NIGHT-FLOWERING CACTUS

I know my time, which is obscure, silent and brief

For I am present without warning one night only.

When sun rises on the brass valleys I become serpent.

Though I show my true self only in the dark and to no man

(For I appear by day as serpent)

I belong neither to night nor day.

Sun and city never see my deep white bell

Or know my timeless moment of void:

There is no reply to my munificence.

When I come I lift my sudden Eucharist

Out of the earth’s unfathomable joy

Clean and total I obey the world’s body

I am intricate and whole, not art but wrought passion

Excellent deep pleasure of essential waters

Holiness of form and mineral mirth:

I am the extreme purity of virginal thirst.

I neither show my truth nor conceal it

My innocence is descried dimly

Only by divine gift

As a white cavern without explanation.

He who sees my purity

Dares not speak of it.

When I open once for all my impeccable bell

No one questions my silence:

The all-knowing bird of night flies out of my mouth.

Have you seen it? Then though my mirth has quickly ended

You live forever in its echo:

You will never be the same again. 26

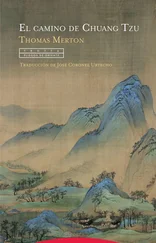

In a prophetic vein he wrote the lines with which I will conclude, a profound meditation which finds its correspondence in the Biblical myth of the fall of man from Eden but also in the guise of oriental sutras and in the Buddhist notion of kensho . They are the tacit expression of the unspeakable, of a wind alien to definitions, of the ineffable love which is always hovering underneath all of Merton’s words. All this is quite revealing and it confirms comments I once heard from Father Mathew Kelty at Gethsemani: “He belonged to no one. He could not be categorized, labelled, pigeon-holed […] the fire in him burned not only himself, but many around him as well.” May the poem speak for itself:

THE FALL

There is no where in you a paradise that is no place and there

You do not enter except without a story.

To enter there is to become unnameable.

Whoever is there is homeless for he has no door and no identity with

which to go out and to come in.

Whoever is nowhere is nobody, and therefore cannot exist except as

unborn:

No disguise will avail him anything

Such a one is neither lost nor found.

But he who has an address is lost.

They fall, they fall into apartments and are securely established!

They find themselves in streets. They are licensed

To proceed from place to place

They now know their own names

They can name several friends and know

Their own telephones must some time ring.

If all telephones ring at once, if all names are shouted at once and all

cars crash at one crossing:

If all cities explode and fly away in dust

Yet identities refuse to be lost. There is a name and number for

everyone.

There is a definite place for bodies, there are pigeon holes for ashes:

Such security can business buy!

Who would dare to go nameless in so secure a universe?

Yet, to tell the truth, only the nameless are at home in it.

They bear with them in the center of nowhere the unborn flower of

nothing:

This is the paradise tree. It must remain unseen until words end and

arguments are silent. 27

Meaningful intuitions have appeared and disappeared with generous audacity throughout this selection, intuitions to which Merton faithfully returns a thousand and one times as part of his task of criticism and ruthless discovery. We cannot ignore these examples. As manifestations of the Living Word, they constantly exhort us not to take the appearance of reality as if it were Truth, not to be scared of ceasing to exist, not fearfully lacking a dwelling place in this world; they call us to free ourselves from the sad burden of ideas which constitute our identity, to detach from, to dispossess and get rid of that kind of “I” who is prey to the burden of time, that time which bears heavily on all of us and hinders everything: wise pieces of advice I would like to carve on this church’s tympanum 28with the help of all the graces from Heaven.

1This essay is the translation of a lecture delivered by the author of this volume at the I International Thomas Merton Conference celebrated at the International Center of Mystical Studies – City of Avila (Spain) in October 2006. It was published in a bilingual edition of the Conference Proceedings entitled Seeds of Hope: Thomas Merton’s Contemplative Message , ed. Fernando Beltran Llavador and Paul M. Pearson (Ávila: Ediciones CISTERCIUM-CIEM, 2006), pp. 61-79.

2Thomas Merton, The Wisdom of the Desert (New York: New Directions, 1960), p. 8.

3 The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton (New York: New Directions, 1977), pp. 319-20. There is a third part to this poem in Collected Poems that is omitted here.

4Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation (New York: New Directions, 1961), p. 295.

5Thomas Merton, The Seven Storey Mountain (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1948), p. 419. According to Virginia Randall, one of the major themes in Merton’s poetry is precisely “the mystery of the Transcendent Self, the No-One who has gone beyond the individual self, and who is, consequently united with all.” Virginia F. Randall, “The Quest for the Transcendent Self: The Buddhist-Christian Merger in Thomas Merton’s Poetry,” Cithara , 17. 1 (November 1977), pp. 17-18.

6Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation , op. cit., p. 55.

7Thomas Merton, Raids on the Unspeakable (New York: New Directions, 1966), pp. 9-23.

8 The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton , op. cit., pp. 19-21.

9See Fernando Beltrán Llavador, La contemplación en la acción (Madrid: San Pablo, 1996), p. 73.

10Michael Mott, The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), pp. xxii– xxiii; 127-128.

11Thomas Merton, The Ascent to Truth (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1951), p. 13.

12Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation , op. cit., p. 37.

13The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton , op. cit., pp. 90-92.

14Thomas Merton, Bread in the Wilderness (New York: New Directions, 1953), p. 83.

15 The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton , op. cit., pp. 40-41.

16Thomas Merton, “Honorable Reader”: Reflections on My Work , ed. Robert E. Daggy (New York: Crossroad, 1989), p. 65.

17Thomas Merton, The Seven Storey Mountain , op. cit., p. 410.

18Sonia Petisco, La poesía de Thomas Merton: creación, crítica y contemplación (Madrid: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2004), [Digital publication] http://biblioteca.ucm.es/tesis/fll/ucm-t27037.pdf.

19 The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton , op. cit., pp. 192-93.

20Described by Merton as “a confrontation of twentieth-century questions” in his journal of these years. Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968), p. vi.

21Poem transcribed by Patrick F. O’Connell in his essay “Sunken Islands: Two and One-Fifth Unpublished Merton Poems,” The Merton Seasonal , Vol. 12, No. 2 (Spring 1987), pp. 6-7. He discovered it in the Curtis Brown Archives of the Friedsam Memorial Library at St. Bonaventure University.

22In one of his books, he had already pointed out: “To say I was born in sin is to say […] I came into existence under a sign of contradiction.” Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation , op. cit., p. 33.

23 The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton , op. cit., pp. 231-232.

Читать дальше