Polar Organometallic Reagents

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Polar Organometallic Reagents» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Polar Organometallic Reagents

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Polar Organometallic Reagents: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Polar Organometallic Reagents»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Polar Organometallic Reagents

Polar Organometallic Reagents

Polar Organometallic Reagents — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Polar Organometallic Reagents», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

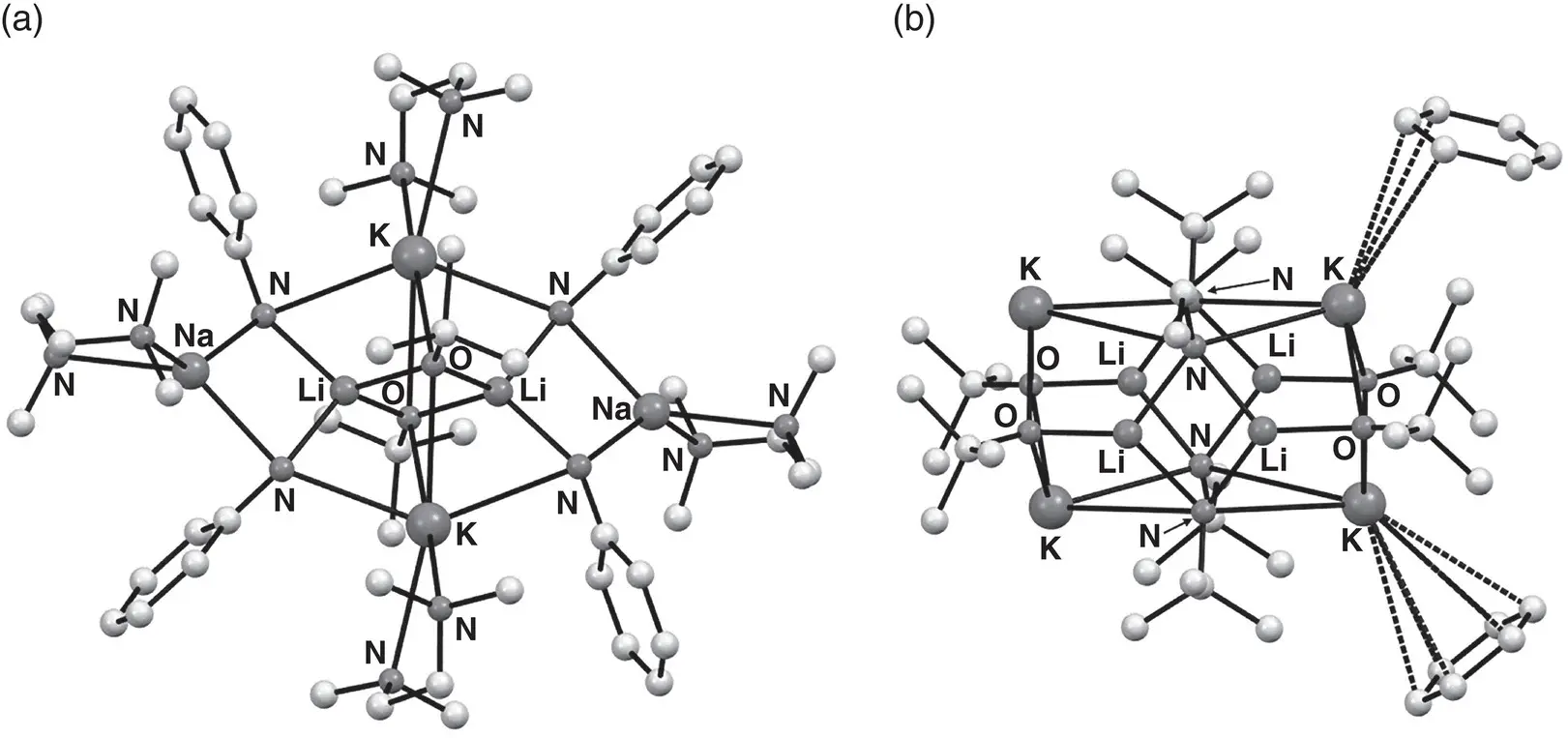

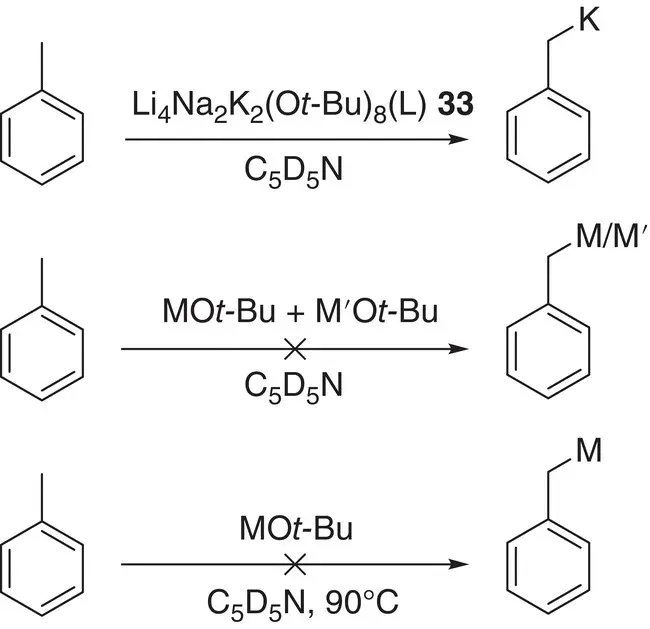

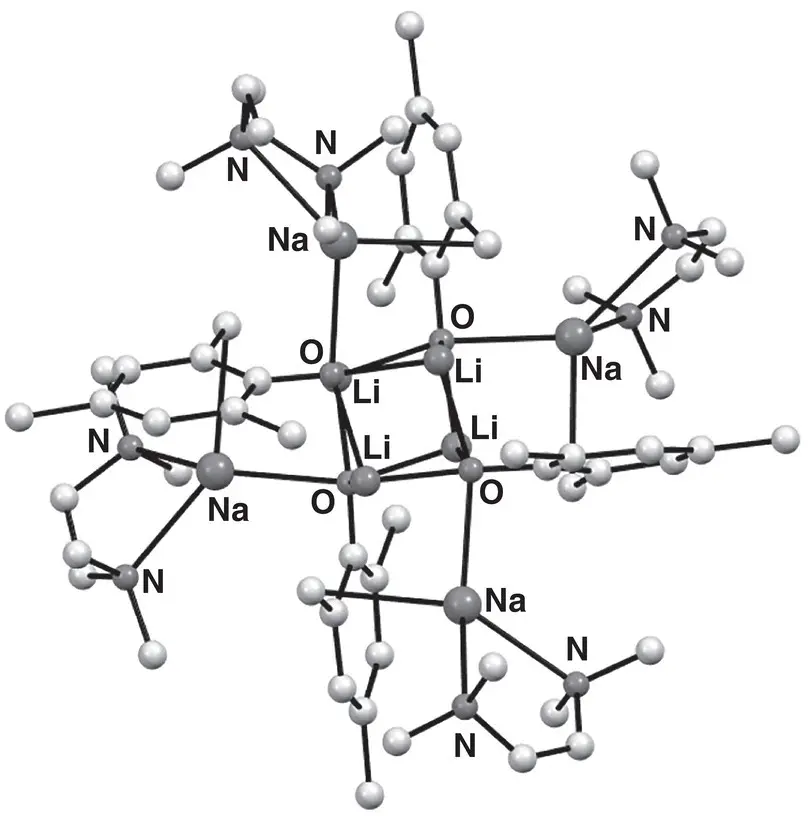

Structural information on superbases has been gathered from a number of areas. Concerning the activation of organolithium bases, early evidence for the existence of organolithium‐alkoxylithium aggregates of the type n ‐Bu xLi 4(OR) 4‐x(R = n ‐Bu or t ‐Bu; x = 1–4) in solution [51] was later substantiated by the crystallographic characterization of ( n ‐BuLi) 4(LiO t ‐Bu) 4 30[52]. This sparked a search for similar complexes capable of acting as structurally well‐defined models for superbases. Hence, alkoxy‐ and/or amido(alkali metal) combinations, now demonstrating the at least partial replacement of lithium with a higher group 1 congener, were investigated. These revealed not only a number of heterobimetallic structures [53] but also ternary alkali metal aggregates such as the twelve‐vertex cage [{PhN(H)} 2(O t ‐Bu)LiNaK(TMEDA) 2] 2 31 2( Figure 1.4a) [54]. However, whilst providing fascinating insights into alkali metal structural chemistry, their study has yet to allow a relationship to synthetically useful Li–K superbases to be established. A significant advance towards this was made with the study of the tetralithium–tetrapotassium amide‐alkoxide [{ t ‐BuN(H)} 4(O t ‐Bu) 4Li 4K 4(C 6H 6)](C 6H 6) 32( Figure 1.4b). Upon dissolution, crystals of this material achieved the smooth metalation of toluene [55]. Meanwhile, the combination of three alkali metal alkoxides yielded similar reactivity towards toluene through forming the fully characterizable ternary complex [Li 4Na 2K 2(O t ‐Bu) 8(μ‐L)] 33(L = η 6: η 6‐C 6H 6, TMEDA) at ambient temperature. In contrast, none of the individual alkali metal alkoxides MO t ‐Bu (M = Li, Na, K) or their binary combinations detectably reacted with toluene under the same conditions ( Scheme 1.9) [56].

Attempts to structurally investigate organo/alkoxy alkali metal aggregates, which might better represent the more frequently employed types of superbasic reagent already introduced [42, 43] have been hampered by the tendency of in situ preparations to precipitate microcrystalline (often organopotassium) products [57, 58]. Accordingly, a strategy was devised to overcome this problem through the in situ formation of a ligand providing both alkoxy and alkyl functionalities. To this end, sodium 2,4,6‐trimethylphenoxide was treated with n ‐BuLi to result in lateral sodiation, and this enabled the crystallization of [{4,6‐Me 2C 6H 2(O)(CH 2)}LiNa(TMEDA)] 4 34 4( Figure 1.5), in which each phenoxide ligand had undergone a single benzylic deprotonation [59]. Consistent with previous reports that Li–O bonding takes precedent over Na–O interactions (logically a reflection of hard/soft interactions) [54, 55], X‐ray diffraction revealed a structure based upon a (LiO) 4pseudocubic core, with the Na centres peripheral and coordinated perpendicular to the plane of the benzyl group.

Figure 1.4 Molecular structures of (a) [{PhN(H)} 2( t ‐BuO)LiNaK(TMEDA) 2] 2 31 2and (b) [{ t ‐BuN(H)} 4( t ‐BuO) 4Li 4K 4(C 6H 6)](C 6H 6) 32.

Sources : Adapted from Mackenzie et al. [54]; Kennedy et al. [55].

Scheme 1.9 Reactivity of metal alkoxides towards toluene in C 5D 5N. L = η 6: η 6‐C 6H 6, TMEDA; M, M' = Li, Na, K.

Figure 1.5 Molecular structure of [{4,6‐Me 2C 6H 2(O)(CH 2)}LiNa(TMEDA)] 4 34 4.

Source : Adapted from Harder and Streitwieser [59].

Moving forward a decade, the first organo/alkoxy Li–K species to be isolated from a LICKOR mixture was reported. To achieve this, n ‐BuLi‐KO t ‐Bu was reacted with C 6H 6in THF, yielding crystalline (PhK) 4(PhLi)( t ‐BuOLi)(THF) 6(C 6H 6) 2 35, an aggregate containing all the expected constituents of a superbase. Furthermore, its place in this family of reagents was confirmed by its ability to metalate toluene. From a structural perspective, in spite of the substoichiometric Li content of 35, interactions with the lighter alkali metal dominate: bonds from tert ‐butoxide and phenyl moieties are both shorter and more strongly directed towards Li +compared to peripheral K +, again likely reflecting a competing preference for hard/soft stabilization ( Figure 1.6) [60].

Whilst providing encouraging evidence for the reactivity of mixed Li–K species, the high potassium content of 35leaves some doubt surrounding its validity as a model superbase since pure PhK can achieve the same reactivity towards toluene [61]. However, further evidence for Li–K cooperativity has been gathered by the judicious choice of neopentyllithium (NpLi, Np = CH 2C(CH 3) 3) as a stable and hydrocarbon‐soluble alkyl equivalent. When partnered with t ‐BuOK, to form a LICKOR mixture, its use has allowed for the isolation of mixed‐metal aggregate Li 4K 4Np 2.75( t ‐BuO) 5.25 36[62]. Though detailed analysis of the structure was complicated by the positional disorder of the ligands and metal, the fundamental motif – a central, square planar arrangement of K centres, bicapped by [RLi(O t ‐Bu) 2LiR] 2⁻(R = Np/ t ‐BuO) – was clear ( Figure 1.7a). Meanwhile, the NMR spectroscopic monitoring of experiments in which the NpLi : LiO t ‐Bu : KO t ‐Bu ratio was varied revealed evidence for equilibria involving Li‐rich mixed Np/O t ‐Bu species (represented by the series Li 4K 3Np x(O t ‐Bu) 7‐ x) in solution. In this work, the excess of Li could be rationalized by the tendency of poorly soluble NpK to precipitate. Consistent with this, cooling solutions rich in Np ⁻led to crystallization of the Li‐rich mixed metal species, Li 4K 3Np 3.16(O t ‐Bu) 3.84 37. X‐ray diffraction exposed in this the coordination of alkyl moieties to both K and Li centres ( Figure 1.7b). This suggested hybrid Li/K–C bond polarity, which was in turn postulated to be responsible for superbasic activity.

Recently, this work has been extended to examine other Li–K compounds of the type described above, whose compositions are dominated by either metal. Thus, the structure of Li 4KNp 2(O t ‐Bu) 3 38has been elucidated in the solid‐state, revealing a square pyramidal metal architecture wherein interaction of apical K with the CH 3component of an Np unit in an adjacent monomer results in a solid‐state dimer ( Figure 1.8) [63]. Meanwhile, exploring K‐rich end members has lately provided the first crystallographic evidence for the existence of a mixed organo/alkoxypotassium species, K 4Np(O t ‐Am) 3 39( t ‐Am = CH 2C(CH 3) 2CH 2CH 3). Based on its favourable solubility profile and donor solvent‐free constitution, reactivity comparable with or superior to organopotassium reagents was anticipated. In the event, this was realized in the polymetalation of ferrocene. Though isolation of metalated intermediates was not possible, the regioselectivity of metalation could be competently assessed through the study of carboxylated intermediates and the crystallization of selected ferrocene methyl ester derivatives ( Scheme 1.10).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Polar Organometallic Reagents»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Polar Organometallic Reagents» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Polar Organometallic Reagents» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.