When communicating verbally there are other factors to consider. VAPER can help us to reflect on our communication in the moment and adjust accordingly (Nelson‐Jones 2014).

If you are not fully following the message it is acceptable to ask for clarification. Table 3.2provides examples of clarification questions.

Procedure: Non‐verbal Communication

Non‐verbal communication involves body language, our gestures, and dress (e.g. uniform), and can also be impacted by our height, gender, and scent, which some may find intimidating.

As healthcare professionals work in closer proximity than is socially comfortable we need to be aware of our non‐verbal communication and utilise this method of communication to demonstrate our care and compassion.

Egan's acronym SOLER (Egan 2014) can be a useful tool to use initially to build rapport ( Table 3.3).

Communication is often split into three Cs, represented as 55/38/7 (Mehrabian 1972): 55% of communication occurs through body language, 33% through tone of voice, and 7% through the actual words said. Although this is often contested, it is certainly worth considering when engaged in communication.

In some instances, therapeutic use of silence is also required, allowing the person time to express their message.

Written communication can be used where there is an impairment impacting on the verbal message being received.

It can also be used when professionals need to communicate with each other, i.e. via emails or in multidisciplinary notes.

Written communication needs to be clear, concise, and legible. The key points need to be emphasised, jargon must be avoided, and the patient needs to be comfortable with, and able to use, this method.

New dysphasia or dysarthria.

New or sudden onset of confusion.

Decrease in level of consciousness.

Changes in behaviour following injury.

1 Egan, G. (2014). The Skilled Helper: A Problem Management and Opportunity Development Approach to Helping, 10e. California: Brooks‐Cole.

2 Gates, B., Ellis, R.B., and Kenworthy, N. (2003). Interpersonal Communication in Nursing: Theory and Practice, 2e. Churchill Livingstone.

3 Mehrabian, A. (1972). Nonverbal Communication. Chicago: Aldine‐Atherton.

4 Nelson‐Jones, R. (2014). Nelson‐Jones' Theory and Practice of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 6e. London: Sage Publications.

5 Nursing & Midwifery Council (2018). Standards for Competence for Registered Nurses. London: Nursing & Midwifery Council.

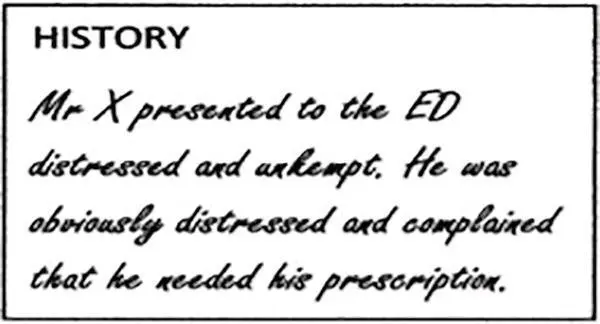

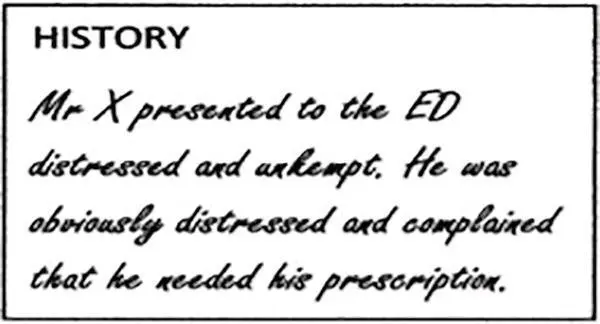

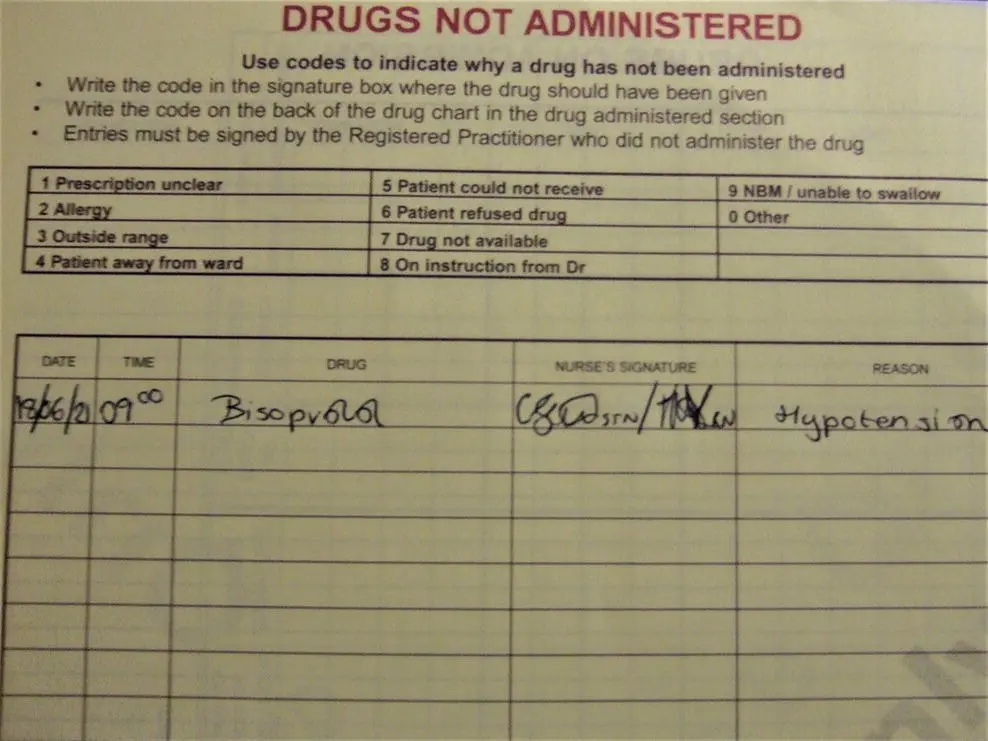

Figure 4.1 Mixing opinion and fact.

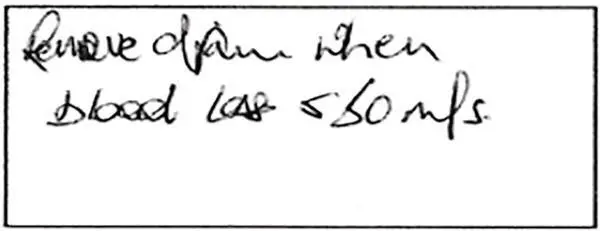

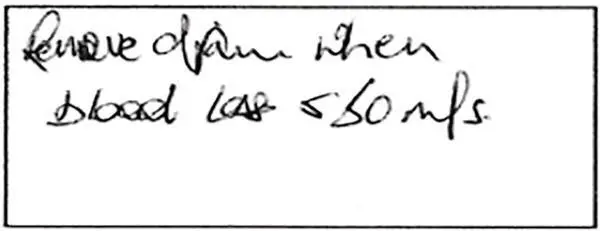

Figure 4.2 Illegible writing.

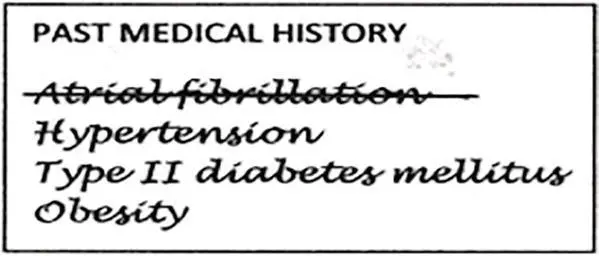

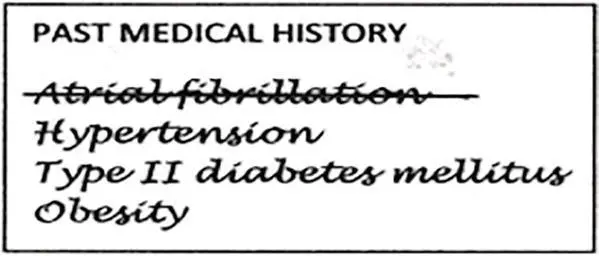

Figure 4.3 Removing an error.

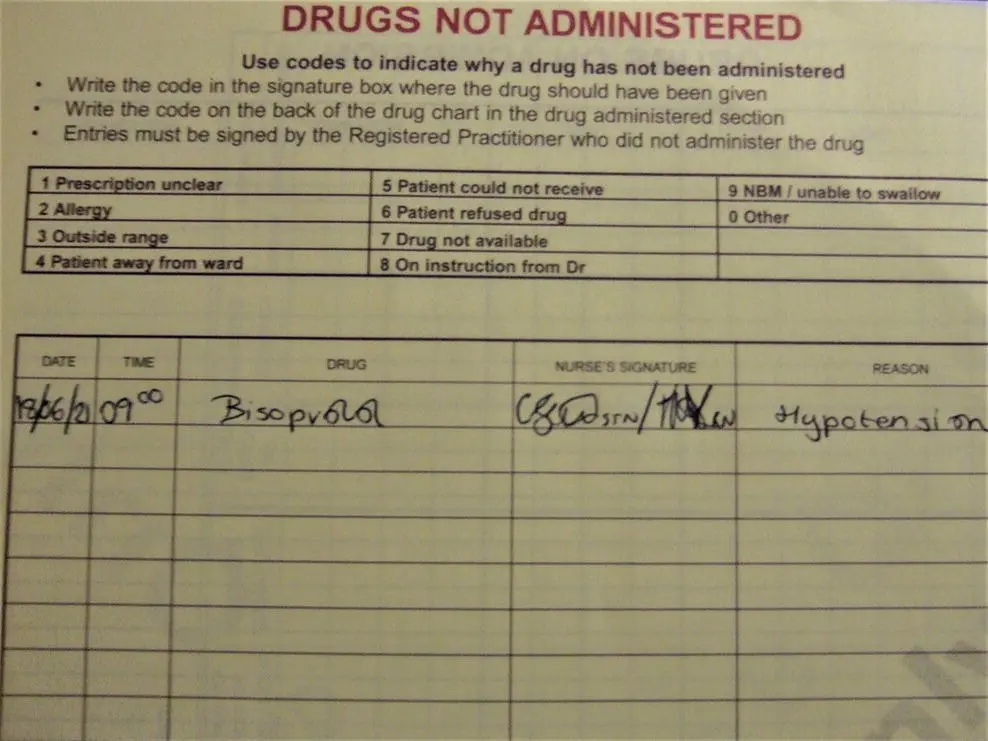

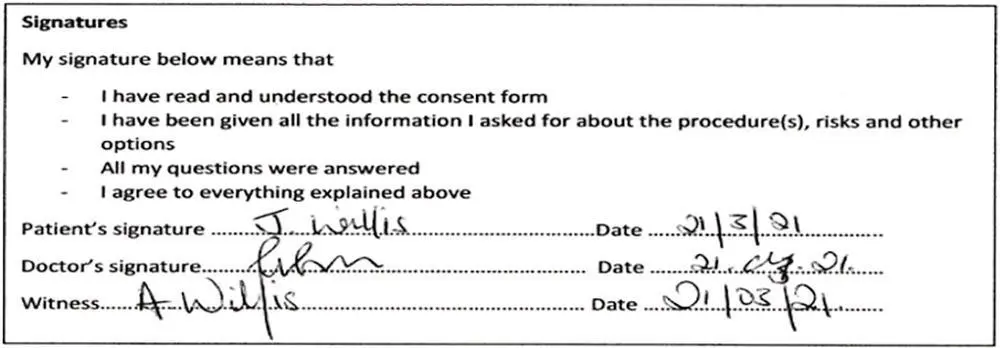

Figure 4.4 Designation and signature.

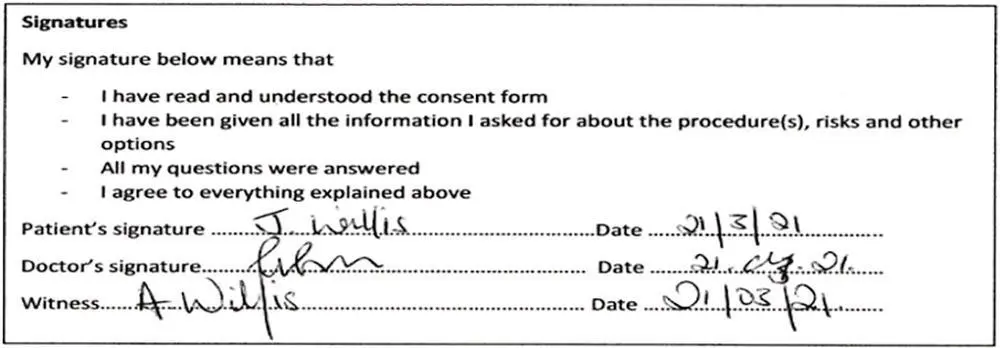

Figure 4.5 Counter‐signature.

Part 10 of the Nursing & Midwifery Council Code (NMC 2018) requires clear and accurate records to be kept.

Record keeping is a key part of our communication within the interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary team (RCN 2017).

Record keeping allows for communication of assessment, care planning, interventions, treatments, and evaluation.

Poor record keeping has been linked to poor care and raised patient safety concerns (Francis 2013).

While record keeping is key to providing continuity of care it should also be noted that any document can become a legal document once requested by the court (Dimond 2015).

Critically unwell and/or hypovolaemic patients.

Those who are agitated, confused or confrontational.

Those in status epilepticus or having regular seizures.

Needle phobia.

Time pressures – these pressures can result in documentation being delayed and thus it will not be as accurate as when recorded directly after the fact.

Time pressures – these pressures can also cause handwriting to be illegible and result in typographic errors when using electronic records.

Insufficient training on the documentation used can result in mistakes and/or omissions.

Healthcare workers must remain up to date with training on record keeping, data collection, and storage and be aware of legal requirements about these.

The correct document to record the specific actions taken.

Access codes may also be required.

Procedure – Standard Documentation

Ensure that documentation is performed as soon after the fact as possible (RCN 2017).

Avoid unnecessary abbreviations or abbreviations that could have multiple meanings, e.g. MS could refer to multiple sclerosis or mitral stenosis.

Avoid unnecessary and/or inappropriate comments, such as mixing opinion and fact (Dimond 2015) ( Figure 4.1).

Avoid slang, jargon, derogatory, and any other comments that could be classed as unprofessional.

Provide accurate and concise details of the intervention.

Provide details on any future care required, i.e. next dressing change, evaluation of current care.

Read through the work and ascertain if it would be understandable to the person who was provided with care (RCN 2017).

Ensure that it is legible ( Figure 4.2).

If any errors are noted on written documentation, cross through the words with a single line ( Figure 4.3).

Provide date, time, and location of intervention.

Provide designation and signature ( Figure 4.4).

Ensure a counter‐signature is provided where required ( Figure 4.5).

Procedure – Writing a Statement

You can be asked to write a statement as a witness to an incident, if you are under investigation, if you are raising a concern, or if you have a grievance. Professional bodies provide guidance and support on how to write individual statements but below are some key points:

Provide your name, position, date, and subject heading – this includes any reference numbers.

Highlight what this is connected to and the date and time of the incident. The introduction should also state your role in the incident.

Provide a clear and full description of what occurred and when. Providing a clear account of an event can be challenging if a significant amount of time has elapsed. It is recommended that if you are involved in an incident that concerns you, you raise the concern and write the statement at that time.

Highlight who was involved – this may include other colleagues, patients, family members, friends, significant others, and other members of the general public.

Читать дальше