James Carl Nelson

THE POLAR BEAR EXPEDITION

THE HEROES OF AMERICA’S FORGOTTEN INVASION OF RUSSIA

1919–1919

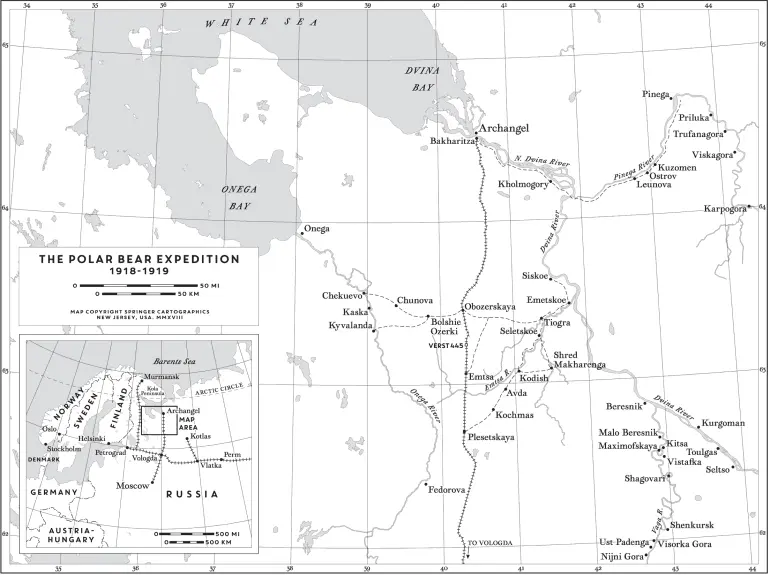

Nijni Gora, Russia

January 19, 1919

They’ve been expecting it for weeks—hell, months. And so the men of Company A of the 339th Infantry Regiment—the Polar Bears, they would come to call themselves—have stood night and day in forty-below-zero temperatures. They stamp their feet and try not to touch bare skin on the frozen barrels of their weapons lest their flesh be ripped off; they peer through the deep, ebony night from their dark, log-lined dugouts into the frigid tundra toward the south and east across the ice-choked river and watch for it, wait for it, and wonder how many will come and how they will perform when they do—and they wonder, too, if and how they will ever get out of this place, this frozen Hades, this last place on earth at the top of the world.

And then early on this morning they do come, a horde of them, dim forms in the distance spread out across the Vaga River, some on skis and others on snowshoes and all of them armed, like ghost warriors traversing the River Styx—hundreds of them to their mere handful of forty-six.

Bolos, the men call them.

Bolsheviks .

Now a shell, flung from upriver, arcing and piercing the barely gray of dawn, flies over the village. Lt. Harry Mead awakens with a start, quickly dons his fur hat and overcoat and boots, and races to the far outpost, where this scant group of half-frozen men stands guard against not only the enemy but the tide of history.

The sergeant hands him his field glass and he squints through the misty, blowing snow, the only sounds the sharp snapping of frozen tree branches and the dull booming of the river ice cracking. He sees them now, coming on several hundred yards in the distance, and he quickly understands that the company is probably doomed.

Now a grayish form enters his view, much closer, and he peels the glass from his eye. Steam comes from his mouth as the thin outpost is now about to be overrun by a nearer group of the enemy, who have snuck closer and rise like dervishes from their concealment in the deep snow.

Lt. Harry Mead, late of Valparaiso, Indiana, and Detroit, Michigan, stranded more than two hundred miles from his regiment’s base at Archangel, Russia, doesn’t have to speak as the mass of Bolos descends on his small detachment. His men are already furiously firing their machine guns and rifles at this grisly apparition, all while more artillery shells spew over and land amid them. But Mead yells the words anyway, as if by rote, as if it’s not too late, as if any one of them has a chance.

“Fire!” Mead orders his men. “For God’s sakes, fire!”

Chapter One

The March to Intervention

The preliminaries began on March 9, 1918, with millions of high-explosive and gas shells raining across the front between the northern French cities of Ypres and St. Quentin; the smothering of the British-held territory continued through that week and beyond, and was topped off with a continuous salvo from 6,700 pieces of German artillery, which began at 4:40 A.M. on March 21.

Five hours later, heavy mortars began raining death and destruction on the British Fifth Army, and five minutes later the advance of three German armies, sixty-nine divisions in all, poured from their trenches and headed east, with the aim of splitting the junction of British and French forces on the southern end of the Somme front and sending the Brits in a panic for the protection of the Channel ports.

There was an urgency to the assault, and for good reason. With the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, Russia had officially taken itself out of the war and relieved the pressure on Germany’s Eastern Front. After years of fighting a two-front war, German forces were now consolidated. Meanwhile, the United States, which had declared war on Germany nearly a year before, had yet to send enough men across the Atlantic to tip the balance in the Allies’ favor on the Western Front. But the Yanks were coming. During that spring of 1918, therefore, Germany had a small and unique window in which to act while the numbers favored them, and so the handpicked assault troops went forward in great and deadly haste.

Above the attackers, 326 fighter aircraft soared into the morning, their opposition just 261 British planes. Following barrages, small teams of storm troopers appeared out of the deep fog and, ignoring the British strong points, cut swaths through the trenches with light machine guns, automatic weapons, and flamethrowers.

By the end of the first day of what would be a months-long offensive, the Germans had pushed more than four miles through the British and were still advancing. In their wake, they left the bodies of an untold number of defenders, thousands of wounded, and 21,000 prisoners. By March 23, three huge guns made by the arms manufacturer Krupp had been hauled forward and began sending shells into Paris, seventy-two miles away. Two hundred Parisians would be killed on that day alone.

Those unlucky Parisians would be but grains of sand in an ocean of war that had enveloped France since August 1914, when a gray tide of Germans had pushed across the border with Belgium and by early September had very nearly taken Paris. The flood was checked on the Marne River east of the French capital in early September, but the war—it would eventually become known as the Great War—had only begun. The Germans intended to stay, and by the end of 1914 a dizzying series of parallel zigzagging trenches—German, French, and, to the north, those of France’s British allies—scarred the French soil from Switzerland to the North Sea as all sides settled into a deadlock.

Over the ensuing months and years, incredibly costly attempts would be made on all sides to break that deadlock, only to fall victim to a new generation of powerful killing tools, chief among them the machine gun, long-range artillery, and gas. The men, meanwhile, lived like troglodytes in the trenches, sloshing about in knee-high water and dodging rats that fed on the dead, and poking their heads above ground only to watch for a coming enemy attack across the scarred ground pocked by shell holes and barbed wire and mud.

And the attacks did come, from all sides. At Loos in the fall of 1915, more than eighty percent of an attacking force of 10,000 Brits were killed or wounded, cut down in rows by machine guns as they advanced. In a single day—July 1, 1916—at the Somme more than 20,000 British soldiers were killed and another 25,000 wounded, this although more than 200,000 artillery rounds had been fired at the German lines prior to the attack. Between July 1916 and the following November, the British would take six miles of ground, losing almost 100,000 men in the effort; the Germans, meanwhile, lost more than 160,000 men over the same period and same ground.

The French fared no better. An April 1917 offensive at the Aisne River was launched with the hope of capturing six miles of territory, employing newfangled tanks in battle for the first time. But the advance quickly ground down, and by the time it was called off, 100,000 French had become casualties. By then, the French had lost so many men—almost 1.4 million French soldiers would die by the end of 1918, a number dwarfed only by the 1.8 million Germans killed in the war—that there were open revolts in the ranks. Fifty French soldiers— poilus —were subsequently tried, found guilty of mutiny, and shot by firing squads, while hundreds of others were imprisoned.

Читать дальше