Not wanting Cole’s pessimism to sway Wilson’s coming decision on intervention, Francis was careful to mail Cole’s passionate arguments to Washington instead of cabling them.

Cole’s well-thought-out thesis would not arrive in the U.S. until July 19; meanwhile, even while Wilson and his cabinet continued to argue that no resources should be spared on the Western Front and believed that that was where the war would be won, the Allied Supreme War Council on June 3, 1918, recommended the occupation of Murmansk and Archangel to counter any German threats, and decided that the British should be in command of any expedition.

British foreign secretary Alfred Balfour pressed Wilson to send a brigade—two regiments—“and a few guns” to Murmansk, and he discounted any fears that the soldiers would see any real action. He, like many in the Allied governments, regarded Trotsky and Lenin and their Bolshevik cronies as little more than thugs, and few could imagine that the Red government would last very long.

“It is not necessary that the troops should be completely trained,” Balfour said, “as we anticipate that military operations in this region will only be of irregular character.”

Slowly, Wilson’s opposition to intervention was eroding, and a plan of action, with the Czechs at the center, began to emerge. Secretary of State Robert Lansing argued that “furnishing protection and assistance to the Czecho-Slovaks, who are so loyal to our cause,” would differ from “sending an army into Siberia to restore order and save the Russians from themselves.”

On the evening of July 16, the sixty-one-year-old Wilson, admittedly “sweating blood” over the issue of intervention, sat down and poured out his agonized, sometimes contradictory assent to sending American troops into Russia.

In his aide-mémoire, he would vow that the “whole heart of the people of the United States is in the winning of the war” and they wished “to cooperate in every practicable way with the allied governments, and to cooperate ungrudgingly.”

He would go on to assert that the United States could not “consent to break or slacken the force of its present effort by diverting any part of its military force to other points or objectives.” An intervention in Russia, he continued, “would add to the present sad confusion in Russia rather than cure it, injure her rather than help her, and that it would be of no advantage in the prosecution of our main design, to win the war against Germany.”

But then, while opposing any intervention he vexingly allowed that he did support “military action” in Russia to aid the Czechs—and went on to write:

“Whether from Vladivostok or from Murmansk or Archangel, the only legitimate object for which American or allied troops can be employed… is to guard military stores which may be subsequently needed by Russian forces and to render such aid as may be acceptable to the Russians in the organization of their own self defense [ sic ]… For helping the Czecho-Slovaks there is immediate necessity and sufficient justification.”

Carefully worded, the aide-mémoire went to great lengths to deny that any American military presence, whether in the east or in the north, would constitute an organized “military intervention.” Such presences, instead, were simply “modest and experimental” missions.

American troops in the European north, who would operate as the American Expeditionary Force, North Russia, Wilson added, would simply guard materiel. The soldiers sent across the Pacific to Vladivostok, the American Expeditionary Force, Siberia, would similarly guard stores, and also help the Czechs who were moving west along the Trans-Siberian Railroad in an attempt to link with their brethren heading east.

As one author notes, the “rambling, misguided document” would result in American troops being sent into Russia without “a clear understanding of their purpose.” It also ignored the actual stated British and French aim of the intervention in northern Russia: a drive to connect with a Czech army that was supposedly coming west, and the subsequent reestablishment of the Eastern Front.

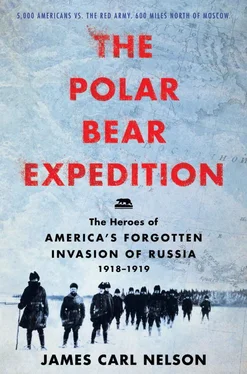

As Felix Cole had prophesized, that strategy would result in the swallowing up of the American force sent to northern Russia, and the loss of more than two hundred American lives, some of whose bodies remain under the taiga and hidden in the deep forests of northern Russia.

No one saw it coming, not one of them. Not Harry Costello or Joel Moore or Godfrey Anderson; not Harry Mead, nor Charlie Ryan, nor Robert Boyd, nor Thurman Kissick nor Clyde Clark nor Clifford Ballard nor Glen Weeks, nor Herbert Schroeder nor any of the men of the U.S. Army’s 339th Infantry Regiment as they labored at Michigan’s Camp Custer in the spring and summer of 1918 while their futures were being decided in Wilson’s White House and the stuffy environs of London’s 10 Downing Street and the Allied Supreme Council at Versailles, outside Paris.

Organized in August 1917, the 339th—one of four regiments that made up the Eighty-Fifth Division—consisted mostly of draftees from Michigan, and there were so many from the area around Detroit that the regiment called itself “Detroit’s Own.”

One man of the 339th would describe the mélange of troops as “factory workers, farmers, office help, school teachers. Some who could neither read nor write, from Kentucky or Tennessee. Some from Europe who had been in the U.S. for a month or years. A few who had been in some trouble, and had joined the Army to stay out of jail.” Among them, too, were Slavic-speaking immigrants, Russians, Poles, and others from eastern Europe; they could not know that as they trained at Camp Custer their language skills would one day come in very handy.

To a man, all believed and hoped that one day they would steam for Europe and fight on the Western Front; their more immediate realities entailed learning what they could of the ways of the military under the guidance of U.S. Army regulars.

One of these young draftees was Godfrey Anderson, the twenty-two-year-old son of Swedish immigrants Fred and Sophia. Enjoying school and reading, the boyish-looking Anderson grew up on the family’s Sparta, Michigan, farm but elected to attend the larger high school in Grand Rapids. He played football and baseball before graduating in 1913 and then returning home, where he remained for the next five years.

But world events, chiefly the world war then raging, would make their way to the Anderson stead in Kent County, as they did to the homes of some four million American men in 1917 and 1918. In March 1918, Godfrey registered for the draft; he would be ordered to report to Camp Custer on May 28, the day on which the U.S. First Division was storming the German-held village of Cantigny.

He was soon marching, drilling, being inoculated for a variety of diseases, and being lectured about the dangers of venereal disease; he and the other green recruits were soon also being put in their places by the camp’s non-commissioned officers—one of whom, “a red headed foul-mouthed sergeant,” Godfrey would recall—read them the riot act as they prepared to drill in full uniform and equipment one day.

“He began by delivering a violent diatribe, mostly consisting of threats, cursing, and obscenities, his voice at times rising almost to a shriek as he belabored us with vituperation and insult, referring to us repeatedly as bastards and sons of bitches,” a shocked Godfrey would recall.

“What seemed incomprehensible was that an officer—a lieutenant—stood right behind him, impassive and preoccupied, making no slightest effort to temper this vile ranting.”

That officer could have been Harry Costello, a tough, diminutive Irishman from what was called Dublin Hill in Meriden, Connecticut. Standing just five foot seven and weighing less than 140 pounds, and already sporting in his midtwenties the battered face of a punch-drunk prizefighter, Harry was the son of Irish immigrant Patrick, an iron molder, and Katherine, also an immigrant from the Emerald Isle.

Читать дальше