Michael Taillard - Corporate Finance For Dummies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Taillard - Corporate Finance For Dummies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Corporate Finance For Dummies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4.5 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Corporate Finance For Dummies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Corporate Finance For Dummies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Corporate Finance For Dummies,

Corporate Finance For Dummies,

Corporate Finance For Dummies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Corporate Finance For Dummies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Straight-line and unit-of-production depreciation

The easiest type of depreciation to use is called straight-line depreciation. Straight-line depreciation is cumulative, meaning that if you report a value in depreciation for a piece of equipment one year, that same amount gets added to the next year’s depreciation, and so on, until you get rid of the equipment or its value drops to 0.For example, if you buy a piece of equipment for $100 and each year it has a depreciation of $25, then you’d report $25 of accumulated depreciation the first year and $50 of accumulated depreciation the next year, while PPE value would go from $100 the first year to $50 the next.

To calculate straight-line depreciation, all you do is start with the original purchase price of the equipment, subtract the amount you think you can sell it for as scrap, and then divide that number by the total number of years that you estimate the equipment will be functional. The answer you get is the amount of depreciation you need to apply each year. So a piece of equipment bought for $110 that lasts four years and can be sold as scrap for $10 has a depreciation of $25 each year.

To calculate straight-line depreciation, all you do is start with the original purchase price of the equipment, subtract the amount you think you can sell it for as scrap, and then divide that number by the total number of years that you estimate the equipment will be functional. The answer you get is the amount of depreciation you need to apply each year. So a piece of equipment bought for $110 that lasts four years and can be sold as scrap for $10 has a depreciation of $25 each year.

A similar type of depreciation, called unit-of-production depreciation, replaces years of usage with an estimated total number of units that the equipment can produce over its lifetime. You calculate the depreciation each year by using the number of units produced that year.

SUM OF YEARS DEPRECIATION

The sum of years method for calculating depreciation applies a greater value loss at the start of the equipment’s life and slowly decreases the value loss each year. This method allows companies to take into account the marginally decreasing loss of value that most purchases go through.

To see what I mean, imagine that you’re buying a new car. Unless you get into an accident or otherwise damage the vehicle, the car itself will never lose as much value during its lifetime as it does in the first year. By the time the car is 10 years old, it will have lost most of its value, but it won’t be losing its value as quickly each year.

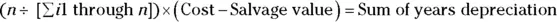

To calculate the depreciation each year by using the sum of years method, you divide the remaining number of years of life the equipment has left, n, by the sum of the integers 1 through n, and then multiply the answer by the cost of the equipment minus salvage cost. Here’s what that looks like in equation form:

To calculate the depreciation each year by using the sum of years method, you divide the remaining number of years of life the equipment has left, n, by the sum of the integers 1 through n, and then multiply the answer by the cost of the equipment minus salvage cost. Here’s what that looks like in equation form:

So if you purchase a piece of equipment for $100,000 and it’s supposed to last for five years with a salvage value of $10,000, then the first year’s depreciation would look like this:

The first year represents  of the total depreciation that the equipment will go through. The next year is

of the total depreciation that the equipment will go through. The next year is  (in this case, $24,000), the next year is

(in this case, $24,000), the next year is  , and so on.

, and so on.

Intangible assets

Intangible assets are things that add value to a company but that don’t actually exist in physical form. Intangible assets primarily include the legal rights to some idea, image, or form. Here are just a few examples:

The big yellow M that McDonald’s uses as its logo is worth quite a bit because people recognize it worldwide. Imagine if McDonald’s simply gave that M, which it calls the “Golden Arches,” away to another restaurant. How much business would it attract?

The curved style of the Coca-Cola bottles, as well as the font of the words Coca-Cola, are worth a lot of money because, like the Golden Arches, they’re easy to recognize across the globe.

For pharmaceutical companies, owning the patent to some new form of medication can be worth quite a lot even if they’re not producing the medicine yet simply because the patent gives them the right to produce that medicine while simultaneously restricting other businesses from producing the same thing.

None of these examples can be physically touched, but they contribute to the value of the company and are certainly considered long-term assets.

Other assets

Any assets that a company hasn’t otherwise listed in the assets portion of the balance sheet go into an all-inclusive portion called other assets. The exact items included can vary quite a bit depending on the industry in which the company operates.

Learning about Liabilities

Liabilities include those accounts and debts that a company must pay back. Like assets, liabilities usually fall into two main categories:

Current liabilities: Liabilities that must be paid back, fully or in part, in less than one year

Long-term liabilities: Liabilities that must be paid back in a time period of one year or more

Current liabilities

This section lists the current liabilities you find on the balance sheet in order from those that must be paid in the shortest period from when they were incurred to those that can be paid off in the longest period from when they were incurred.

Accounts payables

Accounts payables include any money that’s owed for the purchase of goods or services that the company intends to pay within a year. Say, for instance, that a company purchases $500 in paper clips and plans to pay that amount off in six months. The company adds $500 to the value of its accounts payables. But after the company pays an invoice for the money it owes, it removes the value of that invoice from the accounts payables.

Unearned income

When a company receives payment for a product or service but has yet to provide the goods or services it was paid for, the value of what the company owes the customer contributes to its unearned income. Imagine, for example, that you own a dog polishing business that charges $10 per session. One of your customers pays $120 for monthly sessions, so your unearned income for that customer is $120 at the start. That value decreases by $10 every month as you provide the services that the customer paid for in advance.

Accrued compensation and accrued expenses

As a company utilizes resources such as labor, utilities, and the like, it must eventually pay for these resources. However, most companies make such payments once every week, two weeks, three weeks, month, and so on, not upon receipt of the resource.

Accrued compensation refers to the amount of money that employees have earned by working for the company but haven’t been paid yet. Not that the company is refusing to pay, necessarily, just that people tend to get paid once every one to four weeks. So until these people receive their paychecks, the amount that the company owes them is considered a liability.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Corporate Finance For Dummies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Corporate Finance For Dummies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Corporate Finance For Dummies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.