below respond to it. Hence comes its name of "Possession of what is great." The attributes (of its constituent trigrams, kh ien and lî) are strength and vigour, elegance and brightness. (The ruling line in it) responds to (the ruling line in the symbol of) heaven, and its actings are (consequently all) at the proper times. Thus it is that it is said to indicate great progress and success.'

In a similar way the paragraphs on all the other 63 hexagrams are gone through; and, for the most part, with success. The conviction grows upon the student that the writer has on the whole apprehended the mind of king Wăn.

I stated, on p. 32, that the name kwei-shăn occurs in this Appendix. It has not yet, however, received the semi-physical, semi-metaphysical signification which the comparatively modern scholars of the Sung dynasty give to it. There are two passages where it is found;--the second paragraph on Kh ien, the fifteenth hexagram, and the third on Făng, the fifty-fifth. By consulting them the reader will be able to form an opinion for himself. The term kwei denotes specially the human spirit disembodied, and shăn is used for spirits whose seat is in heaven. I do not see my way to translate them, when used binomially together, otherwise than by spiritual beings or spiritual agents.

K û Hsî once had the following question suggested by the second of these passages put to him:--'Kwei-shăn is a name for the traces of making and transformation; but when it is said that (the interaction of) heaven and earth is now vigorous and abundant, and now dull and void, growing and diminishing according to the seasons, that constitutes the traces of making and transformation; why should the writer further speak of the Kwei-shăn?' He replied, 'When he uses the style of "heaven and earth," he is speaking of the result generally; but in ascribing it to the Kwei-shăn, he is representing the traces of their effective interaction, as if there were men (that is, some personal agency) bringing it about 3.' This solution merely explains the language away. When we come to the fifth Appendix, we shall understand better the views of the period when these treatises were produced.

The single character shăn is used in explaining the thwan on Kwân, the twentieth hexagram, where we read:--

'In Kwân we see the spirit-like way of heaven, through which the four seasons proceed without error. The sages, in accordance with (this) spirit-like way, laid down their instructions, and all under heaven yield submission to them.'

The author of the Appendix delights to dwell on the changing phenomena taking place between heaven and earth, and which he attributes to their interaction; and he was penetrated evidently with a sense of the harmony between the natural and spiritual worlds. It is this sense, indeed, which vivifies both the thwan and the explanation of them.

5. We proceed to the second Appendix, which professes to do for the duke of K âu's symbolical exposition of the several lines what the Thwan K wan does for the entire figures. The work here, however, is accomplished with less trouble and more briefly. The whole bears the name of Hsiang K wan, 'Treatise on the Symbols' or 'Treatise on the Symbolism (of the Yî).' If there were reason to think that it came in any way from Confucius, I should fancy that I saw him sitting with a select class of his disciples around him. They read the duke's Text column after column, and the master drops now a word or two, and now a sentence or two, that illuminate the meaning. The disciples take notes on their tablets, or store his remarks in their memories, and by and by they write them out with the whole of the, Text or only so much of it as is necessary. Whoever was the original lecturer, the Appendix, I think, must have grown up in this way.

It would not be necessary to speak of it at greater length, if it were not that the six paragraphs on the symbols of the duke of K âu are always preceded by one which is called 'the Great Symbolism,' and treats of the trigrams composing the hexagram, how they go together to form the six-lined figure, and how their blended meaning appears in the institutions and proceedings of the great men and kings of former days, and of the superior men of all time. The paragraph is for the most part, but by no means always, in harmony with the explanation of the hexagram by king Wăn, and a place in the Thwan K wan would be more appropriate to it. I suppose that, because it always begins with the mention of the two symbolical trigrams, it is made, for the sake of the symmetry, to form a part of the treatise on the Symbolism of the Yî.

I will give a few examples of the paragraphs of the Great Symbolism. The first hexagram  is formed by a repetition of the trigram Kh ien

is formed by a repetition of the trigram Kh ien  representing heaven, and it is said on it:--'Heaven in its motion (gives) the idea of strength. The superior man, in accordance with this, nerves himself to ceaseless activity.'

representing heaven, and it is said on it:--'Heaven in its motion (gives) the idea of strength. The superior man, in accordance with this, nerves himself to ceaseless activity.'

The second hexagram  is formed by a repetition of the trigram Khwăn

is formed by a repetition of the trigram Khwăn  representing the earth, and it is said on it:--'The capacious receptivity of the earth is what is denoted by Khwăn. The superior man, in accordance with this, with his large virtue, supports men and things.'

representing the earth, and it is said on it:--'The capacious receptivity of the earth is what is denoted by Khwăn. The superior man, in accordance with this, with his large virtue, supports men and things.'

The forty-fourth hexagram, called Kâu  , is formed by the trigrams Sun

, is formed by the trigrams Sun  , representing wind, and Kh ien

, representing wind, and Kh ien  representing heaven or the sky, and it is said on it:--'(The symbol of) wind, beneath that of the sky, forms Kâu. In accordance with this, the sovereign distributes his charges, and promulgates his announcements throughout the four quarters (of the kingdom).'

representing heaven or the sky, and it is said on it:--'(The symbol of) wind, beneath that of the sky, forms Kâu. In accordance with this, the sovereign distributes his charges, and promulgates his announcements throughout the four quarters (of the kingdom).'

Читать дальше

, called Tâ Yû, and meaning 'Possessing in great abundance.' King Wăn saw in it the symbol of a government prosperous and realising all its proper objects; but all that he wrote on it was 'Tâ Yû (indicates) great progress and success.' Unfolding that view of its significance, the Appendix says:--

, called Tâ Yû, and meaning 'Possessing in great abundance.' King Wăn saw in it the symbol of a government prosperous and realising all its proper objects; but all that he wrote on it was 'Tâ Yû (indicates) great progress and success.' Unfolding that view of its significance, the Appendix says:-- is formed by a repetition of the trigram Kh ien

is formed by a repetition of the trigram Kh ien  representing heaven, and it is said on it:--'Heaven in its motion (gives) the idea of strength. The superior man, in accordance with this, nerves himself to ceaseless activity.'

representing heaven, and it is said on it:--'Heaven in its motion (gives) the idea of strength. The superior man, in accordance with this, nerves himself to ceaseless activity.' is formed by a repetition of the trigram Khwăn

is formed by a repetition of the trigram Khwăn  representing the earth, and it is said on it:--'The capacious receptivity of the earth is what is denoted by Khwăn. The superior man, in accordance with this, with his large virtue, supports men and things.'

representing the earth, and it is said on it:--'The capacious receptivity of the earth is what is denoted by Khwăn. The superior man, in accordance with this, with his large virtue, supports men and things.' , is formed by the trigrams Sun

, is formed by the trigrams Sun  , representing wind, and Kh ien

, representing wind, and Kh ien