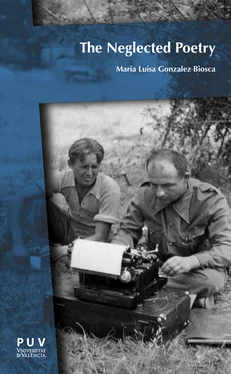

The next steps were the searches for more data, personal memoirs and photographs through anthologies, literary magazines published by brigadists, internet sources and websites, biographies, catalogues, libraries, battlefields and museum websites, as for example, the Imperial War Museum, among others.

I contacted the Asociación de Amigos de las Brigadas Internaciones in Madrid by telephone and Severiano Montero, the president of the association at that time, answered my questions about a topic which was new for me. I wondered where they had fought, and if they had been in the trenches for long periods of time. Severiano Montero, a scholar of history and professor, suggested that I participate in the guided marches to the battlefields where the brigadists had fought. He also told me to visit the Conde Duque Newspaper Library in Madrid, where microfilmed diaries of The Volunteer for Liberty , published from February 1937 until February 1938, are preserved on microfilm.

Reading those old periodicals published at that time in English in a country, where the majority of the population was illiterate, was an emotional moment of the research. Then, my field work continued when I rang the newspaper library of the Pavellón de la República which belongs to the University of Barcelona and, fortunately, the archivist confirmed there were some issues of the The Volunteer for Liberty . However, the archivist told me I needed a letter of presentation from the dean of the University of Valencia to have access to the newspapers. Other places, such as the Humanities Library at the Valencia University, the newspaper library in Valencia, the newspaper library of the Ateneo Mercantil and the Institute Française of Valencia, were very useful. One of the most interesting archives that I worked with through the Internet is the Abraham Lincoln Brigades Archive in New York, where there is a great deal of official and personal data about the American brigadists.

Other valuable sources of first-hand information were the diaries, biographies or novels written by brigadists, where they relate their memories, and the ones written by war correspondents that tell a great deal about their experiences and implications with the “causa.” Many war correspondents, such as Martha Gelhorn, Virginia Cowles, Sefton Delmer, Josephine Herbst, Ernest Hemmingway, Langston Hughes, Charly Buckley, Herbert Mathews and John Whitaker spoke clearly about the facts of the war where they lived close to the fighting. Their vision of the personal tragedies of the brigadists, the popular army and the Spanish civilians reflected the professionalism of the good journalists who wrote what they saw without being afraid of the threat of censorship and its consequences because they were observers, journalists and protagonists all at the same time.

Even though I found books in the archives they were not sufficient enough for the investigation. Therefore, it was necessary to look for and buy all the anthologies, and most of the personal memoirs, essays, criticisms, biographies and history books on the Internet and from abroad. Sometimes there were handicaps because some books did not arrive on time, others were out of print and I had to look for them in other places. I had to reorder books and cancel other orders. Finally, I was able to compile a great deal of information to be able to carry out the research.

Another helpful source of information has been Ray Hoff, the son of Harold Hoff, an American brigadist of the XV Brigade. Ray sent me a facsimile of all the issues of The Volunteer of Liberty . He also sent other documents about the brigades, poems, pictures, and letters and has always been willing to help in any way possible.

1.2. Development of the Research

Taking into account that this chapter also deals with the necessary field work for the qualitative research, the methodology depended to a large extent on the knowledge of the historical context to which the brigadists belonged, and the consequences that the Spanish war had on their lives. The normal day-to-day routine of millions of citizens was interrupted by the coup d’état led by a group of rebel generals against the legality of the Spanish Republic government. The experience of the war is reflected in their poetry; they were involved in events that would change their lives forever. The worldwide scenario was changing dramatically during the Spanish Civil War, so, the intellectuals from abroad, who supported the Spanish Republic, answered the tragic appeal of Spain with their poetry.

A comparison between the legacy of the poetry written by the three groups will helped to single out what issues and aesthetic currents influenced these poets. Visiting natural scenarios, such as Belchite, Benicàssim, Brunete or Jarama, where the brigadists fought and that inspired most of the poetry they wrote, a part of the global process of the qualitative research of how things took place and how they progressed. Therefore, I visited some of the battlefields and places where events occurred. I also had the opportunity to listen to the experiences of some brigadists through the testimony of their children, Raymond Hoff and James Neugass, the sons of Harold Hoff and James Neugass, both of them members of the XV Brigade.

One of the most touching moments of the research was during the homage in November 2012 to the International Brigades at the Complutense University in Madrid, one of the first places where the brigadists defended the city from the attacks of the rebels. There I introduced myself to one of the last British brigadists who was still alive, David Lomon. I thanked him for what he had done for my country, Spain. Then he held my hand, put it against his chest and said, “You do not have to thank me. I did it because it came from my heart.” After the homage, I interviewed him, and I also asked about Clive Branson, another brigadist who had been captured with him by the Italian fascist infantry during the retreats in March, 1938, after the fall of Belchite. Both of them had been sent to the concentration camp of San Pedro de Cardeña in Burgos, where Branson had written poems and made sketches of the brigadist prisoners. Then David remembered that Branson had made a charcoal portrait of him. This picture is presently at the Max Memorial Library in London. David Lomon died a few weeks later.

1.3. Selection of the Poets from the XV International Brigade

Traditionally, poetry has been used as propaganda of war with the intention to gain support of the people, and that was what the Spanish Republic needed in order to collect funds for the refugees, food, medicines and other supplies for the Spanish people. Thanks to the initiative by Nancy Cunard to publish the survey “Are you for or against the war?” in 1937, many poems from Canada, England, Ireland, and also from the United States were published in favour of the Spanish Republic. This made the Spanish “causa” very popular around the world. It also helped the citizens to be aware of what really was happening with the agreement of non-intervention. The questionnaire explained that the agreement was a farce, because two of the nations that had already signed it, Germany and Italy, had invaded Spain and supported the rebel General Francisco Franco.

The corpus of poets chosen is based on the experience the brigadists went through while serving on the Loyalist side. Poems written by the nurses and journalists, as for example, Langston Hughes, who had spent three months with the XV Brigade, were also included.

The continuous references to the land were crucial: the trenches, the anguish, the fear of death, the blitzed cities, the hospital, the ambulance, etc. This poetry, mainly based on personal experience of the war, did not idealize it, although the poets defended the fight for their ideals.

Читать дальше