BIBLIOTECA JAVIER COY D’ESTUDIS NORD-AMERICANS

https://puv.uv.es/biblioteca-javier-coy-destudis-nord-americans.html

DIRECTORA

Carme Manuel

(Universitat de València)

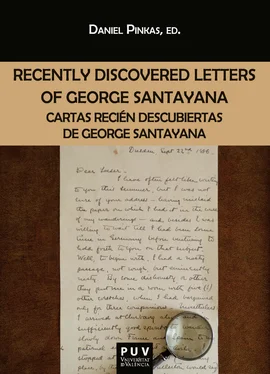

Recently Discovered Letters of George Santayana

Cartas recién descubiertas de George Santayana

© Edición bilingüe.

Edición e introducción de Daniel Pinkas,

traducción y notas de Daniel Moreno Moreno,

presentación de José Beltrán

1ª edición de 2021

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-9134-905-1 (papel)

ISBN: 978-84-9134-906-8 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-84-9134-907-5 (PDF)

Imagen de la cubierta: Adrián Beltrán Marín

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

https://puv.uv.es

publicacions@uv.es

Edición digital

Presentation

Presentación

José Beltrán Llavador

Introduction

Introducción

Daniel Pinkas

Letters to Charles A. Loeser (1864-1928)

Cartas a Charles A. Loeser

Letters to Albert W. von Westenholz (1879-1939)

Cartas a Albert W. von Westenholz

José Beltrán Llavador

How stimulating it is to delve into this written exchange between George Santayana and two of his many friends over five long decades spanning the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The newly discovered letters constitute a small collection compared to the totality of his epistolary activity, which occupies no less than eight books (of volume V) in the Works of George Santayana that the MIT Press has been publishing with exquisite scholarly care. Thus the values of the unexpected, the unusual and the unpublished are added to the gift of the discovery itself: who would have thought that it would still be possible to find new material with which to enrich such an extensive corpus?

In these letters, which are now published and translated for the first time, the most characteristic features of the thinker and the human being are distilled. They mirror and reflect a life told as it is lived, and they simultaneously confirm an endless narrative apprenticeship and negate a way of doing philosophy that is alien to everyday life. They show, instead, life accompanied by its narrative, indeed intensified and conjured up by the constant exercise of writing. And now we have the privileged opportunity to look once again, with the help of materials that provide new vistas, into the fascinating life of reason unfolded by the universal thinker and citizen of the world George Santayana.

The origin of these letters can be traced back to the time when Santayana was a very young student at Harvard, aged 23, and they end when he reached 74, once he had already completed most of his work and was settled definitively in Rome. In terms of chronology, the first group of letters (27), addressed to Charles A. Loeser, began in September 1886 and continued until Santayana’s definitive departure from the United States in October 1912; the second, more extensive (61), addressed to Baron Albert von Westenholz, began at the turn of the century, in July 1903, and concluded in January 1937, fifteen years before Santayana’s death in Rome. Neither of these two singular friends were anonymous figures. Both form part of a certain social lineage and, in spite of their different profiles, the two of them embody a tradition and a cultural heritage to whose distinctive mark Santayana, rather than a direct participant, was a sensitive, receptive and detached witness, as we shall see in not a few of his missives.

If the reading of this constellation of letters is stimulating for many reasons, the account of their discovery in the “Introduction” by Daniel Pinkas is fascinating. Daniel Pinkas is not only a most attentive and insightful reader of Santayana but an internationally renowned researcher who has devoted a significant part of his scholarly interests to the analysis and interpretation of the philosopher’s work.

Pinkas’ recent discovery of these letters, now published for the first time in English and in Spanish, is a testimony to his dedication and perseverance. As in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Stolen Letter”, Santayana’s letters can be said to have been there for anyone who wanted to see them. Even if the facts are as Pinkas himself describes them, things are not that simple, and it would be unfair to downplay his astonishing discovery. First, it was necessary to know that these letters existed and to feel intrigued by their absence from the volumes devoted to Santayana’s correspondence in the MIT edition of his collected works. Then, what was also needed was to know how to decipher the signs pointing to the place where they were kept. Daniel Pinkas modestly attributes this wonderful finding to a combination of coincidence and causality, or chance and necessity, which he sums up as a result of serendipity. Even if this were so, it is worth remembering that this fortunate concurrence of events was preceded by much previous research and excellent documentation work, for only with constant and conscious attention is it possible to keep track and establish the right connections, which are the preconditions for being at the right place at the right time.

On the other hand, the fact that the Frick Collection website records the existence of Loeser’s correspondence and that the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University also records the acquisition of Westenholz’s letters five years ago, has a noteworthy symbolic significance. I had the opportunity to visit the Frick Collection in 2014 during a stay of just over a week in the Big Apple where I was able not only to breathe the spirit of an era but also to experience the fruits of its unique attitude, that rare disposition that combines art and enterprise, pragmatism and altruism, tradition and modernity.

Both the Columbia University Libraries, which lodge 12 million copies, and the Frick Collection , which holds an impressive artistic and cultural heritage, reveal that the history of the United States is comparatively recent, and perhaps that is why institutions such as these treasure every trace or vestige, and every testimonial document that can contribute to recreating and enriching the foundational stories of its past and the prophetic accounts of its future.

Thus, in these letters we find, threading their narrative, a sort of surprising patchwork, a microcosm filled with forms of life pulsating in each message, within every word, with highly suggestive echoes in resonance with the rest of the thinker’s work. The epistolary genre, as cultivated by Santayana and his contemporaries, is less and less frequent, yet another social practice that is being lost, swept away by the speed and formats of the digital media. For this very reason, these handwritten letters now have the added value of being approached as ethno-texts, noble and unique remains of an anachronistic genre.

On the other hand, Santayana’s letters partake in a rich conversation where profound reflections are intermingled with everyday matters and where a plethora of interests and a plurality of perspectives inhabit the very space they shape. Here we can clearly perceive the deep thinker and the human being, the lucidity of the former and the frailties of the latter, the chiaroscuros that Santayana himself detects in his own persona and to which he applies an enormous capacity for humour, irony and self-criticism.

Читать дальше