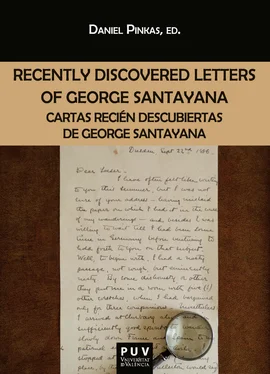

But how did this fine and long-forgotten set of letters come to light again? Like the discovery of penicillin, X-rays or rubber, though admittedly not quite as consequential, locating Santayana ’s letter to Charles Loeser was a matter of serendipity. Following Irving Singer ’s suggestion, who had written that the «Santayana-Cory-Strong triangle» 23(was «almost worthy of Proust or Henry James in its subtlety,» I began searching for Charles A. Strong’s letters to Santayana, so as to gain a fairer appreciation of the (at times acrimonious) philosophical discussions that took place, for decades, between the two old friends. Strong kept Santayana’s letters, which are included in The Letters of George Santayana , but Santayana hardly ever kept any letters addressed to him. Strong, however, took with utmost seriousness his debates with Santayana, so he made copies of some of his letters to his friend.

In the midst of my research, I came across the Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America, hosted on the Frick Collection website. One of the entries indicated that Houghton Library at Harvard had received in 2012 a box of documents labelled «Letters from William James and George Santayana to Charles Alexander Loeser, 1886-1912 and undated.» The entry also mentioned that it was a donation in memory of Charles A. Loeser made by his granddaughter, Philippa Calnan. Given the importance Santayana granted to his friendship with Loeser in his autobiography and the absence of any letters to this recipient in the critical edition of the Santayana’s letters, I knew right away that I had chanced upon something interesting. The librarian I contacted at Houghton Library informed me that the documents had not yet been scanned, but that they could do so quickly. In September 2018, by an amusing coincidence, I was at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence where I had just visited the rooms dedicated to the Loeser bequest, when I received the compressed files of Santayana’s letters to Loeser.

***

To date, we have not been able to ascertain the precise origin of the second batch of letters published in this book. We only know that in 2016 the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University reported that a collection of 60 letters written between 1903 and 1937 by Santayana to Baron Albert Wilhelm Freiherrn von Westenholz, had been added to their George Santayana Papers archive.

Santayana talks about Westenholz (from here onwards I will drop the «von», following Santayana’s practice) in the first chapter of the second part of Persons and Places , titled «Germany». Between 1886 and 1888, Santayana spent two semesters studying in Berlin. After that he made several holiday visits to Germany, the last of which

[he] called a Goethe pilgrimage, because [he] went expressly to Frankfort and to Weimar to visit the home of Goethe’s childhood and that of his old age.[He] was then preparing [his] lectures on Three Philosophical Poets , of whom Goethe was to be one. Even that, however, would probably not have induced me to revisit Germany had I not meantime formed a real friendship with a young German, Baron Albert von Westenholz. 24

The Baron, born in 1879 in Hamburg, was the son of a banker («originally perhaps Jewish») and of the daughter of a Bürgermeister (mayor) of that city («with the most pronounced Hanseatic Lutheran traditions»). 25Westenholz spent his apprenticeship at the London branch of the bank where his father was a partner, and learned to speak English, «perfectly» according to Santayana. However, he was never appointed by the firm, for, as the reader of Santayana’s letters is soon made aware, Westenholz’s mental health «was far from good; he suffered from various forms of mental or half-mental derangement, sleeplessness, and obsessions.» 26

Around 1900, Westenholz turned up at Harvard. Santayana recounts the beginnings of their friendship as follows:

I was then, in 1900-1905, living at No. 60 Brattle Street, and had my walls covered with Arundel prints. 27These were the starting-point of our first warm conversations. I saw at once that he was immensely educated and enthusiastic, and at the same time innocence personified; and he found me sufficiently responsive to his ardent views of history, poetry, religion, and politics. He was very respectful, on account of my age and my professorship; and always continued to call me lieber Professor or Professorchen ; but he would have made a much better professor than I, being far more assiduous in reading up all sorts of subjects and consulting expert authorities. 28

We do not know how long Westenholz stayed at Harvard, nor whether he ever graduated. But after he left Cambridge, Santayana visited him three times in Hamburg, where he met his invalid mother and his older sister Mathilde; the two friends also met in London, Amsterdam and Brussels, but never in Italy, despite Santayana’s numerous attempts to lure Westenholz to a country «where we should have found so many themes for enthusiastic discussion.» 29

Santayana considered Westenholz one of the three best educated persons he had known, 30none of whom, as he remarks, had ever gone to school. He can best be described as a Privatgelehrter (private scholar) who wrote and translated poetry (notably Santayana’s sonnets) and, who, like Loeser, was an avid collector. 31The admiration and affection Santayana expresses towards his German friend in Persons and Places are fully corroborated by the newly found letters, amply confirming the statement with which Santayana begins the section dedicated to this relationship: «Westenholz was one of my truest friends. Personal affection and intellectual sympathies were better balanced and fused between him and me than between me and any other person.» 32In passing, they provide a stinging rebuttal to Bertrand Russell’s impression that Santayana was «a cold fish». 33The tone of Santayana’s letters is uniformly affectionate, sometimes confessional, with frequent and delightful humorous touches. Santayana’s concern for the Baron’s mental condition is a recurring theme, which he addresses with profound empathy and admirable tact. The topics range freely from personal, occasionally intimate, matters to extensive and always lively discussions of philosophy, religion, culture, politics and literature. This is one of those cases where one can only regret not having at one’s disposal the letters that make up the other half of the correspondence.

There is no better way, I believe, to get a sense of Westenholz’s torments and personal qualities than to read the last two paragraphs devoted to him in Persons and Places , respectively titled «His obsessions» and «His unclouded intelligence»:

As for him, his impediments were growing upon him. Fear of noise kept him awake, lest some sound should awake him; and he carried great thick curtains in his luggage to hang up on the windows and doors of his hotel bedrooms. At Volksdorf, his country hermitage, the floors were all covered with rubber matting, to deaden the footfalls of possible guests; and he would run down repeatedly, after having gone to bed, to make sure that he had locked the piano: because otherwise a burglar might come in and wake him up by sitting down to play on it! When I suggested that he might get over this absurd idea by simply defying it, and repeating to himself how utterly absurd it was, he admitted that he might succeed in overcoming it; but then he would develop some other obsession instead. It was hopeless: and all his intelligence and all his doctors and psychiatrists were not able to cure him. In his last days, as his friend Reichhardt told me, the great obsession regarded bedding: he would spend half the night arranging and rearranging mattresses, pillows, blankets and sheets, for fear that he might not be able to sleep comfortably. And if ever he forgot this terrible problem, his mind would run over the more real and no less haunting difficulties involved in money-matters. The curse was not that he lacked money, but that he had it, and must give an account of it to the government as well as to God. And there were endless complications; for he was legally a Swiss citizen, and had funds in Switzerland, partly declared and partly secret, on which to pay taxes both in Switzerland and in Germany; and for years he had the burden of the house and park in Hamburg, gradually requisitioned by the city government, until finally he got rid of them, and went to live far north, in Holstein, with thoughts of perhaps migrating to Denmark. A nest of difficulties, a swarm of insoluble problems making life hideous, without counting the gnawing worm of religious uncertainty and scientific confusion.

Читать дальше