Equipment and Emergency Supplies

Some of the most common emergency drugs and equipment that may be needed in an outpatient anesthesia setting are listed in Table 1.3. Emergency drugs are available from the manufacturer in appropriate dilutions that are prepackaged into syringes designed for single‐patient use. Though there is an increased cost when purchasing emergency drugs in this form, it allows a practitioner to select and administer an emergency drug as needed without delay and potentially minimizing calculation errors.

Table 1.3. Emergency drugs and equipment

| Emergency equipment: |

|

| Defibrillator |

|

| Suction (portable) |

|

| Oxygen tank with backup |

|

| Face mask (non‐rebreathing with bag valve mask) |

|

| Laryngoscope with light source, blades, extra batteries |

|

| Endotracheal tubes, cuffed/uncuffed |

|

| Laryngeal mask airway |

|

| Oral airways |

|

| Nasal airways |

|

| MacGill forceps |

|

| Tracheostomy/cricothyroidotomy set |

|

| Emergency drugs: |

|

| Epinephrine |

Atropine |

| Vasopressin |

Succinylcholine |

| Nitroglycerin |

Glycopyrrolate |

| Adenosine |

Lidocaine |

| Labetalol |

Metoprolol |

| Esmolol |

Diphenhydramine |

| Lorazepam or diazepam |

Hydrocortisone |

| Glucagon |

50% Dextrose |

| Naloxone |

Flumazenil |

| Albuterol MDI |

Aspirin |

When the surgical and anesthetic procedure is completed, the patient is discharged to a postoperative area where patient recovery from anesthesia is typically overseen by someone other than the surgeon. Due to the short‐acting nature of most anesthetic drugs currently in use, most patients begin to awaken by the end of the surgical procedure. Some patients may still be significantly sedated upon arriving to the recovery area, however, due to differences in patient response to anesthesia. Vital signs should continue to be monitored postoperatively. A trained staff member should be physically present in the immediate recovery area at all times and should observe the patient's condition, including skin color, respiratory rate and effort (chest rise), response to verbal or physical stimulation, and any signs of agitation or inability to be roused. Once patients are reasonably awake, they may be joined by a family member or friend, if space permits in the recovery area.

INCIDENCE OF COMPLICATIONS IN AMBULATORY ANESTHESIA

Though little historical data are available, it appears that ambulatory anesthesia has increased in safety over the past several decades. A recent large study reported an incidence of outpatient anesthetic complications of 1.45%, compared to a 2.11% complication rate for inpatient anesthesia [15]. Improvements in equipment design for the provision of anesthesia and patient monitoring as well as improvements in engineering controls, safety practices, and practitioner training have contributed to the overall low rate of anesthetic complications. Some of the more common complications of anesthesia, such as nausea and vomiting, have relatively low morbidity although the institutional costs may be high. Other complications such as respiratory or cardiac arrest are so morbid that significant effort has been made to adequately prevent and manage them despite their very low incidence. A proportion of complications are due to underlying patient factors such as patient age and medical comorbidities over which the practitioner has little control, but evidence has also shown that many complications are the result of operator error, equipment malfunction, or system failure. Preventable complications offer an opportunity for the individual clinician and the specialty as a whole to make improvements that increase patient safety and anesthetic success.

NEUROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS

Syncope

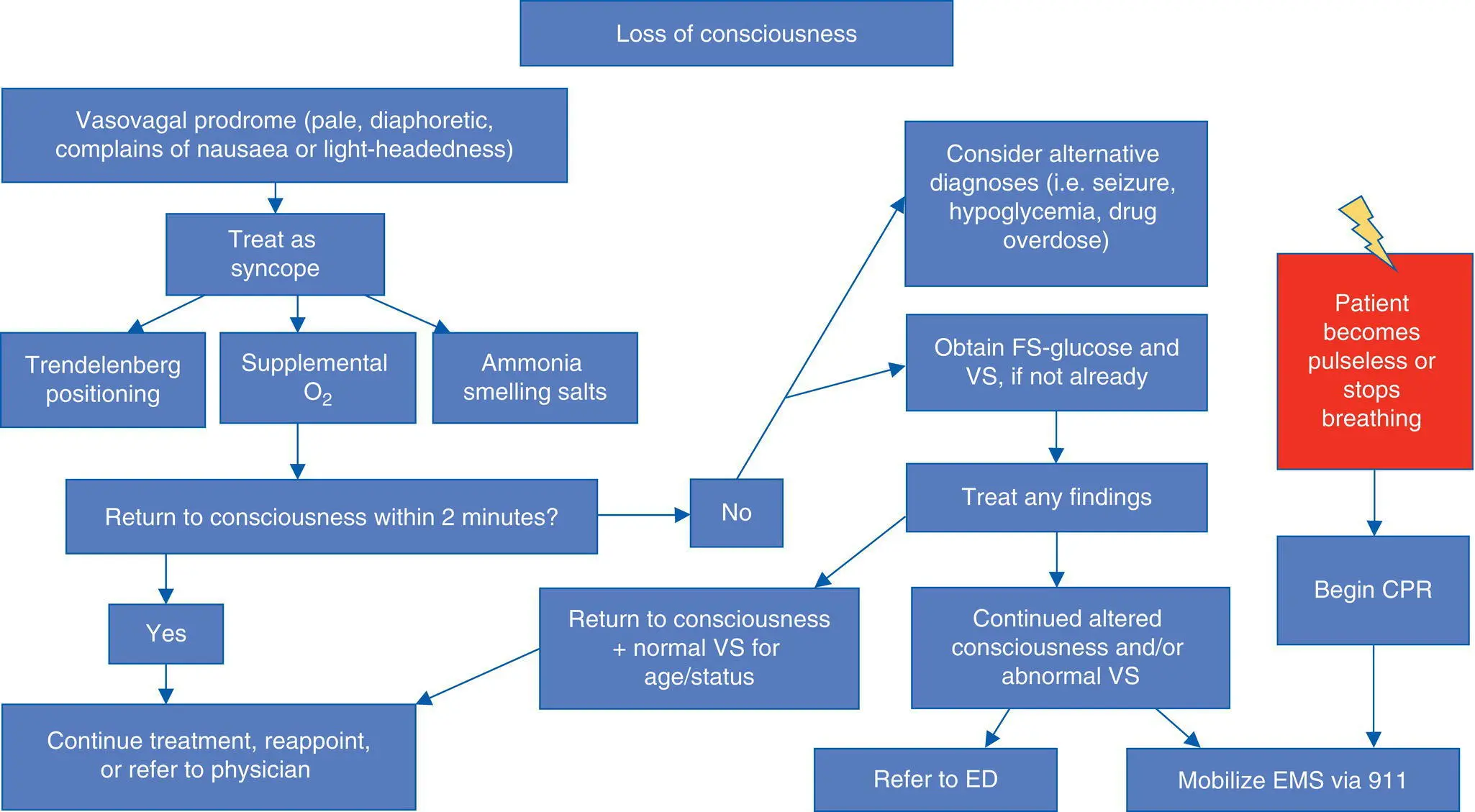

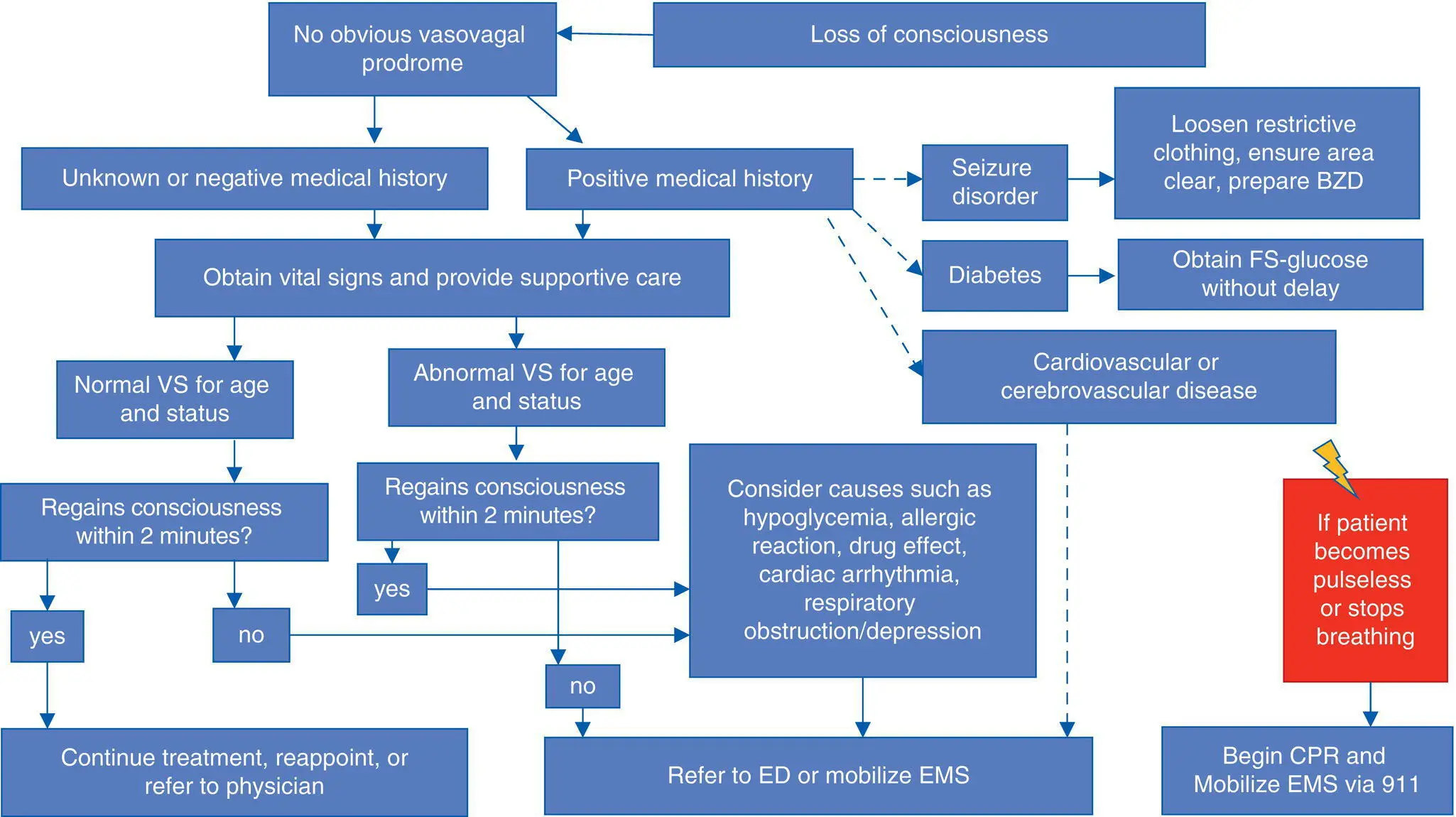

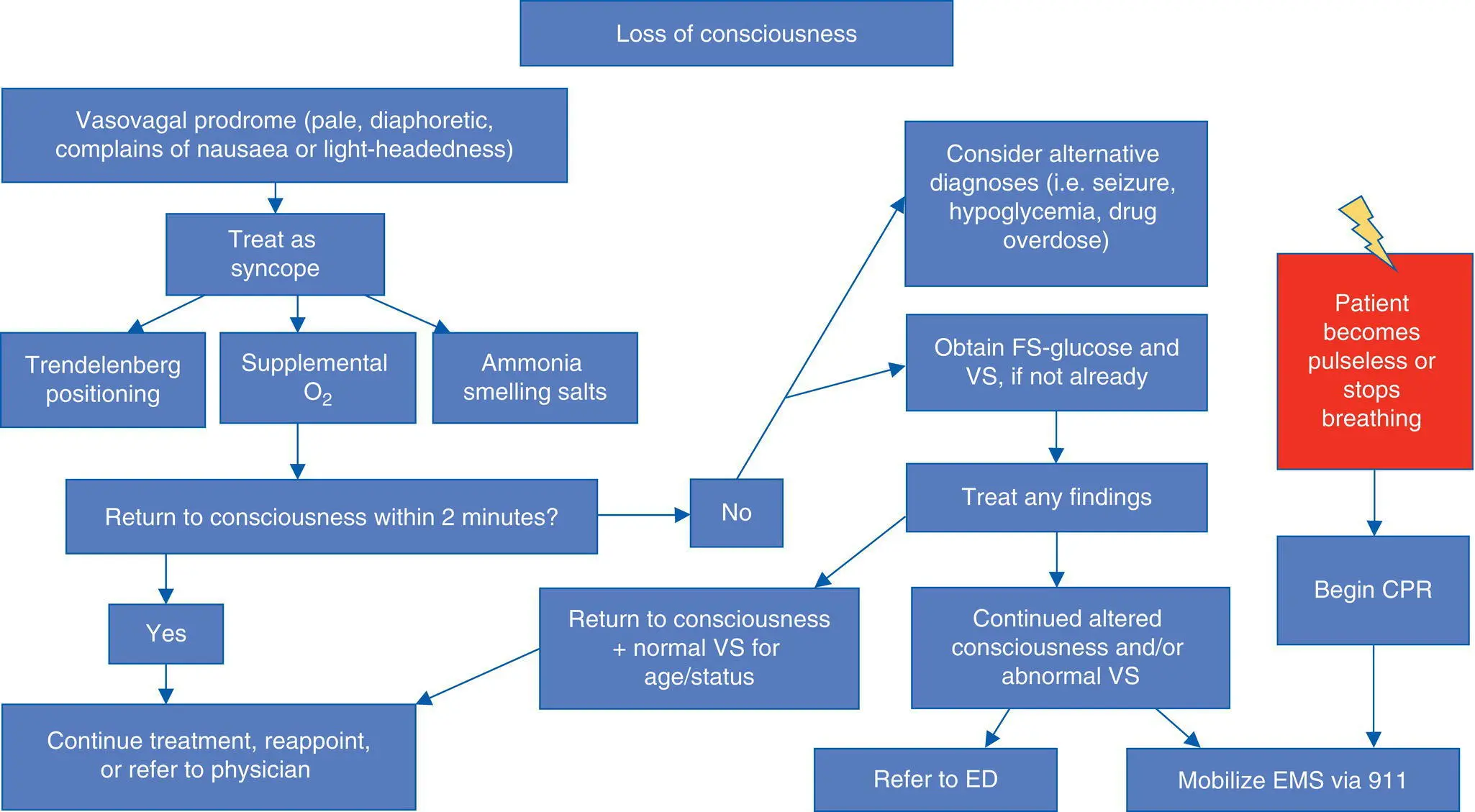

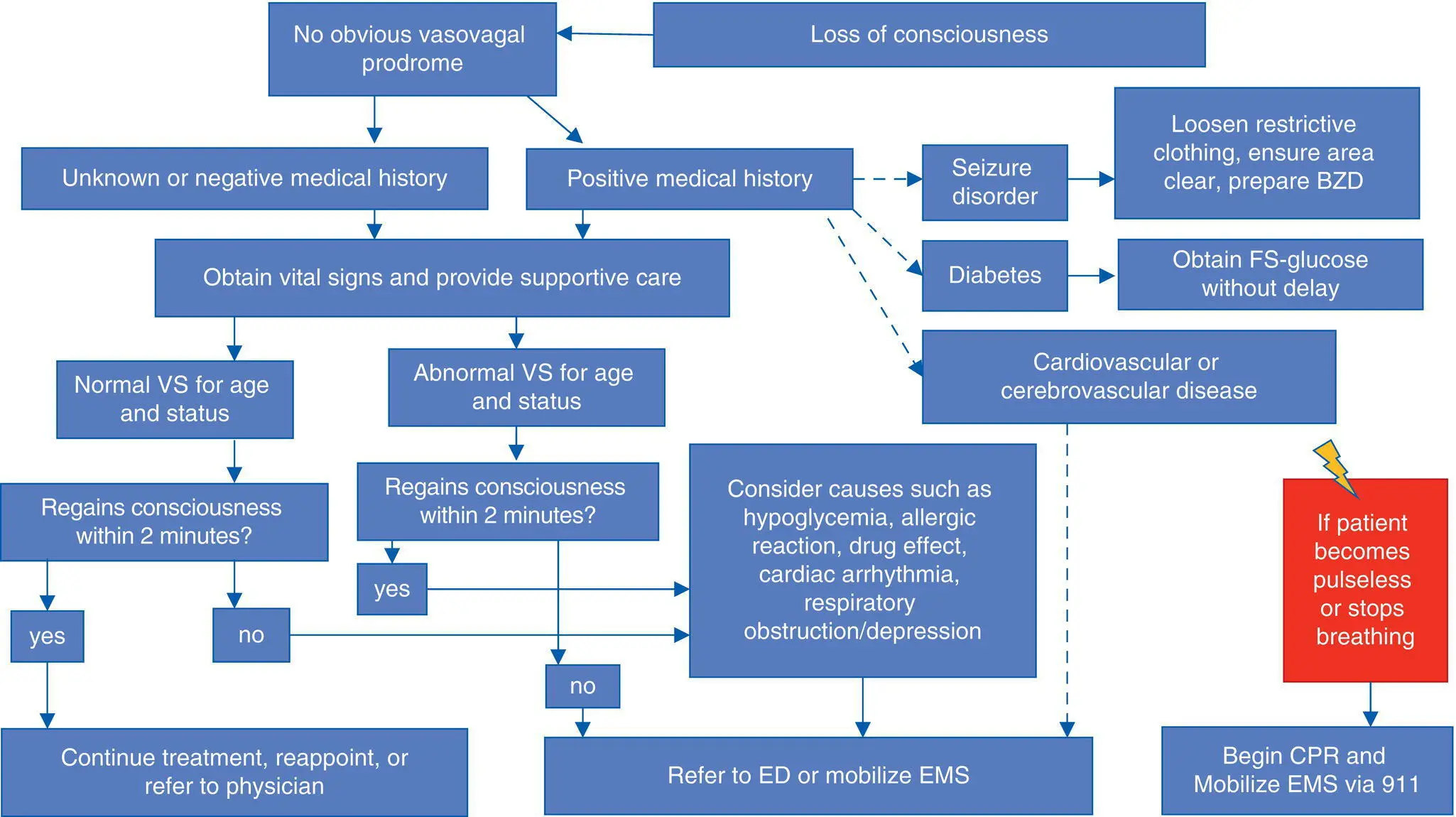

Syncope, one of the most common anesthetic complications, typically occurs in the preoperative setting, but may be observed occasionally postoperatively as well ( Algorithms 1.1, 1.2). Syncope is defined as transient loss of consciousness with spontaneous return to consciousness. In a study by D'Eramo, syncope was the most frequently observed complication, occurring in 1 out of 240 parenteral sedation cases and 1 out of 521 general anesthetic cases [1]. It is usually related to patient's anxiety in the preoperative setting and is most frequently observed upon venipuncture for placement of an IV line [16]. Syncope responds well to placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position, as this places the patient's head lower than the thoracic cavity and speeds blood return to the brain. Supplemental oxygen is beneficial and should always be given; it is also useful in cases of near‐syncope. Ammonia smelling salts may also be helpful and are usually applied in situations where Trendelenburg positioning and supplemental oxygen do not result in a rapid return to consciousness.

In the postoperative period, patients may experience syncope due to vasovagal response or transient orthostatic hypotension when rising too quickly from a seated or supine position. This complication may be prevented by assisting all patients when they stand or begin walking, since syncope under these circumstances carries the additional risk of injury from falling. Management consists of patient positioning, supplemental oxygen, and ammonia salts if needed.

Any period of unexpected patient unconsciousness that lasts for several minutes is not considered true syncope. If a loss of consciousness episode lasts more than a few minutes, other causes should be investigated without delay, including the possibility of hypoglycemia, hypotension, dehydration, partial seizure, oversedation, or cerebrovascular accident.

Algorithm 1.1: Loss of Consciousness with Vasovagal Prodrome

Algorithm 1.2: Loss of Consciousness without Vasovagal Prodrome

Oversedation is a relatively common event observed during ambulatory anesthesia that can rapidly develop in severity. It initially manifests as lack of adequate patient response to appropriate stimuli. For example, a patient who previously responded to loud verbal or forceful physical stimuli may suddenly fail to respond. In cases of profound oversedation, a patient may fail to respond to increasingly painful stimuli, and when the plane of general anesthesia is reached, the patient will have lost protective airway responses. If allowed to progress without intervention, oversedation can rapidly advance to airway obstruction, hypopnea, or apnea leading to hypoxemia. In severe cases, respiratory depression can lead to respiratory arrest and depression of cardiac output will be observed.

Oversedation in ambulatory anesthesia takes two forms: unintended deep sedation or general anesthesia during the procedure, or prolonged or delayed awakening in the postoperative period. Intraoperatively, oversedation is produced by too high a dose of an anesthetic drug or a dose of anesthetic that is administered too quickly. Patient factors often figure prominently in cases of oversedation, as patients who are very sensitive to the effects of an anesthetic or who have greatly decreased elimination kinetics will have a narrowed therapeutic range compared to an “average” patient. It can be quite difficult to titrate anesthetic drugs in such a patient, with the result that oversedation is more likely to occur.

Читать дальше