3A. Maslow, Motivation and Personality (New York: Harper and Row, 1954)

4Frederick Herzberg, Work and Nature of Man (New York: Crowell, 1966). The theory had already been suggested in Herzberg, Mausner and Snyderman, The Motivation to Work (New York: Wiley, 1959)

5D. McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise (New York: McGraw Hill, 1960)

6D. McGregor, Leadership and Motivation (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1966), pp. 259 ff.

CHAPTER 3

THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORY OF MOTIVATION

Introduction

In McGregor's view, motivation to perform an action is the result of the search for both the extrinsic consequences of the action (incentives that “someone else” has attached to that action) and the intrinsic consequences that follow from the performance itself of the action. For McGregor, the factors that intrinsically motivate the performance of a task are properties of a human system and represent potential strength not present in mechanical systems. We will now explore what this “potential strength” may consist of.

One of our first observations is that when a person interacts with others, his action has different types of results or consequences. Each of these may constitute a powerful source of motivation, that is, each may be directly sought by the person who acts, and, consequently, may serve as a motive to perform the action.

However, a person may well perform the action seeking i only one, or a few, of these results. Obviously, this will not mean that he does not obtain the other results as well. It is precisely for this reason that we must introduce the notion of the correctness of an action plan. We call an action plan correct only when the consequences that have not been directly sought by the decision-maker do not entail unsought consequences that create a new problem more serious than the one solved by the implementation of the plan.

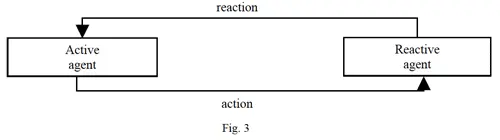

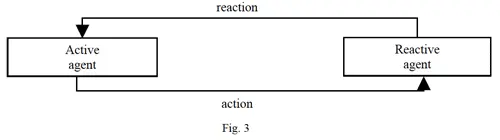

All the possible results of the implementation of an action plan can be synthesized into three categories or types, all irreducible to one another. In order to see why this is so, and to identify the results which correspond to each of these categories, one need only observe that we can conceive of human action as a process of interaction (action and reaction) with an environment which, in general, will also be human (that is, made up of other people). The schematic conceptualization of this interaction is shown in Fig. 3.

Motives of individual actions

The first feature of personal agents who interact with each other is that, in general terms, they can learn as a result of experiences they have in the course of their interactions. That is, if both the active agent's action and the reactive agent's reaction are produced by the decision each one has made at a particular time, their experiences may, and probably will, lead them to conclude that they will have to modify their decisions in the next interaction.

For example, if the active agent has delivered a certain product (action) to the reactive agent, obtaining something else in return (reaction) from him, the experience both agents have had during the interchange may have consequences from the perspective of their possible future interactions. It may have caused a change of attitude so that either agent no longer wishes to repeat the interaction under any circumstances (he thinks he has been cheated by the other), or there is mutual growth in the interest in continued interaction. In reality, almost the only possibility we could exclude a priori is that the relationship between the two agents would not change at all as a consequence of the experiences they have had in the interaction.

Learning is what we will call any change that occurs within the persons who have interacted as a result of the experiences they have had while interacting, provided that that change insignificant for explaining future interactions.

Decision rule is what we will call the set of operations—whatever they may be—by which an active agent chooses his action (or a reactive agent his reaction). In this case, learning is the concept we use to express the changes in the respective decision rules that have resulted from the interaction. Therefore, in order to talk about all the consequences produced by the performance of an action by the active agent, we must distinguish between three types of consequences or results of that action:

Extrinsic results: the interaction itself

Internal results: learning of the active agent.

External results: learning of the reactive agent.

An active agent implements action plans to solve his problems, that is, to achieve satisfactions. The satisfaction achieved by the implementation of an action plan we will call the effectiveness of that action plan. That is, the degree of effectiveness of an action plan is equivalent to the degree of satisfaction achieved by the person as a result of performing it and, consequently, expresses the value of the extrinsic results produced by the plan for the active agent.

The efficiency of an action plan will mean the changes that the learning brings about in the active agent, in so far these changes affect future satisfactions achievable by this agent through his interactions with the same reactive agent. The efficiency of a plan expresses the value of the internal results achieved by the performance of the plan for the active agent.

The consistency of an action plan will mean the changes that learning brings about in the reactive agent when these changes affect the future satisfactions achievable by him through interactions with that reactive agent. A plan's consistency therefore expresses the value for the active agent of the external results achieved by the performance of the plan.

The framework we have used to analyze the consequences of a person's action when he interacts with others immediately reveals the existence of two types of consequences we have included within the efficiency and consistency of an action plan: these express what people learn by interacting with each other. This learning may have considerable value for the active agent, that is, it may significantly influence his achievement of future satisfactions. It is therefore not surprising that the achievement of this learning may be an explicit objective of the decisions a person makes.

As we have said previously, it may also happen that both types of learning are not sought but rather ignored when making decisions. Obviously, the interaction will produce the corresponding changes, irrespective of whether the decision-maker wants them. Later, if it turns out that the changes do not satisfy him, his decision will have been incorrect.

The attainment of any of these three types of results, or of all of them at once, may be a motive for a person's decisions—that is, it may be an achievement explicitly aimed at by him in his decisions. There are therefore three types of motives for personal action:

Extrinsic motives: those aspects of reality that produce satisfactions experienced as a result of an interaction.

Intrinsic motives: those aspects of reality that cause achievements at the level of the decisionmaker's learning.

Transcendent motives: those aspects of reality that bring about the achievement of learning by the other people with whom the decision-maker interacts.

It is obvious that one's own learning is a powerful driving force for human actions. However, the inclusion of other people's learning as a possible motive for action may seem somewhat surprising.

Examples of these motives in human action abound. It is not uncommon to find people who generously devote their efforts to helping others. A keen observer will even readily find traces of what we have called transcendent motives underlying most human decisions. Pure selfishness is probably as rare as pure altruism. Some deeply buried instinct warns us, and rightly so, that it is impossible to achieve stable relationships between human beings if one completely ignores the consequences that one's actions have for other people.

Читать дальше