Figure 2.3 Verticality and horizontality of the continents

Reproduced using map in Diamond (1997). Gall-Peters map projection.

This, according to Diamond, was why the Near East was the birthplace of human civilization. It was in the Near East that wheat, barley, and the pea were first cultivated. The rich fertile plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were surrounded on several sides by so-called “hilly flanks.” Goats and sheep were first domesticated 11,000 years ago in the hills of northern Syria and northern Mesopotamia. Pigs and cattle followed soon afterwards and spread throughout the Fertile Crescent. In total, thirty-three of the world’s fifty-six heaviest wild grasses originated in either Europe, the Near East, or North Africa. The majority of these crops were first domesticated in the Fertile Crescent. Moderate climatic differences between Europe and the Middle East ensured that agricultural techniques could spread between the two.

Of the fourteen species of large domesticable animals, only one, and perhaps the least useful – the llama – originated in the New World. Nine of the world’s fourteen large domesticable herbivores originated in Eurasia. This left inhabitants of the New World at a decided economic disadvantage. Livestock are a tremendous source of both animal power and protein. But domesticated animals are also a source of epidemic disease. The absence of large domesticable animals left New Worlders particularly vulnerable to new diseases. Because interactions between humans and animals are a major source of epidemic disease, human populations which have a long history of exposure to these diseases are more likely to acquire immunity. This is why contact with Europeans was so deadly for Native Americans. Recent estimates suggest there was a 95–98% drop in the Native American population between its pre-1492 peak and 1900 (Mann, 2005).

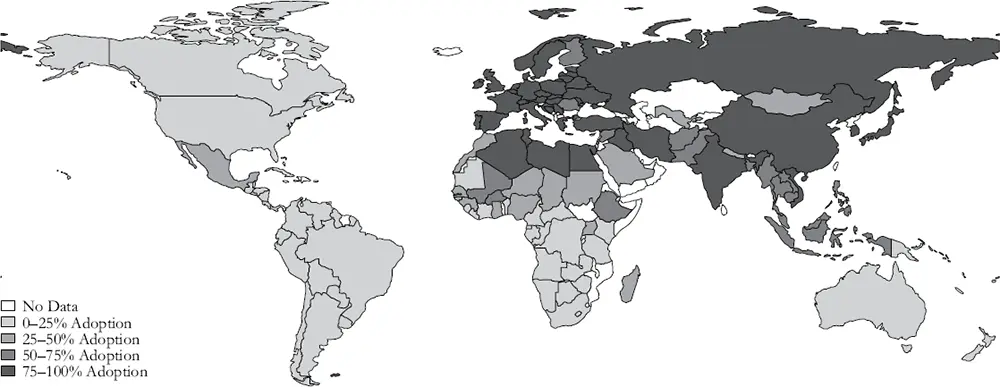

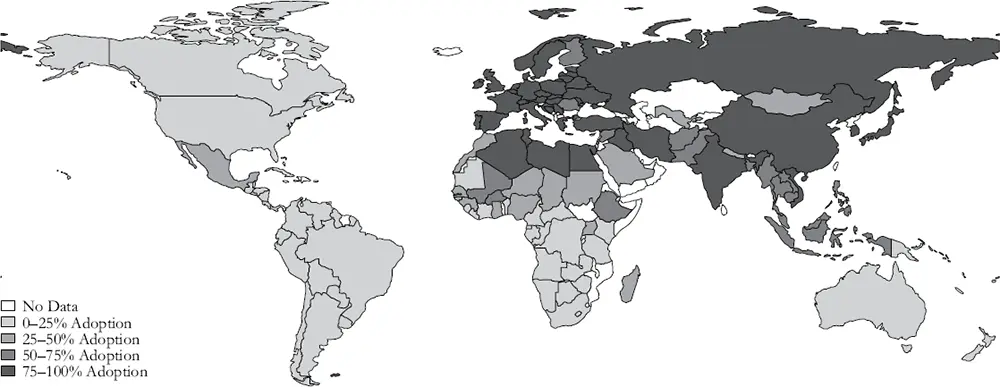

Figure 2.4 Technology adoption levels in 1500 (% of frontier technologies adopted)

Data source : Pavlik and Young (2019).

Diamond’s arguments about the diffusion of technologies across regions have received empirical support. Pavlik and Young (2019) find that technologies moved more easily between east–west neighbors than between north–south neighbors. This is plainly seen in Figure 2.4, which maps how close to the technological frontier different parts of the world were in 1500. On the eve of the European discovery of the Americas, the technology of the Eurasian east–west axis was clearly more advanced than that of the American north–south axis or that of the sub-Saharan Africa north–south axis. These differences would only become exacerbated with the onset of colonization (see Chapter 6).

Mountains, Coasts, and Climate

Markets are unlikely to exist where it is difficult to transport goods and people. Geography is thus an important determinant of market size today (Redding and Venables, 2004). It mattered even more in the pre-industrial period. Prior to the spread of the railroad in the mid-19th century, water transport was by far the most cost-effective way to transport goods from one place to another. It was often twenty times cheaper to transport a good by sea than by land. So, it is reasonable to suspect that access to navigable waterways was historically an important component of economic growth.

Venice and the Low Countries provide instructive examples. Both were among the centers of commerce in late medieval Europe. Neither were ideal places to set up cities. Both were established on marshlands that required heroic feats of hydraulic engineering just to be viable (and, for this reason, both are in danger if sea levels rise too much in the 21st century). Why did people not only inhabit these regions but thrive while doing so? Access to water is one clear answer. The Low Countries have numerous ports that spilled out into the lucrative North Sea trade. Venice is on the Adriatic Sea, giving it prime access to the Mediterranean. But access to water is likely not the only reason people settled there. Montesquieu speculated that trade first developed in marginal lands where the land was unproductive and where individuals only settled because they were fleeing violence and predation. Indeed, it is these factors that are often emphasized in tales of the founding of Venice.

Another important geographic factor is ruggedness – how mountainous a particular territory is. Rugged terrain impedes trade and communication. This barrier was especially severe in pre-industrial times prior to the invention of the automobile, steam engine, and airplane. Japan, for example, is highly mountainous. Only a tiny fraction of the Japanese islands are suitable for rice cultivation or are possible locations for cities. Mountain ranges form a spine running through the country. This very well may have held Japan back. Yet, as we discussed in Chapter 1, although rugged terrain is usually seen as a major impediment to economic development, Nunn and Puga (2012) highlight the blessing of bad geography in sub-Saharan Africa. Historically, rugged territories were less likely to suffer the predation of slavers. Hence areas with “bad” geography in sub-Saharan Africa are richer rather than poorer today.

The quotes cited at the beginning of the chapter from Abū al-Qāsim Sā’id and Montesquieu argued that one reason why geography mattered was climate. Climate, unlike other geographic characteristics, is not fixed, however. For example, the climate of the Mediterranean was both warmer and wetter around 0 CE. Solar activity was high and stable. Evidence from tree rings and ice cores suggests that the 1st century CE was warmer than even the last century and a half (since 1850) (Manning, 2013). Consequently, the land available for agriculture expanded. Ancient historians like Harper (2017) link this Roman Climatic Optimum to the rise of the Roman Empire.

Wheat agriculture is highly sensitive to temperature. Warm growing-season temperatures are especially critical. The downside to higher temperatures is aridity and the risk of drought. The Roman warm period, however, was also wetter. This environment made it possible for Romans to expand the cultivation of Mediterranean crops inland into mountainous terrain. According to Harper (2017, p. 53) this warmth “was the enabling background of the Roman miracle…. If we only count the marginal land rendered susceptible to arable farming in Italy by higher temperatures, on the most conservative estimates, it could account for more than all of the growth achieved between Augustus and Marcus Aurelius” (that is, between c. 0 and c. 150 CE).

The passing of the Roman Climatic Optimum was associated with political crises. Periods of lower rainfall, especially in the 3rd century CE, were associated with military mutinies and imperial assassinations (Christian and Elbourne, 2018). Similarly, colder and more volatile weather together with the spread of epidemic disease helped to account for the failed attempts to rebuild the Roman Empire. Volcanic eruptions possibly led to what is known as the “Year without Sun” (536 CE). The century that followed has been called the Late Antique Little Ice Age. Although historians no longer use the term “the Dark Ages” to describe the early Middle Ages, the phrase does capture something vivid about how possibilities narrowed after 550 CE (Ward-Perkins, 2005).

Climatic change also played a role in the revival of the European economy after 1000. Cultivated land expanded. Vineyards proliferated in England. Iceland and Greenland were settled by Vikings. In Chapter 3, we discuss the period of economic expansion – known as the Commercial Revolution – that occurred between 1000 and 1300, during a period of unusually warm weather (Lamb, 1982). Institutional innovations were critical. But the climate was an important enabling condition. Similarly, populations and cities expanded in Southeast Asia and in North America in this period before collapsing in the late 13th and 14th centuries (Richter 2011, pp. 11—36; Reid 2015, pp. 50–6).

Читать дальше