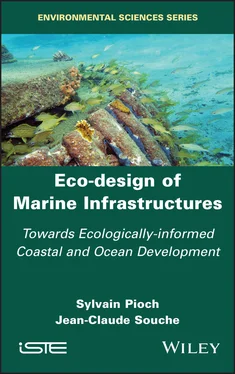

Sylvain Pioch

Jean-Claude Souche

July 2021

1 1The work of McHarg in the area of landscape architecture, gathered in his famous Design with Nature, served as a basis for our extrapolation to the submerged, underwater marine domain.

This book is dedicated to our families: Élise, Guilhem, Céleste, Raphaëlle and Julianne, and Sophie, Juliette, Rémi, Éloïse and Alexis, who are the driving force of our lives. We would also like to thank all those who, through their lives, actions and convictions, seek to build a fairer and more beautiful world where humankind will be able to consider all the other forms of life on the planet of which it is only the host.

This book is the compilation of 30 years of professional practice acquired as an environmental engineer in planning and impact studies (S. Pioch) and as a civil engineer (J.-C. Souche), then as lecturers and researchers in University Montpellier 3 and Mine Telecom Institute of Alès or simply as divers.

Beyond our common passion for the sea, it seemed unavoidable to merge our experiences as the need to design and build marine structures differently is urgent. It is also with modesty that we propose this work to readers, without claiming it to be exhaustive or the absolute truth. We simply provide a testimony and methodological tracks that we have tested in the field, with actors involved in development.

We would like to thank Régis Dumay, Marie Salgues, Jean Bougis, Philippe Saussol and Jean-Marie Miossec for their active help in the elaboration of this book, as well as the company Beuchat for the diving equipment. A special thought for Françoise Gaill for her constant support. We would also like to thank all the contributors who shared their testimonies with us in order to make this book a moment of sharing of experiences in France and abroad, which we hope the readers will appreciate:

– Alexandra Agostini, Anne Rioux, Aurore Léocadie, Osanne Paireau, Katherine A. Dafforn (Australia), Louise Firth (UK) and Shimrit Perkol-Finkel (Israel);

– André Grosset, Bernard Sigros, Cyril Giraudel, Cyrille Taioni, Etienne Cunge, Fabrice Javel, Frédéric Martarèche, Jean-Louis Gaziello, Jean-Michel Cathala, Michel Fons, Patrick Guiraud, Pierre Roy, Romaric Vicente, Marcel Stive (Netherlands), Jean-Luc Nguyen (Monaco) and Richard Spieler (USA).

May this modest work inspire us to think differently and to eco-design marine works, for the mutual benefit of the sea and humankind.

1

Principles and Genesis of Maritime Eco-design

The global ecological crisis is concomitant with the Anthropocene, this new geological era in which humans have become the central actors of pressures on the planet (Crutzen 2006). Indeed, the recent IPBES report (IPBES 2019) makes a damning assessment of the state of biodiversity since the beginning of the industrial era two centuries ago: 75% of the land has been altered by humans (one-third of the land consuming three-quarters of the available water resources is agricultural), 66% of the oceans are threatened by humans and more than 85% of wetlands have been destroyed. It is therefore our actions on this unique planet that are holding back our own future. The logic of this observation would lead us to stop, or at least to slow down, the well-known causes of this disaster (in decreasing order): (1) artificialization and land use; (2) resource exploitation (fishing, forestry, etc.); (3) climate change; (4) pollution (plastics, chemical residues, etc.); and (5) invasive species (IPBES 2019). Thus, artificialization and land use would be our main problem. In addition to agriculture, it is the issue of urbanization and its consequences (cities, ports, mines, industries and roads) that is the most important because it leads to an artificialization of environments that is difficult to reverse. If we look at the forecasts, we can see not only a continuity but also an acceleration of global urbanization, both on the continents and at sea. No less than 60,000 billion US dollars will be invested in infrastructure between 2019 and 2040 (in the 56 countries representing 88% of the world’s GDP (Global Infrastructure Hub and Oxford Economics 2017)), more than 1.2 million km 2will be urbanized by 2030, in just 10 years, that is, an increase of 185% compared to 1970–2000 (Seto et al . 2012), and 3–4.7 million km 2of roads will be created by 2050, an increase of 25% compared to the current annual rate (Meijer et al . 2018).

This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in coastal areas, as 8 of the 10 global megacities are located on shores, such as Lagos, Tokyo, Jakarta and New York. The global maritime infrastructure footprint was approximately 32,000 km 2in 2018 (Bugnot et al . 2021). It is expected to reach 39,400 km 2by 2028, a territory equivalent to the state of Bhutan! However, the area of seascapes impacted by these structures was also estimated to be between 1 and 3.4 million km 2in 2018, with an increase of 50–70% expected by 2028, which is comparable to the global extent of urbanized areas (estimated at 0.02–1.7% of the land mass (Bugnot et al . 2021)). On the French coast, the rate of occupation doubled between 1965 and 1980 1. Between 2000 and 2006, no less than 6,809 ha were destroyed for the construction of harbors, dikes, embankments and other structures 2. For example, in Hérault, a department in the Occitanie region, close to the Mediterranean Sea (southern France), the level of urbanization in 2015 on a narrow coastal strip of 15 km was close to 70%, with no less than three-quarters of the population concentrated there (DREAL Occitanie). In the international literature, we speak of a global “coastal squeeze”. This phrase, introduced by Doody (2004), is based on the threat to coastal development caused by the dual effect of rising sea levels and the explosion of human activities. There is an incoherence between human and the needs of our planet, especially in the urgent matter of the artificialization of natural environments, notably coastal ones. Urbanization remains the result of a development that is still too predatory of space.

Faced with the enormous challenge of a renaturation of culture (Pelt 1977), for a livable future of humankind, it becomes crucial to improve the consideration of biodiversity in territorial planning projects. We will focus here on the potential for nature-friendly planning, trying to integrate its functional needs as a fully-fledged objective in the design of infrastructures.

1.1. Principles of maritime eco-design

The actions taken to allow for the “natural” environment (we will use this term here in relation to the word “ecosystem”) for the operation of maritime works are varied. In the case of ports, these include the control and reduction of discharges, energy, sediment, waste and water management, environmental management plans (compliant since 2013), natural infrastructure master plans – including a natural heritage master plan – and Natura 2000 operators within the port perimeter (e.g. the Grand Port Maritime of Dunkirk).

At the same time, several tools designed to provide (voluntary) environmental certification are also available to project owners: AFAQ Clean Ports, ISO 14001, Blue Flag and the latest “Clean Port” certification active in biodiversity 3, in March 2018. These certifications are often accompanied by communication programs, such as the “Green Port” 4, “Year of Biodiversity” and “Port Biodiversity Index”, or information panels and stands proposed by the ports’ sustainable development departments, suppliers of “eco-” equipment or operators ( Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Public presentation panel on port biodiversity in the port of Kernével, one of the first two ports in Brittany to be certified “Clean Ports Active in Biodiversity”5 in 2018 (photo: ©APPB)

Читать дальше