'In the Yî there are four things characteristic of the way of the sages. We should set the highest value on its explanations, to guide us in speaking; on its changes, for the initiation of our movements; on its emblematic figures, for definite action, as in the construction of implements; and on its prognostications, for our practice of divination.'

This is followed by seven paragraphs expanding its statements, and we come to the last one of the chapter which says,--'The Master said, "Such is the import of the statement that there are four things in the Yî, characteristic of the way of the sages."' I cannot understand how it could be more fully conveyed to us that the compiler or compilers of this Appendix were distinct from the Master whose words they quoted, as it suited them, to confirm or illustrate their views.

In the fourth Appendix, again, we find a similar occurrence of the formula of quotation. It is much shorter than the third, and the phrase, 'The Master said,' does not come before us so frequently; but in the thirty-six paragraphs that compose the first section we meet with it six times.

Moreover, the first three paragraphs of this Appendix are older than its compilation, which could not have taken place till after the death of Confucius, seeing it professes to quote his words. They are taken in fact from a narrative of the Ȝo K wan, as having been spoken by a marchioness-dowager of Lû fourteen years before Confucius was born. To account for this is a difficult task for the orthodox critics among the Chinese literati. K û Hsî attempts to perform it in this way:--that anciently there was the explanation given in these paragraphs of the four adjectives employed by king Wăn to give the significance of the first hexagram; that it was employed by Mû K iang of Lû; and that Confucius also availed himself of it, while the chronicler used, as be does below, the phraseology of 'The Master said,' to distinguish the real words of the sage from such ancient sayings. But who was 'the chronicler?' No one can tell. The legitimate conclusion from KO's criticism is, that so much of the Appendix as is preceded by 'The Master said' is from Confucius,--so much and no more. I am thus obliged to come to the conclusion that Confucius had nothing to do with the composition of these two Appendixes, and that they were not put together till after his death. I have no pleasure in differing from the all but unanimous opinion of Chinese critics and commentators. What is called 'the destructive criticism' has no attractions for me; but when an opinion depends on the argument adduced to support it, and that argument turns out to be of no weight, you can no longer set your seal to this, that the opinion is true. This is the position in which an examination of the internal evidence as to the authorship of the third and fourth Appendixes has placed me. Confucius could not be their author. This conclusion weakens the confidence which we have been accustomed to place in the view that 'the ten wings' were to be ascribed to him unhesitatingly. The view has broken down in the case of three of them;--possibly there is no sound reason for holding the Confucian origin of the other seven.

I cannot henceforth maintain that origin save with bated breath. This, however, can be said for the first two Appendixes in my arrangement, that there is no evidence against their being Confucian like the fatal formula, 'The Master said.' So it is with a good part of my fifth Appendix; but the concluding paragraphs of it, as well as the seventh Appendix, and the sixth also in a less degree, seem too trivial to be the production of the great man. As a translator of every sentence both in the Text and the Appendixes, I confess my sympathy with P. Regis, when he condenses the fifth Appendix into small space, holding that the 8th and following paragraphs are not worthy to be translated. 'They contain,' he says, 'nothing but the mere enumeration of things, some of which may be called Yang, and others Yin, without any other cause for so thinking being given. Such a method of procedure would be unbecoming any philosopher, and it cannot be denied to be unworthy of Confucius, the chief of philosophers 1.'

I could not characterise Confucius as 'the chief of philosophers,' though he was a great moral philosopher, and has been since he went out and in among his disciples, the best teacher of the Chinese nation. But from the first time my attention was directed to the Yî, I regretted that he had stooped to write the parts of the Appendixes now under remark. It is a relief not to be obliged to receive them as his. Even the better treatises have no other claim to that character besides the voice of tradition, first heard nearly 400 years after his death.

4. I return to the Appendixes, and will endeavour to give a brief, but sufficient, account of their contents.

The first bears in Chinese the name of Thwan K wan, 'Treatise on the Thwan,' thwan being the name given to the paragraphs in which Wăn expresses his sense of the significance of the hexagrams. He does not tell us why he attaches to each hexagram such and such a meaning, nor why he predicates good fortune or bad fortune in connexion with it, for he speaks oracularly, after the manner of a diviner. It is the object of the writer of this Appendix to show the processes of king Wăn's thoughts in these operations, how he looked at the component trigrams with their symbolic intimations, their attributes and qualities, and their linear composition, till he could not think otherwise of the figures than he did. All these considerations are sometimes taken into account, and sometimes even one of them is deemed sufficient. In this way some technical characters appear which are not found in the Text. The lines, for instance, and even whole trigrams are distinguished as kang and z âu, hard or strong' and 'weak or soft.' The phrase Kwei-shăn, 'spirits,' or 'spiritual beings,' occurs, but has not its physical signification of 'the contracting and expanding energies or operations of nature.' The names Yin and Yang, mentioned above on pp. 15, 16, do not present themselves.

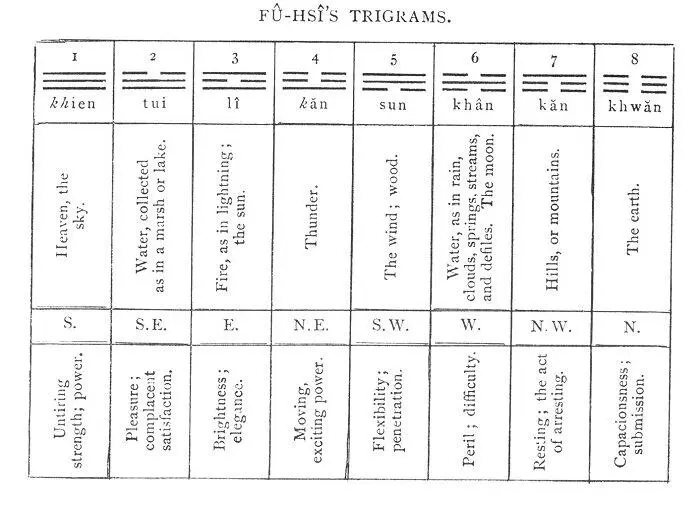

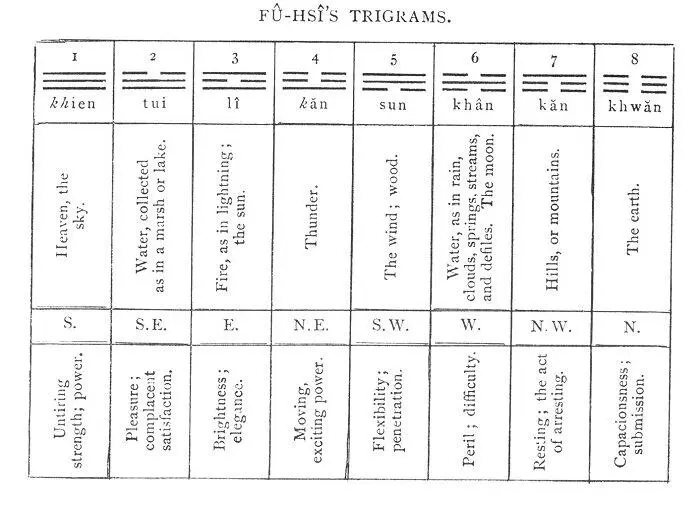

I delineated, on p. 11, the eight trigrams of Fû-hsî, and gave their names., with the natural objects they are said to represent, but did. not mention the attributes, the virtutes, ascribed to them. Let me submit here a table of them, with those qualities, and the points of the compass to which they are referred. I must do this because king Wăn made a change in the geographical arrangement of them, to which reference is made perhaps in his text and certainly in this treatise. He also is said to have formed an entirely different theory as to the things represented by the trigrams, which it will be well to give now, though it belongs properly to the fifth Appendix.

FÛ-HSÎ'S TRIGRAMS

The natural objects and phenomena thus represented are found up and down in the Appendixes. It is impossible to believe that the several objects were assigned to the several figures on any principles of science, for there is no indication of science in the matter: it is difficult even to suppose that they were assigned on any comprehensive scheme of thought. Why are tui and khân used to represent water in different conditions, while khân, moreover, represents the moon? How is sun set apart to represent things so different as wind and wood? At a very early time the Chinese spoke of 'the five elements,' meaning water, fire, wood, metal, and earth; but the trigrams were not made to indicate them, and it is the general opinion that there is no reference to them in the Yî 2.

Again, the attributes assigned to the trigrams are learned mainly from this Appendix and the fifth. We do not readily get familiar with them, nor easily accept them all. It is impossible for us to tell whether they were a part of the jargon of divination before king Wăn, or had grown up between his time and that of the author of the Appendixes.

Читать дальше