Supporting privacy and dignity is also a human right with three specific articles of the UK Humans Rights Act (1998) focusing on these ( Table. 8.2).

Privacy and dignity also refer to maintaining the privacy and dignity of patients, employers, and other employees actions outside of the work environment – this is specifically important when engaging with social media.

Emergency situations – when saving life is a priority, both privacy and dignity can be forgotten. Closing the curtain or door can be helpful, but as multiple members of the team may be entering and leaving the room, closing the curtain or door of surrounding patients can reduce exposure.

The unconscious patient is unable to express preferences – this information may be provided by other sources (e.g. family members, patient’s notes) but advocating for the patient is also required in these circumstances.

Lack of capacity – sharing of information in these situations can be challenging. Avoid assuming that information can be provided and look for a lasting power of attorney form.

Time pressures – these pressures can result in a lack of privacy when providing sensitive care.

Time pressures – these pressures can also cause healthcare workers to disregard patient dignity by not considering patients’ preferences. which could be based on cultural, religious or other practices.

Maintaining privacy requires healthcare professionals to treat the patient as an individual for each individual interaction; not doing so can disregard legal and professional requirements.

A ‘do not disturb’ clip to use with curtains ( Figure 8.1).

A roller blind for door windows.

Appropriate documentation security.

Procedure – Key Considerations

Ensure the procedure is fully explained and informed consent is obtained.

Check that there will be no interruptions for the duration of the procedure; use ‘do not disturb’ signs.

Advise members of your team, and the nurse in charge where you will be, as appropriate.

Ask the patient their preference for the procedure, e.g. “Would you prefer for the curtain to be open or closed while I measure your vital signs?”

Explain what you are doing throughout.

Ensure the patient has adequate levels of privacy for their requirements before you leave the area.

Follow the record‐keeping guidance for clear, accurate, professional documentation.

Follow data protection requirements for storage of all patient data (Data Protection Act 2018).

Note – supporting the patient to be independent when providing person care is preferred but not always possible. Encouraging the patient to provide care for their genitalia can support privacy and maintain dignity.

Unprofessional and unlawful conduct across social media has resulted in professional bodies providing guidance on managing your social media profile (GMC 2013; NMC 2018b). The NMC has recommended that professionals follow the six Ps before posting on any platform (see Table 8.3). It has also highlighted that fitness to practise will be questioned in the following instances:

There is sharing of confidential information inappropriately, i.e. without patient consent or providing employer – and thus healthcare provider – details.

There is posting of unprofessional comments about people they provide care for, other team members, and/or employer.

There is posting that could be considered as bullying or exploitation of patients, other team members, and/or the employing organisation.

There is posting of pictures or videos without the party's consent (NMC 2018b).

Failing to comply with professional requirements can result in a fitness‐to‐practice review and lead to removal from the professional register.

Failure to follow the law will bring legal recriminations, which could include tribunal cases brought by an employer, breach of professional negligence under case law, or a breach of a specific Act of Parliament. These incur penalties such as fines, community sentencing, and imprisonment.

1 Data Protection Act (2018) c12. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted(accessed 22 April 2020).

2 General Medical Council (2013). Doctor's Use of Social Media. London: General Medical Council.

3 Human Rights Act (1998) c.42. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/42/contents(accessed 22 April 2020).

4 Nursing & Midwifery Council (2018a). Professional Standards and Practice of Behaviour for Nurse, Midwives and Nursing Associates. London: Nursing & Midwifery Council.

5 Nursing & Midwifery Council (2018b). Guidance on Using Social Media Responsibly. London: Nursing & Midwifery Council.

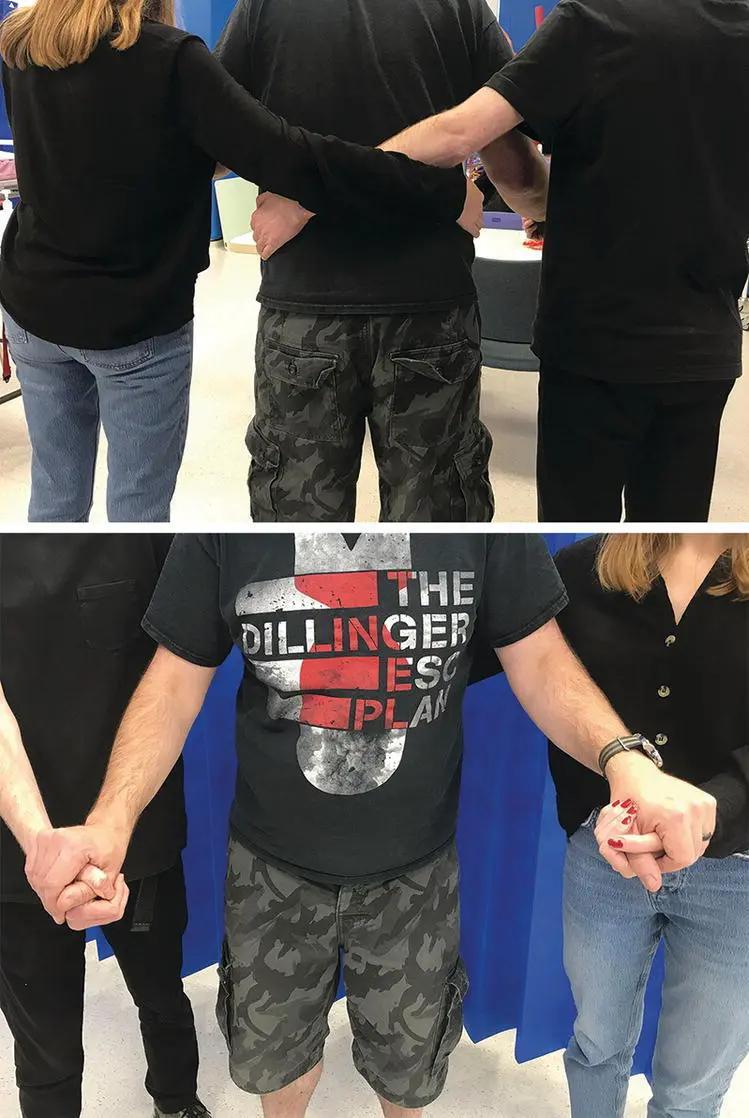

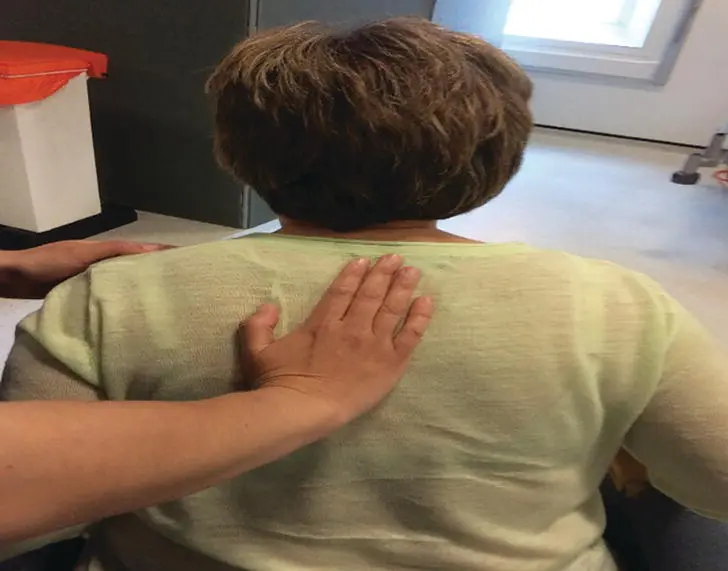

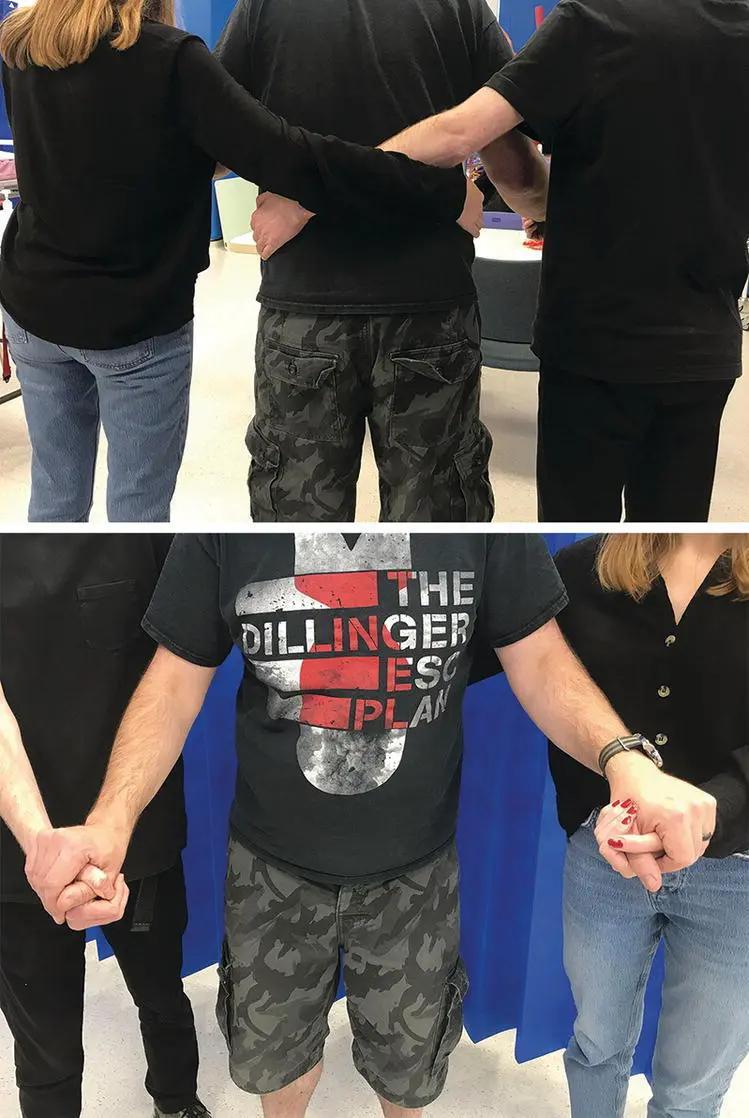

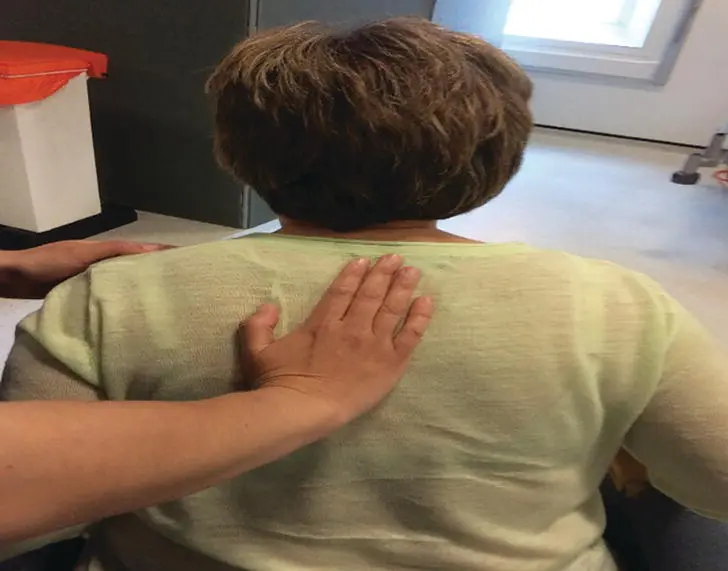

Figure 9.1 Sit to stand.

Figure 9.2 Walking with assistance of one.

Figure 9.3 Walking with assistance of two.

Table 9.1 Using TILEO for safety in manual handling.

Source : Based on Smith 2011.

| Task |

Does the task include twisting, stooping, bending, pushing, pulling, or sudden movement? |

| Individual |

Consider the patient and the handler with respect to health, e.g. disability, pregnancy |

| Load |

Consider weight, stability, ability to grip |

| Environment |

Consider space constraints, flooring – stable, same level, hot/cold conditions |

| Other factors |

Is the movement hindered by infusions, traction, drains? Have you the correct working equipment? |

Figure 9.4 Walking with a frame.

Figure 9.5 Standing to sitting.

Moving and handling (MH) refers to the assistance given to a load 1 to enable it to move.

These include lifting, putting down, pulling, pushing, carrying, supporting a load whilst static, throwing or moving by hand or bodily force.

MH is governed by the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and welfare legislation (National Back Exchange 2010), which include regulations for employers and employees to understand, and subsequently follow, to ensure their own and others’ safety.

MH procedures are often utilised in healthcare settings when assisting a patient with their mobility but can be applied to any environment where the MH of a load is required, e.g. supermarkets, warehouses, and mechanics’ garages.

Читать дальше