The publication of the critical edition was preceded by the publication, in 1955, of about 250 letters that Santayana’s friend and secretary, Daniel Cory, had managed to assemble. In order to locate these letters, Cory published advertisements in leading journals and reviews, he visited the main libraries housing Santayana’s manuscript materials and he wrote to people he thought had been his correspondents. As he undertook this task, he was, as he recounts in the foreword, «a prey to certain misgivings». First, the sheer size of the correspondence of someone who had been an established writer for over sixty years would probably turn out to be forbidding. Secondly,

Santayana was such an accomplished artist in so many fields […] that I wondered if in the more spontaneous rôle of correspondent he might fall short of the very high standard he had always set himself. I knew that he had never sent anything to his publisher in an untidy condition, but always dressed for a public appearance. Above all, I did not want his friends or critics or general audience to say of him what has unfortunately been said of other distinguished writers: What a pity his letters were ever published! 3

But as he started receiving letters, Cory’s anxieties were mostly assuaged. Admittedly, the volume of correspondence would be enormous, and everything would have to be sorted in order to eliminate «polite» or banal letters. On the other issues, however, there was nothing to worry about. As Cory wrote: «this large collection of letters soon proved a fresh and exciting adventure. They are essential as a revelation of his life and mind, and a further confirmation of his literary power.» 4

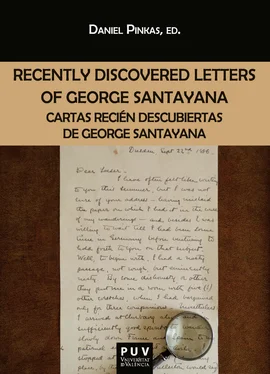

Although the critical edition of The Letters of George Santayana aimed painstakingly at comprehensiveness (the editors sent letters of inquiry to sixty-three institutions reported as holding Santayana manuscripts, they ran advertisements in leading literary publications and contacted more than fifty individuals who were potential recipients of Santayana’s letters, and as a result were able to add over two thousand more letters to Cory’s initial set of about a thousand) the ideal of absolute completeness was clearly out of reach: not only because, as we know, Santayana himself destroyed his letters to his mother, but because the editors were unable to locate many letters whose existence could be inferred from Santayana’s or his correspondents’ allusions. Thus, at the end of the editorial appendix of the critical edition, there is a «List of Unlocated Letters» comprising almost one hundred entries. It should be noted that these unlocated letters do not include those, recently discovered, which we are pleased to present in this volume.

The editors of the critical edition of the Letters , however, did mention that none of Santayana’s letters to von Westenholz had been located, just as they comment on the relative scarcity of letters (only six) to John Francis Stanley («Frank»), the second Earl Russell, given the significance of this relationship to Santayana 5. In retrospect, therefore, the absence of any letters addressed to Charles Loeser and Baron Albert von Westenholz in the critical edition points unequivocally to the possibility that such letters could exist somewhere. These are two persons to whom Santayana devoted several pages in his autobiography, leaving no doubt as to how much they had meant to him. Let us begin with Charles Loeser.

At the beginning of chapter XV («College Friends») of Persons and Places , Santayana recounts his first meeting with Loeser, at Harvard, in a passage that deserves to be quoted in full:

First in time, and very important, was my friendship with Charles Loeser. I came upon him by accident in another man’s room, and he immediately took me into his own, which was next door, to show me his books and pictures. Pictures and books! That strikes the keynote to our companionship. At once I found that he spoke French well, and German presumably better, since if hurt he would swear in German. He had been at a good international school in Switzerland. He at once told me that he was a Jew, a rare and blessed frankness that cleared away a thousand pitfalls and insincerities. What a privilege there is in that distinction and in that misfortune! If the Jews were not worldly it would raise them above the world; but most of them squirm and fawn and wish to pass for ordinary Christians or ordinary atheists. Not so Loeser: he had no ambition to manage things for other people, or to worm himself into fashionable society. His father was the proprietor of a vast «dry-goods store» in Brooklyn, and rich—how rich I never knew, but rich enough and generous enough for his son always to have plenty of money and not to think of a profitable profession. Another blessed simplification, rarely avowed in America. There was a commercial presumption that man is useless unless he makes money, and no vocation, only bad health, could excuse the son of a millionaire for not at least pretending to have an office or a studio. Loeser seemed unaware of this social duty. He showed me the nice books and pictures that he had already collected—the beginnings of that passion for possessing and even stroking objets-d’art that made the most unclouded joy of his life. Here was fresh subject-matter and fresh information for my starved aestheticism—starved sensuously and not supported by much reading: for this was in my Freshman year, before my first return to Europe. 6

The question of whether, or to what extent, this paragraph is redolent of antisemitism has been discussed at length by John McCormick in his biography of Santayana 7, and I propose to leave it aside 8, in order to concentrate on «the keynote» of the Santayana and Loeser connexion: «pictures and books». Indeed, Loeser immediately became for Santayana a mentor in the field of art appreciation, and later showed him Italy, in particular Rome and Venice, and «initiated [him] into Italian ways, present and past», making Santayana’s life in the country where he chose to reside from the 1920s onwards «richer than it would have been otherwise» 9. Even in his early college years, Loeser was, in a small way, what he later became on an international scale: a refined and shrewd art collector. Santayana readily admits that «Loeser had a tremendous advance on [him] in these matters, which he maintained through life: he seemed to have seen everything, to have read everything, and to speak every language» 10A comparison with the eminent art critic Bernard Berenson (who was also Jewish but converted twice), whom Santayana later frequented, immediately springs to Santayana’s mind: Berenson enjoyed the same cultural advantages, and soon gained a public reputation through his writings, which Loeser never did. But the comparison is not at all favorable to Berenson: Loeser, says Santayana, had a sincere love for his favorite subject (the Italian Renaissance) while Berenson was content to merely display it.

Wealth was another big advantage that Loeser had over Santayana. During their early university years, when the two friends went to the theater or the opera in Boston, it was Loeser who inevitably paid; and when, later, they traveled together in Italy, Santayana would contribute a fixed (and modest) daily sum to their expenses, leaving Loeser, who spoke the language, to make the arrangements and pay the bills. Loeser untied the purse with as few qualms as Santayana had in accepting this generosity, because «it was simply a question of making possible little plans that pleased us but that were beyond my unaided means.» 11

Aside from a common interest in «books and pictures», one of the factors that obviously brought the two young students together was their status as outsiders, due to their religious origins, respectively Catholic and Jewish, in an overwhelmingly Protestant institution. For Santayana, this marginal status was somewhat compensated by his association, through his mother’s first marriage, with one of Boston’s prominent Brahmin families. But not only was Loeser unashamedly Jewish, his father owned a «dry-goods store», two facts that «cut him off, in democratic America, from the ruling society.» 12This seemed strange to Santayana, considering how much more cultivated his friend was than «the leaders of undergraduate fashion or athletics.» 13A somewhat ambivalent portrait follows this remark about Loeser’s isolation at Harvard:

Читать дальше