an integrated process which involves working to identify and exploit win-win solutions which respect nature and are acceptable to both project proponents and environmental stakeholders. It is a philosophy which needs to be applied early in a project when flexibility is still possible (PIANC 2011b).

Nature-based solutions, popularized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), include infrastructure eco-design in their definition (Cohen-Shacham et al . 2016): “Nature-based solutions are actions built on ecosystems to address global challenges such as climate change or natural risk management”, for example, the biogenic seawall for coastline protection ( Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Diagram of the definition of nature-based solutions, proposed by the IUCN, where conventional infrastructure is cited as an application (Cohen-Shacham et al. 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/pioch/marine.zip

Internationally, our definition of eco-design is related to the terms “green engineering”, “eco-engineering”, “nature-based solution” and “eco-design” (Pioch et al . 2018). It now seems interesting to us to better draw the spirit of this approach from the sources of inspiration of eco-design dedicated to marine environments, through the Japanese experience.

1.3. Japanese inspiration

It is in Japan, an archipelago country turned by necessity towards the sea, where the observation of nature is an art as much as a deep aspiration, that the ideas on the development of the seabed have been developed.

It was around the 17th century, during the reign of Emperor Jôo, that fish houses, reefs and artificial fishing habitats were built near the coast. It is within this culture of Sato-umi , literally “the sea where people live”, and this vision of a fertile and rich sea for those who know how to change it that the Japanese idea of eco-design was developed (Yanagi 2012).

The very root of the word œkodesign ( oikos , from the Greek word for home or house) is completely in line with that of Sato-umi , based around the notions conveyed by ecumene 14and ecology. We can also find in this vision the inspiration developed by Rosenzweig and Michael (2003) for the ecology of reconciliation, where biodiversity and human development are closely intertwined in our “common home”.

1.3.1. Influence of the Japanese vision for sea-friendly development projects

François Doumenge 15, in his book Le Japon et l’exploitation de la mer (1961), was impressed by “the incredible creativity of this people towards maritime productive development”. He emphasized the empirical and traditional approach of Asian societies, where the observation of nature, expressed in the Shinto spiritual tradition (or Kani-michi , the “voice of the gods”), gave a familiar closeness between humans and a deified nurturing nature, but in proximity, not in superiority (Doumenge 1961, 1966). In fact, the spirituality developed around nature and Shinto is more a way of life than a religion in the Western sense, according to Doumenge. This vision has also influenced Augustin Berque (1996). He admits in his reflections to having been inspired by the Japanese author Watsuji Tetsurō to clarify his vision of the ecumene where the human is intimately dependent on the natural environment. The sea ( umi ) is both a vital and respected environment because it is a place of intense spiritual activity where the kani (familiar deities) live and where the souls of the dead spend time. The Japanese view of the sea, and the underwater world, is also one that is comparable to our view of our earthly, poetic and scenic landscapes ( Figure 1.4).

Moreover, the two basic principles of Japanese coastal maritime law (Amako 2015) are based on:

– the “Yoro Code” (養老律令 enacted in 757): “coastal areas are of common (public) use and are managed by the users themselves”;

– the “Ritsuryo Rules” (律令要約 enacted in 1741): “coastal areas are managed by delegation to local fishing communities”.

The management of natural marine environments closest to the activities carried out there, in this case fishing, is a marker structuring Japanese thinking.

Figure 1.4. Kushimoto Marine Park, protected for the value of underwater landscapes (photo: S. Pioch)

1.3.2. The Japanese Sato-umi

This particular view, and the predominance of the sea, is explained by the geography of Japan, made up of five large islands and 6,847 islands and islets. The exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Japan, with 4,050,000 km 2, is also the sixth largest in the world.

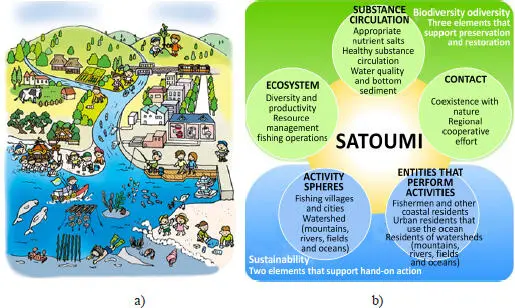

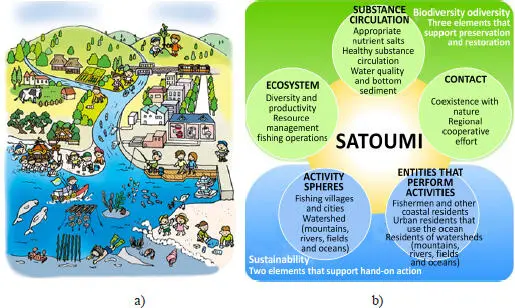

With only 14% of the country’s land area available as arable land, the submerged volume of the sea has long been an essential element in providing the country’s food resources, along with rice cultivation. The ICZM vision is therefore naturally developed in Japan under the term Sato-umi ( Figure 1.5).

The term was proposed by Yanagi; it comes from its terrestrial counterpart Satoyama , where sato refers to a place where people live and yama to a forest; the combination of the two terms then leads to a third definition: “the forest near the place where people live”. Sato-yama came from a reaction that we might call neo-modernist, questioning the idea that nature would reach its fullest potential without the work of humans (Dublin et al . 2014). This is what is developed by Lassus (2002) in his book Harmonie et règles urbaines , where the work of humans respects biodiversity, creating different interactive biotopes.

Figure 1.5. The concept of Sato-umi, where humans interact with the aquatic environment for mutual benefit: (a) Japanese Ministry of the Environment (2015); (b) Yanagi (2007)

This idea of Sato-umi , close to the European vision of ICZM 16, reinvests the contributions of ecological engineering to integrate nature into the design of infrastructures.

1.3.3. Artificial marine habitats: Japanese origin of inspiration for eco-design

Japan is undoubtedly considered as the world leader in the successful management of the seabed, as much in terms of application (stability of coastal fisheries) as perspective (Bailly 1989; Baine 2001). Extensive coastal mariculture (or marine-ranching) began with the great interest of this maritime nation in the creation of “fish houses”, habitats adapted to the needs and functions necessary to increase underwater life. Thus, the first Japanese reefs, or artificial habitats (AHs), were described between 1652 and 1655 (during the reign of Emperor Jôo). They consisted of wrecks filled with stones to extend the exploitable fishing areas near the village. The technical description is very precise, and the choice of materials (stones and timber from ships) is linked to questions of habitat (volume, ecological functions, target species, stage of development) and durability. However, it was not until the 20th century that this structural diversity really developed in Japan, and then from the 1950s onwards for the rest of the world.

Читать дальше