In the past 20 years, the technomorphic model has been greatly modified in all areas of dentistry because research and practice have increasingly focused on the biologic principles of dental activity. Nevertheless, many dentists continue to equate better care with better technique.

The authors of this book confront these attitudes from the outset. Better basic treatment of CMD cases cannot be achieved simply by better technique but by a new way of thinking that places patients, their suffering, and what they tell their dentists center stage. Readers will only succeed in adopting a new and different way of thinking if they can free themselves from conventional, outmoded patterns of activity. This book invites them to do so. It offers those with a professional interest a clear guide to help them address the issue of CMD in theory and practice and provide their CMD patients with the best possible treatment. Great emphasis is placed on the importance of history taking. Recognizing this and drawing the necessary conclusions about diagnosis and treatment are key to the new way of thinking, which makes appropriate clinical decisions possible in CMD cases.

The book is divided into two parts. The first part presents a practical guide to the basic treatment of CMD patients, while the second builds on that basic knowledge by exploring scientific and theoretical principles in more depth. The two parts complement each other to form a “rounded” and complete picture of the present state of the art. This is why readers are strongly encouraged to study both parts. The second part examines scientific perspectives that not only reveal other courses of action but help interested practitioners to critically evaluate their own experiences.

It is possible to improve the treatment of patients with CMD. This book documents the clinical paths that will lead to a targeted and evidence-based therapeutic approach. It is up to all of us—as members of the dental profession—to seize this initiative and pursue the paths that are laid out for us.

Prof Dr Winfried Walther

Director

Dental Academy for Continuing Professional Development

Karlsruhe, Germany

Preface

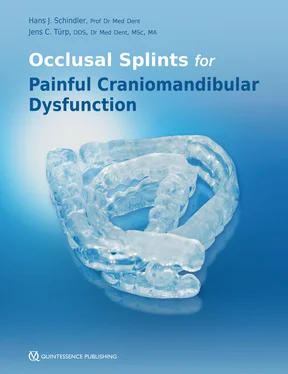

The publication of this book might prompt some people to think, “Surely not another book about craniomandibular dysfunction (CMD)!” Although this might, at first sight, be a justifiable reaction, the authors are not aware of an entire book dealing with the subject of occlusal splints that has been published in the past decade.

Yet the times are constantly changing and, in the process, scientific advances are being made that inevitably lead to new discoveries. In the area of functional therapy, this is particularly true of the use of occlusal splints to treat painful CMD. There is often a considerable delay, however, before new knowledge makes its way into dental practices. Regrettably, knowledge transfer tends to take a long time (too long), and several aspects promote and negatively reinforce this situation. Three examples of these delaying factors are worth noting:

1 The preference for personal experience (that is not monitored) rather than evidence-based knowledge derived from scientific studies

2 The fact that, despite the unlimited access at least to abstracts from prominent specialty publications, too little use is made of the opportunities for expanding knowledge through open-access electronic libraries (eg, due to a lack of knowledge about how to research relevant journal articles and how these can be acquired, as well as the fact that major publications are only accessible for a fee)

3 The often poorly defined term “patient satisfaction” being used as a practice-specific measure of “success”

In this context it should be clear that patient-centered clinical decisions can no longer be based solely on the practitioner’s individual clinical experience. Experience is undoubtedly important, but it is not enough for scientifically based practice that is supported by evidence. Instead, knowledge of the current state of the art in clinical research (in the form of published study results) is essential in addition to personal experience.

The values, wishes, and concerns of the patient should be regarded as the third, equally significant pillar. Only when these three aspects are incorporated equally into individual decision making on the course of action can this be called scientifically based (commonly known as “evidence-based”) dentistry. Therefore, evidence-based dentistry automatically includes the aspect of participatory decision making. It can thus claim to be both a beneficial and a self-determined form of medicine. On the other hand, evidence-based dentistry does not mean simply following the recommendations drawn from scientific guidelines or systematic reviews; this would be “cookbook medicine,” which in many instances would not do justice to the individual case.

So much for the principle, now for the “reality.” One of the authors of this book recently gave a rather lengthy lecture on the subject of painful CMD for a continuing education program. After about an hour, one audience member raised his voice to complain angrily that what he had heard was hardly any use to his practical work (it is worth noting that he had blissfully slept through a substantial part of the lecture). Partly this angry comment and partly the authors’ decades of extensive teaching work prompted a thorough rethink and led to the following conclusions—though not necessarily a new realization:

The classic structure of knowledge transfer, especially in print media, has some serious didactic shortcomings. It is widely accepted that the diagnostic routines and treatment models developed in clinical institutions and specialist centers are barely suited to the reality of dentists’ offices. Furthermore, treatment and co-therapy recommendations are frequently reduced to succinct pointers, such as “splint therapy,” “home exercises,” or “education,” without providing any real help as to where, when, and how these recommendations should be carried out. Attentive readers will notice that the present authors are not afraid to broach the subject of (even their own) shortcomings and try hard, whenever possible, to rectify them in this book.

Knowledge and the resulting (potential) clinical benefit to dental practice obviously cannot be transmitted directly, especially since only a few dentists—even in universities, as hard as that is to believe—take advantage of access to the specialist scientific literature during the course of their clinical decision making. Furthermore, the experience and expertise of “professionals,” who process the data to make it “easily digestible” even for non-scientists, are required for others to derive benefit from published research results. In the treatment of painful CMD, there is barely any equivalent to the instructions that are familiar from medicine in terms of directives, guidelines, or clinical recommendations (the compulsory nature of these standards of proper medical treatment decreasing in descending order). Another factor is that the patients included in research studies do not usually represent patients treated in dental practices, who account for around 80% of the general demand for CMD treatment. These distortions of the patient populations naturally lead to misunderstandings between clinicians based in a university setting and office-based practitioners (this aspect is dealt with in more depth in relation to “chronic CMD”). These misunderstandings stand in the way of successful treatment of patients with painful CMD, who for the most part are easily treatable. Dental routines such as minimum diagnostics, therapeutic interocclusal records, affordable fabrication of occlusal splints, physiotherapy, and behavior modification therapy tend to be described with only limited practical applicability. Furthermore, these aspects are all too often burdened with inappropriate instructions, which, in the worst case, lack any scientific foundation and, apart from that, frequently take up unnecessary amounts of time in the dental practice. A particularly serious aspect is that the term “rehabilitation” hardly ever crops up in practical day-to-day treatment. Let us not forget: pain reduction or elimination of pain is the original and primary goal of dental treatments.

Читать дальше