In my efforts to produce a readable and understandable narrative, I managed to persuade my brother Laurence (Shmuel) Becker to be responsible for the editing and proofreading of this work. He is a lawyer and is the first to admit that he knows absolutely nothing about orthodontics. His theory was that if he could understand what I have written in this volume and could follow the ideas and the logical sequence, then any orthodontist should be able to read, follow and understand the text and the ideas that I have tried to portray easily and painlessly. And so he has corrected, amended, shuffled words around, relocated sections and substituted my words for others that only a lawyer can produce. (He is probably the only other person who will have read the entire book at least five times over.) For all this, I am greatly in his debt.

The wondrous workings of today’s desktop computers have provided me with the means to write this text, which would never have been possible using the steam‐propelled typewriter. However, my computer has also given me a false sense of security, learned from bitter experience. Many times in the past three years I lost material that I had spent days writing, either because I had failed to save it or because I had ‘copy‐pasted’ these sections into other files, which I promptly and unintentionally deleted. I cannot count the number of times that I called my son‐in‐law, Asher Cohen (also a lawyer), setting him the task of rediscovering them and putting me back into the business of writing. He found them every time, at break‐neck speed. I salute his alacrity and his digital skills!

I closely identify with the legendary Danish pianist and comedian who, at the same advanced age as I am now, was still appearing on stage before large live audiences. At the end of one of his solo performances, Victor Borge acknowledged: ‘I wish to thank my parents for having made this possible and I wish to thank my children for having made it necessary.’

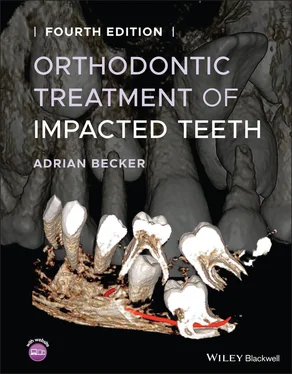

Adrian Becker

Jerusalem, Israel

June 2021

About the Companion Website

This book is accompanied by a companion website.

www.wiley.com/go/becker/orthodontic_treatment_impacted_teeth

The website includes a series of Power Point presentations mainly of CBCT interpretation work‐ups and particularly in relation to diagnosis of impacted teeth. They contain embedded video clips illustrating methods for refining accurate positional identification or analysis of the teeth in 3D and in improving the qualitative recognition of pathologic entities.

Each online resource is called out in the text by number for ease of location.

View all animations in full screen by clicking the square button under the bar at the bottom right of the animation window.

1 General Principles Related to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Impacted Teeth

Adrian Becker

Dental age

Assessing dental age in the clinical setting – the Jerusalem method

When is a tooth considered to be impacted?

Impacted teeth and local space loss

Whose problem?

The timing of the surgical intervention

Patient motivation and the orthodontic option

In order for us to understand what an impacted tooth is and whether and when it should be treated, we must first define our perception of normal development of the dentition as a whole and the time‐frame within which it operates.

The development of a child has many components. In assessing the developmental age of a child, it is necessary to consider and correlate these components and there is a hypothetical mean for each, though the overall development rate rarely falls exactly on this mean. A child’s growth and development rate may also be different for each of the developmental components.

Somatic age: A child may be tall for his or her age, so that his or her somatic age may be considered to be advanced.

Skeletal age: By studying radiographs of the progress of ossification of the epiphyseal cartilages of the bones in the hands of a young patient (the carpal index) and comparing this with average data values for children of his or her age, we are in a position to assess the child’s skeletal age.

Sexual maturation age: The sexual age of a child is related to the appearance of primary and secondary sexual features.

Mental age: This is assessed by intelligence quotient (IQ) tests.

Behavioural age: This is an assessment of a child’s behaviour and his or her self‐concept.

These are among the indices complementing the chronological age , which is calculated directly from the date registered on the child’s birth certificate. All these parameters are essential in the comprehensive assessment of a child’s developmental progress.

Dental age is another of these parameters and is a particularly relevant and important assessment used in advising as to the timing of proper orthodontic treatment. The tables and diagrammatic charts presented by Schour and Massler [1], Moorrees et al. [2, 3], Nolla [4], Demirjian et al. [5], Koyoumdjisky‐Kaye et al. [6], Willems et al. [7] and Liversidge et al. [8] demonstrate the stages of development of the teeth, from initiation of the calcification process through to the completion of the root apex and the average chronological ages at which each stage occurs. Normal and healthy tooth buds develop from initial calcification to root apex closure at a given rate for each of the teeth groupings. That is to say that incisors, canines, premolars, first, second and third molars, in the mandible and in the maxilla, differentiated between males and females, all have their individual specific time at which they reach the various developmental stages. These stages are empirically defined in the above classic works. Schour and Massler [1] produced an atlas from intra utero to adulthood, consisting of 21 consecutive drawings, which feature annual development schemes up to age 12 as well as 3 more schemes up to age 35 years. Nolla [4], on the other hand, used a radiographic assessment of tooth development at 10 different developmental stages, starting from the presence of the crypt through to root apex closure (apexification).

Estimating the stage of development based on the eruption time of teeth is an unreliable method of assessing dental age. Although eruption of each of the various groups of teeth normally occurs at a particular time (when there is half to two‐thirds of the final root length), nevertheless this may be influenced by local factors, which may cause premature or delayed eruption with a wide time‐span discrepancy. This may be true even when root development may be proceeding unhindered.

In contrast, examination of periapical or panoramic X‐rays is a far more accurate tool for dental age assessment. With few exceptions, mainly related to frank pathology, root development proceeds in a fairly constant manner and usually regardless of tooth eruption or the fate of the deciduous predecessor.

Let us take the case of a child of 11–12 years of age who has four erupted first permanent molars and only the permanent incisors, with deciduous canines and molars completing the erupted dentition. If practitioners were to refer only to the eruption chart, they would note that at this age all the permanent canines and premolars should have erupted. They may then conclude that the 12 deciduous teeth had been retained beyond their due time. The treatment that would appear to be the logical sequel to this observation would be the elective extraction of all the deciduous teeth!

Читать дальше