For most malocclusions, quality treatment is best provided by the use of one or other of the recognized fixed appliance treatment techniques. If the dental arches are correctly related and adequate space is present, then the teeth are initially ‘levelled’ to a labial archwire of standardized archform and a given coefficient of elasticity. Later, heavier round or rectangular steel archwires are substituted to activate root movements that will pave the way to achieving an optimal result. In cases of incorrectly related dental arches, the use of other appliances is recommended, such as headgear, functional appliances or intermaxillary means of traction, prior to or together with the fixed appliances. Here, space may be provided by the extraction of teeth or by lengthening the arches mesio‐distally or expanding them laterally.

When dealing with a malocclusion that incorporates an impacted tooth, this procedure will need to be modified. Unlike other teeth in the mouth, the impacted tooth may be severely displaced from its normal position in all three planes of space, and much anchorage will be expended in bringing it into alignment. Accordingly, a rigid anchor base must be developed against which to pit the forces required to resolve the impaction.

At the age at which an impacted maxillary canine is treated, the full permanent dentition (with the exception of third molars) is usually present. Accordingly, a fully multibracketed appliance would normally be placed in position. With the use of light archwires, the entire dentition will be treated through the stages of levelling and the opening of adequate space in the arch for the impacted tooth. A heavy and more rigid archwire is then placed into the brackets on all the teeth of the fully aligned and complete dental arch. The aim of this is to provide a solid anchorage base [5, 6], which will not allow the distortion that may otherwise result from the forces that will eventually be applied to the impacted tooth after its exposure. One should not underestimate the demands made on the anchor unit by forces designed to resolve a grossly displaced canine, particularly if the forces are applied for an extended duration.

By contrast, at the age at which an impacted upper central incisor needs to be treated, only first permanent molars and three permanent incisor teeth are present in the maxillary arch. Accordingly, in order not to compromise the remainder of the dentition, it will be necessary to employ alternative means of making the appliance system rigid in order to oppose the light forces that will be applied to the impacted tooth. The anchorage value of the appliance may be enhanced by including a soldered transpalatal bar or by bonding brackets to the deciduous molars and canines.

Some form of attachment must be placed on the tooth in order to be able to influence its positive resolution and to bring it into its place in the dental arch. These attachments have changed over the years, reflecting the advances made in the field of dental materials.

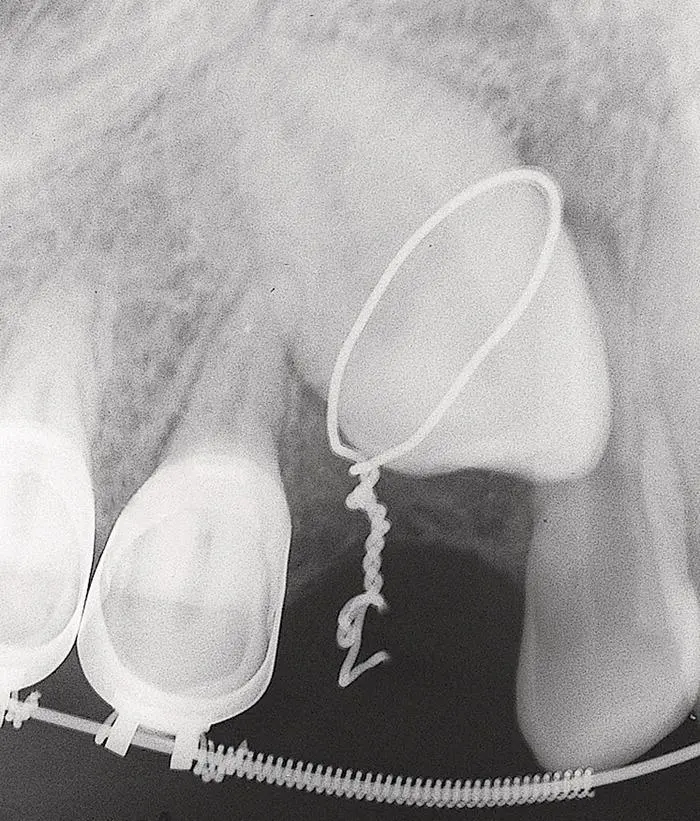

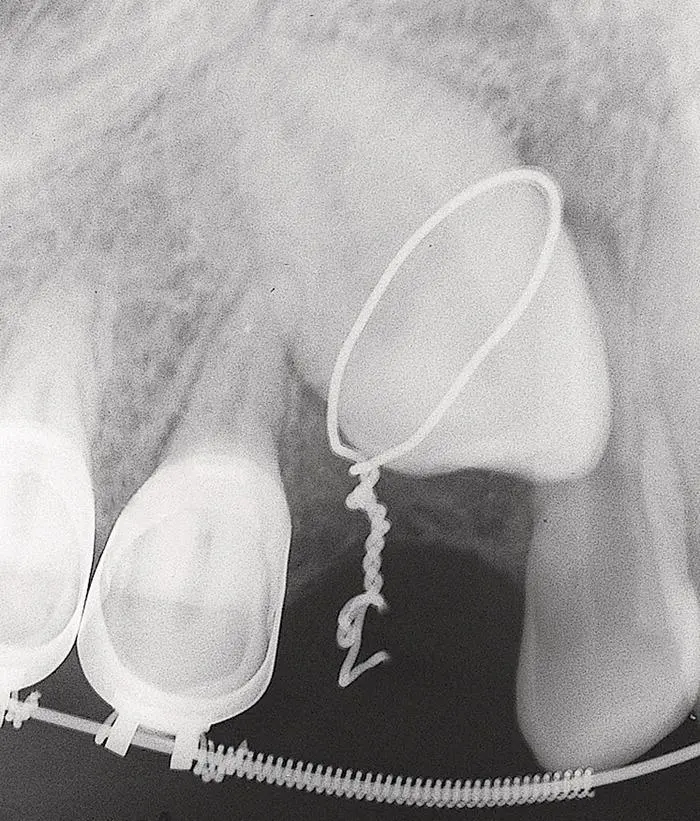

In the years prior to the mid‐1960s, a lasso wire ( Figure 2.1), twisted tightly around the neck of the canine, was widely employed, and indeed was the type of attachment that we ourselves used in our very earliest cases. It will be readily appreciated that the shape of the crown of a normally shaped healthy tooth is such that its narrowest waist diameter is at the cemento‐enamel junction (CEJ). This is where the lasso wire will inevitably settle. This undesirable consequence will unavoidably result in irritation and recession of the gingival and periodontal tissues and will actively prevent their reattachment in this vital area. There is also evidence that, as a consequence of employing this method, external resorption and ankylosis have been produced in the area of the CEJ [7]. The excellent alternatives that are available today have rendered the lasso wire obsolete.

Fig. 2.1 Lasso wire encircling the neck of an impacted canine (circa 1971).

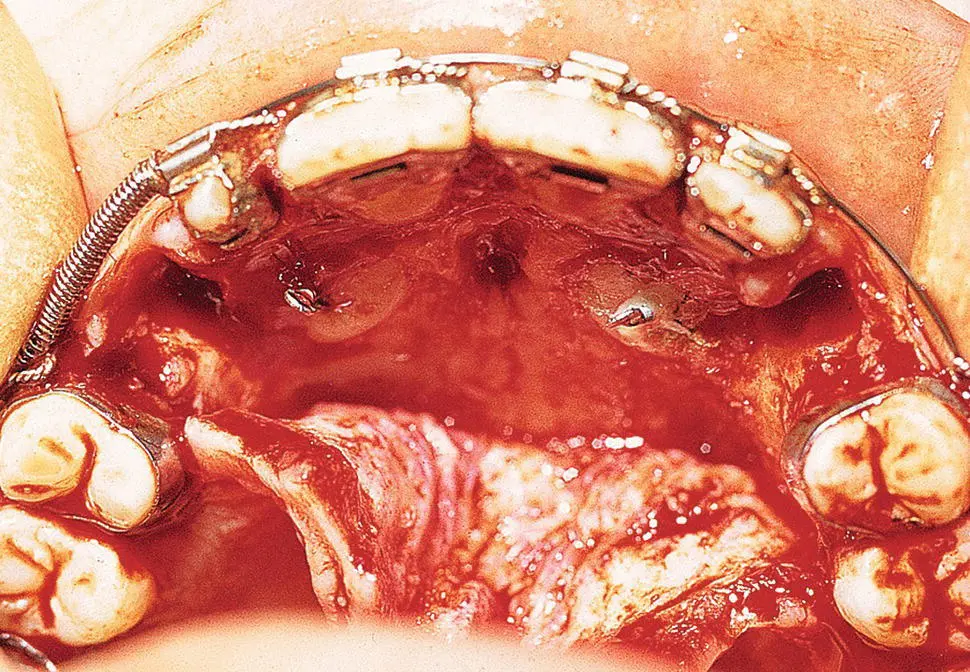

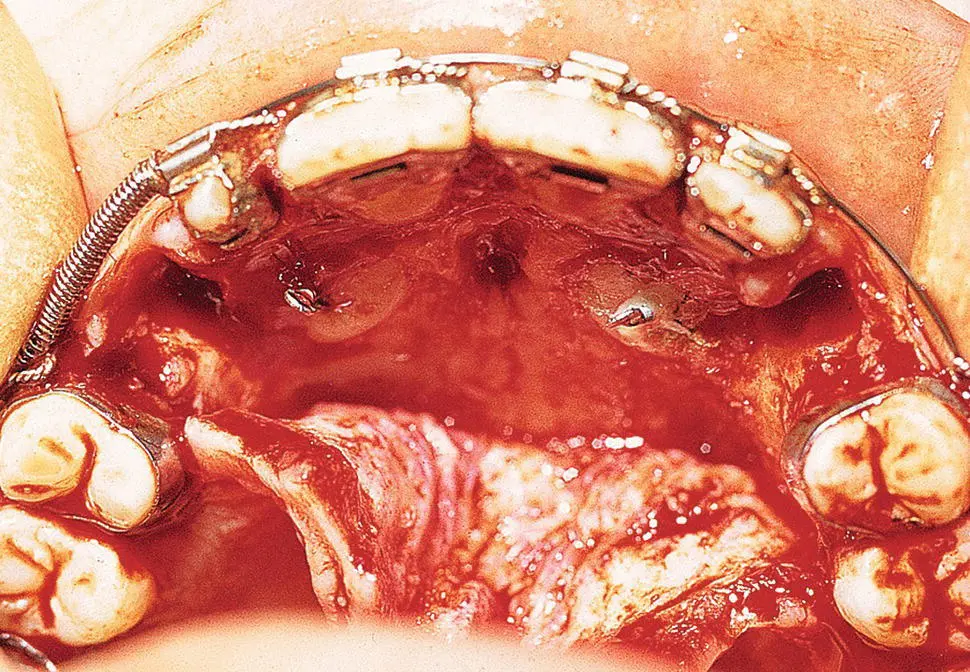

Fig. 2.2 Threaded pins set into prepared holes, drilled and tapped into the enamel and dentine of the surgically exposed canines (circa 1973).

Several systems of threaded pins ( Figure 2.2) have been available for many years. Their original specific purpose was to provide retention for an amalgam or composite core and to allow the provision of a cast crown in a severely broken‐down tooth. However, these threaded pins have also been used in the past as the attachment for an impacted tooth [8, 9], although they have now been totally superseded by other methods of attachment. Some of the disadvantages of the threaded pins method include the fact that it is dentally invasive, necessitating subsequent restoration. Given the difficulties of access to many impacted teeth and the desirability of limiting surgical exposure as much as possible, it may be difficult to determine the orientation of the long axis of the tooth and the drilled hole may inadvertently enter the pulp. Moreover, unerupted and non‐functional teeth often have large pulp chambers. Even in the most favourable of circumstances, it seems that this unnecessarily aggressive method actually causes damage to a virgin tooth, in light of the fact that there are eminently suitable, non‐invasive methods and efficacious alternatives, as we shall discuss below. Nevertheless, the method was still in use and apparently recommended as late as 2004, which was, anachronistically, well into the present era of composite bonded attachments [8, 9].

Preformed orthodontic bands with welded attachments [10] largely replaced both the lasso wire and the threaded pin in our protocol. Clinical experience with these bands showed them to be considerably more compatible with ensuring the health of the periodontal tissues. As with the lasso wire, the use of a band dictated a very wide surgical clearance of tissue on all sides of the tooth. However, in order to permit the introduction and cementation of the band, it was imperative, at the time of placement, to adequately control haemorrhage around the crown and to avoid contamination from oozing blood inside the cement‐filled band.

With the introduction of acid‐etch composite enamel bonding, all the above‐mentioned methods became obsolete. The adoption of the acid‐etch composite bonding technique to the crown of a tooth has many advantages [11–15], most notably in terms of simplicity and reliability of the bond [14]. However, its greatest advantage is that, to be successful, it requires relatively little exposed surface of enamel, a fact that has contributed much to the subsequent periodontal health of the treated result. It is presently without doubt the method of choice from almost every point of view, and is appropriate to replace other methods in virtually all circumstances.

Standard orthodontic brackets

The points to be considered when choosing the type of attachment to be placed on impacted teeth are different for the impacted tooth than those relating to an erupted tooth that needs to be brought into its position in the dental arch. The wide array of orthodontic brackets, advertised in the catalogues of the various orthodontic manufacturing companies, represents sophisticated designs of attachment, which will enable the orthodontist to perform any direction of movement on a tooth in all three planes of space. Since many, or perhaps most, impacted teeth require a wide variety of movements, it would seem logical to place a sophisticated orthodontic bracket on the affected tooth from the outset.

Читать дальше