Polar Organometallic Reagents

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Polar Organometallic Reagents» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Polar Organometallic Reagents

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Polar Organometallic Reagents: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Polar Organometallic Reagents»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Polar Organometallic Reagents

Polar Organometallic Reagents

Polar Organometallic Reagents — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Polar Organometallic Reagents», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

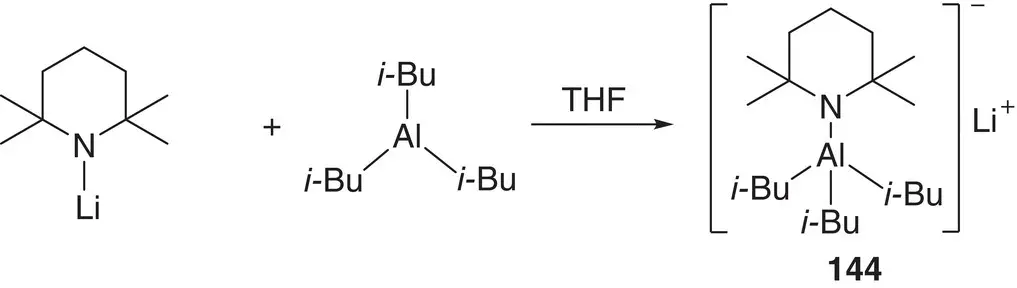

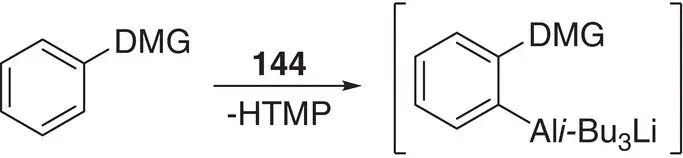

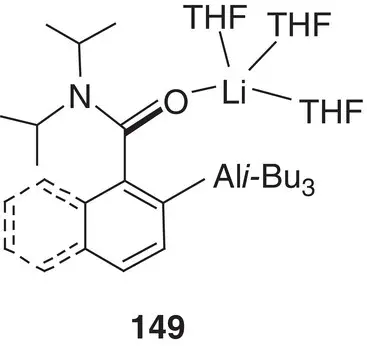

In the same way as the principles of structural chemistry have been applied to alkali metal zincates, allowing the interrogation of basic reagents and reaction intermediates and the development of an improved understanding of reaction processes, so have they helped elucidate the activity of aluminates. Four‐membered metallacycles akin to those reported for dialkylamidozincate bases are seen for trialkylamidoaluminates such as i ‐Bu 3Al(TMP)M(L) (M = Li, L = THF 147; M = Na, L = TMEDA 148; the crystal structure of the first is exemplified in Chapter 2, Figure 2.21) [205, 206], though a dialkyldiamidoaluminate has also been suggested, based on two metal‐bridging amides (see below) [207]. As with zincate chemistry, the alkali metal proved straightforwardly variable; though while Li and Na were relatively simple to work with [205, 206], K proved more problematic and required PMDETA as a stabilizing additive to prevent the TMP ligand from degrading [208]. As for zincates, reactivity was more complex and subtle than might at first have been expected. The polybasicity reported for zincates was not observed for 144, a fact rationalized theoretically in terms of the contrast between closed‐shell Al in a tetraorganoaluminate and 16 e −Zn in a triorganozincate [209]. Moreover, as spectroscopic studies have subsequently made clear, the heterobimetallic nature of isolated alkali metal aluminates belies the possibility of different reactive pathways. Instead of synergic reactivity and direct alumination of organic reagents, cooperative cleave‐and‐capture chemistry could occur whereby the deprotonative alkali metalation of an organic can instead precede the formation of an Al–C bond, so ‘capturing’ the reactive anion [93]. In either case, amide abstraction of a proton from the ortho position of the aromatic reagent is favoured. The intermediates expected for such processes were structurally modelled by sequentially treating ArC(O)N i ‐Pr 2with t ‐BuLi and i‐ Bu 3Al in THF to obtain diffraction quality crystals of 149( Figure 1.19). Their stability in solution was also studied, with partial desolvation observed in hydrocarbon media. In spite of this, exposure to excess HTMP failed (in accordance with theory) to affect the reaction (i.e. quenching of the amine) [209]. The complete passivity of either ortho ‐aluminate towards HTMP has been further evidenced by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic analysis using (non‐polar) benzene or (Lewis basic) THF media and introducing excess amine by injection. In either solvent, chemical shifts attributable to ortho ‐aluminate were unchanged upon addition of amine, even after heating to reflux.

Scheme 1.31 Synthesis of i ‐Bu 3Al(TMP)Li 144.

Scheme 1.32 Ortho ‐alumination of a functionalized aromatic ring.

Figure 1.19 Model aluminate 149, obtained by sequentially treating ArC(O)N i ‐Pr 2with t ‐BuLi and i ‐Bu 3Al in THF.

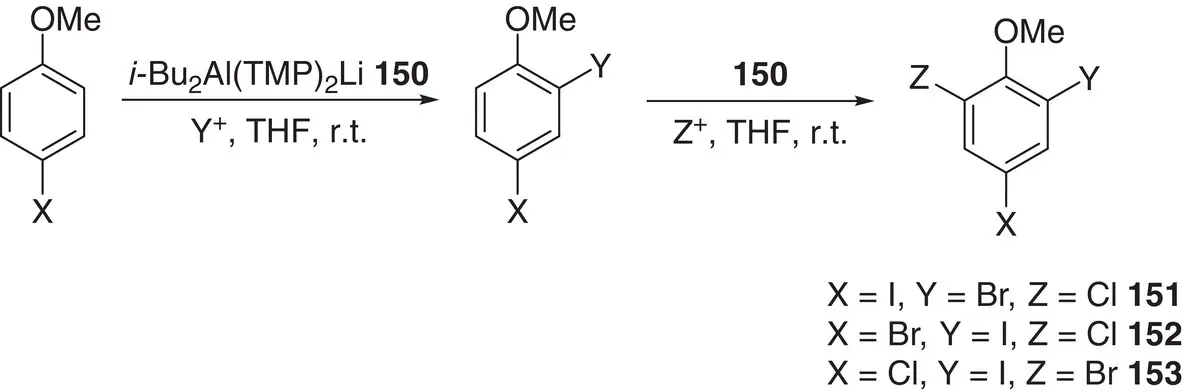

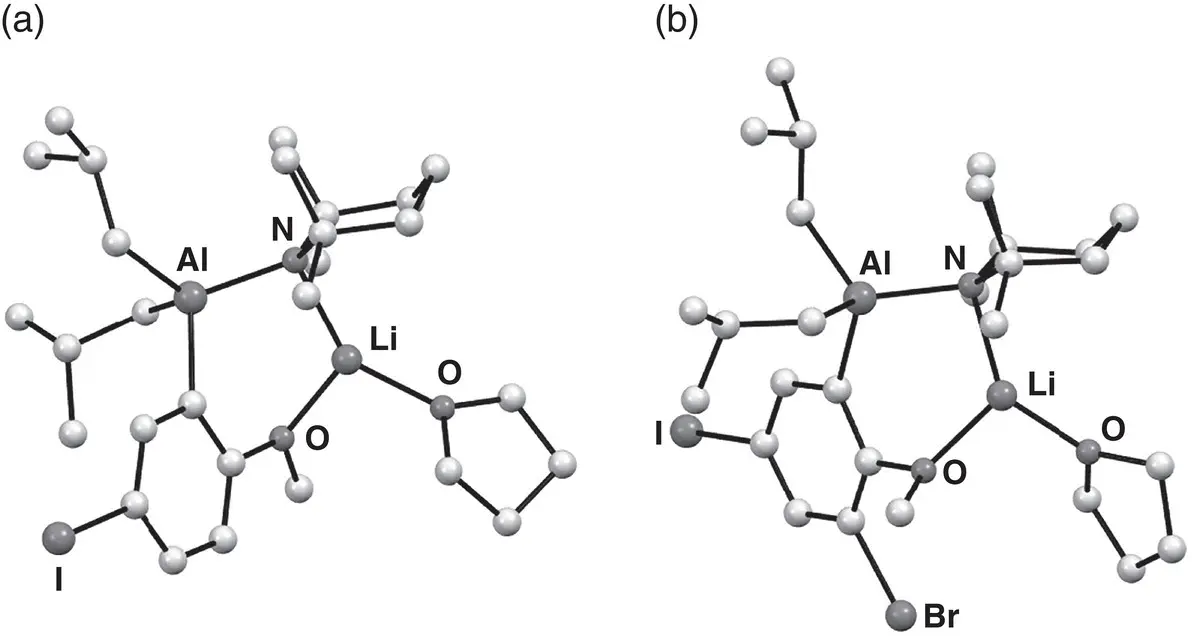

The synthetic utilization of kinetic basicity was a fundamental driver for developing the aluminate systems described here. This mode of action has been nicely demonstrated, albeit in a nonaromatic aside; regioselectively functionalizing unsymmetrical ketones. Methyl isopropyl ketone reacted with a mixture of i ‐Bu 3Al and LTMP at 0 °C in THF to selectively give the kinetic enolate with near complete selectivity. Subsequent electrophilic trapping with benzaldehyde then proceeded smoothly to give only the corresponding regioisomer. A range of other unsymmetrical acyclic and cyclic ketones then demonstrated similar kinetic regioselectivity in their functionalization, even under harsh conditions; heating to reflux in THF for 18 h [209]. In an example of interesting functional group tolerance by aluminates, use of the dialkyldiamidoaluminate [207] i‐ Bu 2Al(TMP) 2Li 150has enabled the highly efficient, facile conversion of 4‐halo‐anisoles to synthetically important triheterohalogenated anisoles ( 151– 153) through the sequential reaction of a 4‐halo reagent with sulfuryl chloride, N ‐bromosuccinimide and/or iodine ( Scheme 1.33) [210]. Of course, the impressive compatibility of the base with halogenated reagents underpins this reactivity. This contrasts strongly with that of many traditional organometallics and it extended to the ability to isolate and fully elucidate ortho ‐aluminated intermediates in both the first ( 154) and second ( 155) halogenation processes ( Figure 1.20).

Scheme 1.33 i‐ Bu 2Al(TMP) 2Li 150has enabled the conversion of 4‐halo‐anisoles to triheterohalogenated anisoles 151– 153.

Figure 1.20 Molecular structures of aluminated precursors 154and 155to (a) di‐, and (b) triheterohalogenated anisole derivatives, respectively.

Source : Adapted from Conway et al. [210].

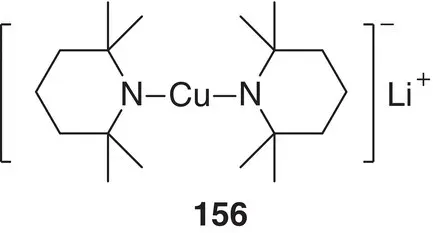

Figure 1.21 Representation of the Gilman amidocuprate (TMP) 2CuLi.

1.4.5 Cuprates

Whilst lithium organocuprates ( Section 1.3.3) have established dominance amongst the transition metal organometallics used in synthesis, several different flavours of reagents have evolved to suit various applications. These include heteroleptic cuprates, which normally combine organyl and heteroatom‐based ligands as a means of increasing organyl transfer efficiency; organoamidocuprates are one such well‐studied member of the heterocuprate family. They have become known by virtue of their unique features and reactivities. They have many potential applications in organic transformations, especially in stereoselective synthesis because the amido ligand can act not only as a dummy (nontransferable) group but also as a chiral auxiliary [211]. The non‐transferability of amido (heteroatom) ligands on cuprates in carbon–carbon bond forming reactions has also been theoretically clarified by DFT calculations [212]. A new use for amidocuprates was investigated, wherein the amido ligand transfers (reacts) first as a base for chemoselective directed ortho ‐cupration and then as a switch in successive C–C, C–O, and C–N bond formation processes [213, 214]. To develop new applications of amidocuprates, the deprotonative metalation of functionalized benzenes was investigated [215]. Initial studies used benzonitrile as a model aromatic compound with an electron‐withdrawing group to identify favourable reaction conditions. These indicated that a TMP group as the amido moiety and THF as solvent were suitable starting points for the optimization of directed metalation reaction conditions ( Figure 1.21). Attempts to use the Gilman amidocuprate (TMP) 2CuLi 156prepared from CuI proved unsuccessful in terms of reactivity and directed metalation selectivity. On the other hand, the use of CuCN was presumed to result in the incorporation of cyanide and the formation of so‐called Lipshutz amidocuprates. Two examples, putatively (TMP) 2Cu(CN)Li 2 157and MeCu(TMP)(CN)Li 2 158, have been proposed to exemplify this, with reaction mixtures incorporating the appropriate amounts of the necessary components (CuCN, LTMP and, for 158, MeLi) enabling metalation without any catalyst, in good yields at 0 °C (summarized in Scheme 1.34and explored in depth in Chapter 8). It was found that although the latter case employed a CuMe‐containing reagent, at least one TMP ligand, one of the bulkiest available amido ligands, was crucial for good yield and chemoselectivity.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Polar Organometallic Reagents»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Polar Organometallic Reagents» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Polar Organometallic Reagents» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.