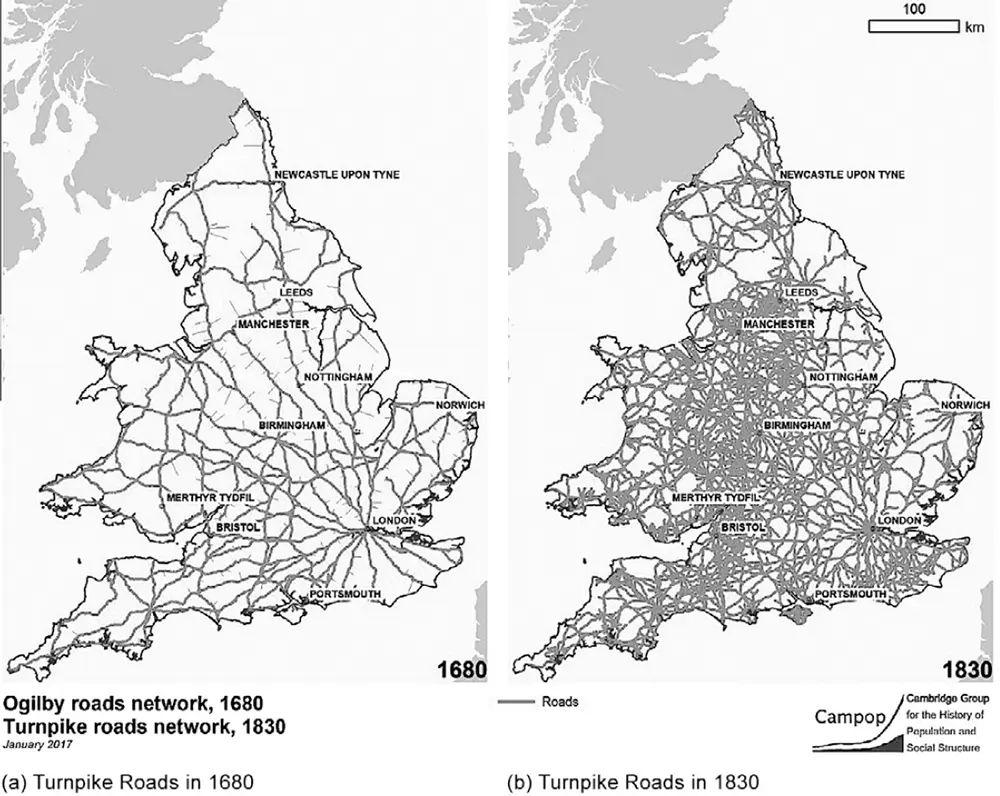

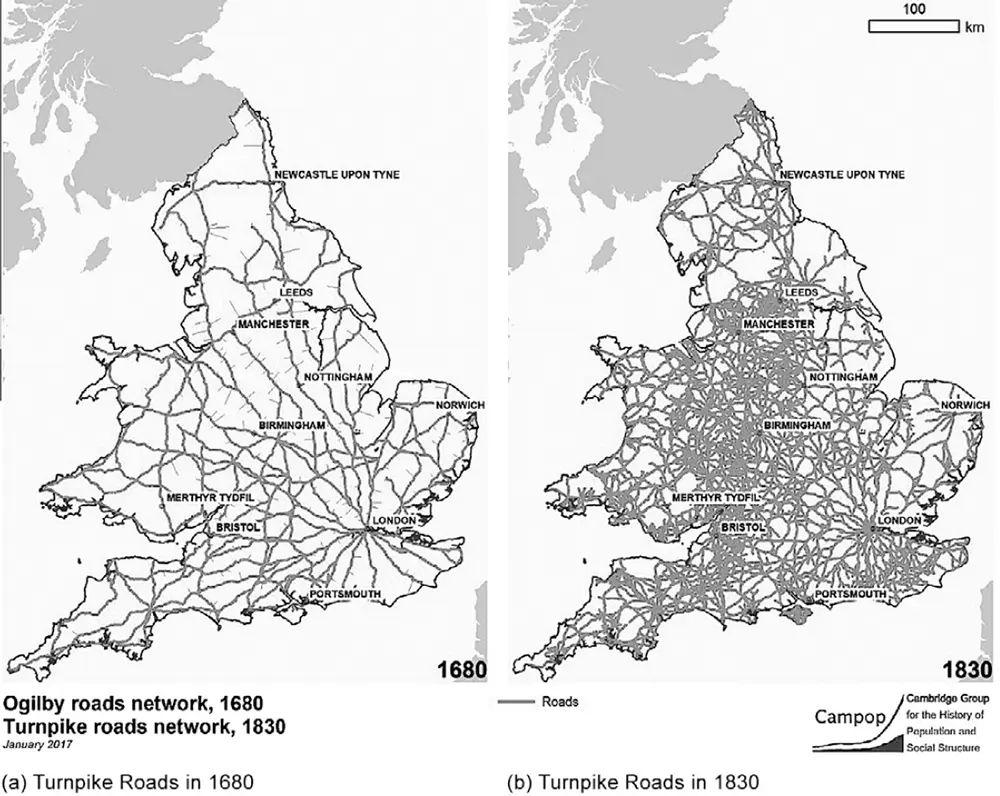

The story of these investments in transport infrastructure is partly technological and partly institutional. The institutional part of the story will be discussed in Chapter 3. Here, we focus on the consequences of these improvements. Stagecoach speeds increased from 1.96 journey miles per hour in 1700 to 7.96 journey miles per hour in 1820. This was due to improvements in the road network, stagecoach design, and the number of way-stations. By 1840, Britain had twice the road density of France or Spain. Figure 2.7 depicts the expansion of the road network in England and Wales. The greatest improvement in land transportation came with the railway: rail travel in 1870 was ten times faster than coach travel had been in 1700. Goods, ideas, and people could move across Britain in a way and at a speed that had previously been impossible.

Another major area of improvement in industrializing Britain was the canal network. Waterborne transport was much more cost-efficient than road transport. Canals played an important role in linking together Britain’s growing industrial heartland in the northwest with coal.

This transportation revolution had a dramatic impact on the British economy. Bogart, Satchell, Alvarez-Palau, You, and Taylor (2017) find that improvements in turnpike roads and inland waterways played a key role in driving population growth and structural change. Locations further away from turnpikes and canals grew more slowly. They also remained more agricultural than those closer to the improving transport network.

Figure 2.7 The increase in turnpikes in England and Wales: 1680–1830

Map provided by Dan Bogart from Bogart, Satchell, Alvarez-Palau, You, and Taylor (2017). Lines represent turnpike roads in 1680 (panel a) and 1830 (panel b).

One of the challenges in measuring the benefits of infrastructure investment is that beyond the direct effects of lowering transport costs, there are numerous (potentially important) but difficult to measure indirect effects. We can think about these improvements through the concept of market access, which summarizes all the ways both goods and factor markets – that is, markets for labor, land, and capital – change in response to a change in transport technology or infrastructure.

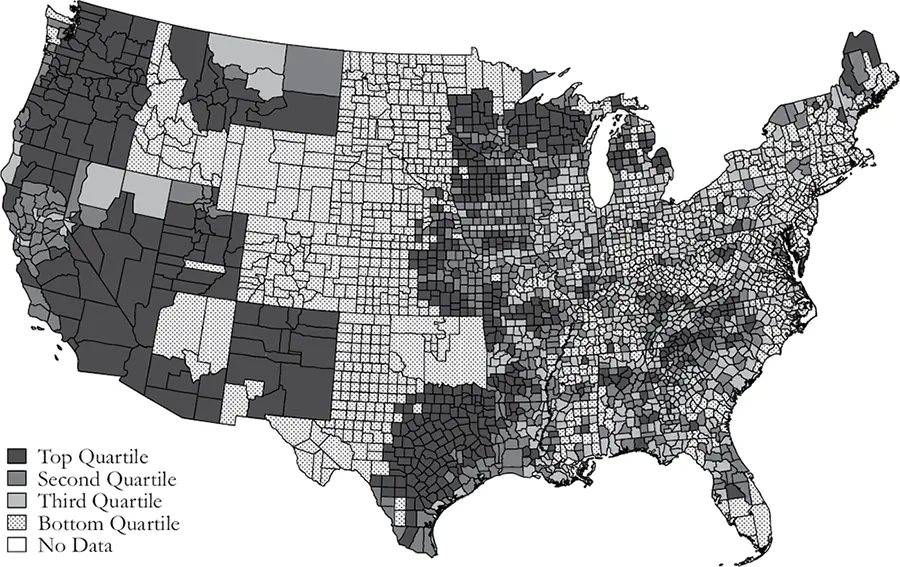

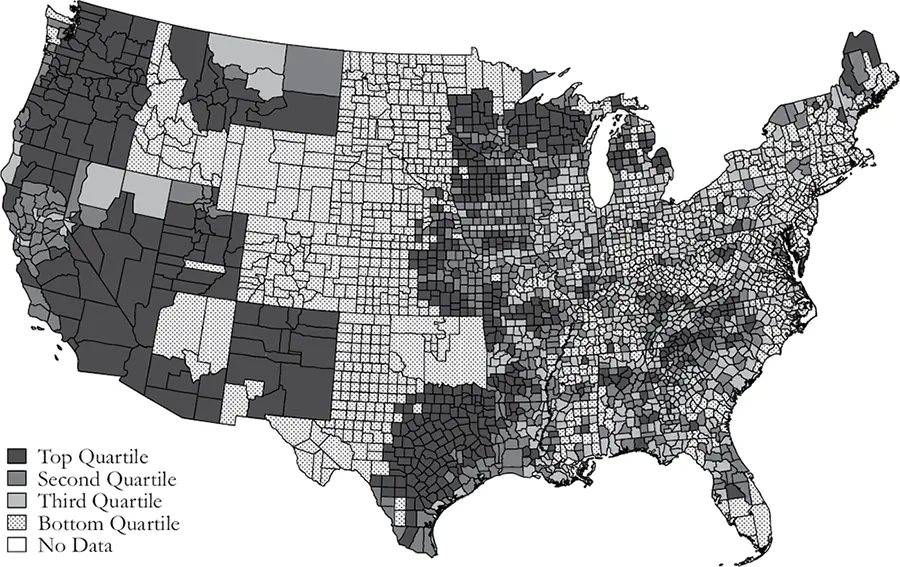

In an influential book, Fogel (1964) argued that the benefits of the railroad to American growth were modest because in its absence other transportation techniques such as waterways and canals would have been used. However, Donaldson and Hornbeck (2016) show that once the improvements to market access are taken into account, the railroad did have a more sizable impact on economic growth, especially during the rapid period of railroad expansion in the late 19th century. This was most pronounced in the Western states, which became more closely connected with the larger markets on the Eastern seaboard (see Figure 2.8). Donaldson and Hornbeck find that removing all railroads in 1890 would have decreased the value of agricultural land by 60.2%, which translates to 3.22% of GNP.

Figure 2.8 Changes in US market access, 1870–90

Data source : Donaldson and Hornbeck (2016).

Moreover, Hornbeck and Rotemberg (2021) show that railroad access greatly increased US manufacturing output. They estimate that US aggregate productivity would have been 25% lower in 1890 in the absence of railroads. In the context of Industrial Revolution Britain, Bogart, Alvarez-Palau, Dunn, Satchell, and Taylor (2017, p. 23) find that improved market access had a direct effect on population growth. Had there been no improvements in transportation, there would have been 25 percentage points less urban growth between 1680 and 1831 and 97 percentage points less growth from 1831 to 1851. These are enormous numbers. They indicate just how important transport improvements were for the growth of the British and US economies.

Donaldson (2018) employed a similar methodology to examine the building of railroads in India under the British Raj. Transport investments made it possible to transport bulky goods such as wheat and rice over land as much as twenty times faster than had been possible with pre-industrial technologies. The railroad network thus brought regions of India out of near autarky, integrating them with the rest of the country and the world.

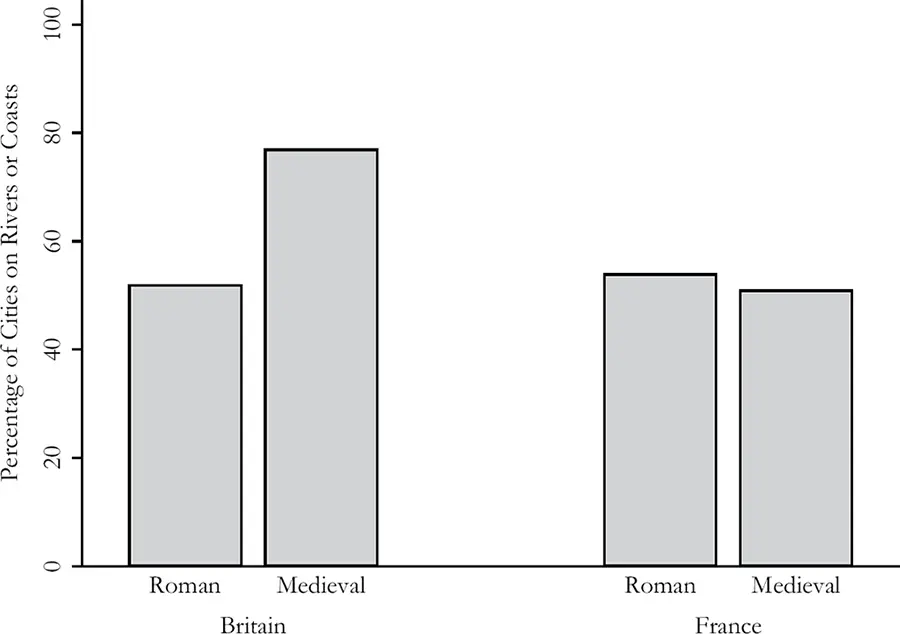

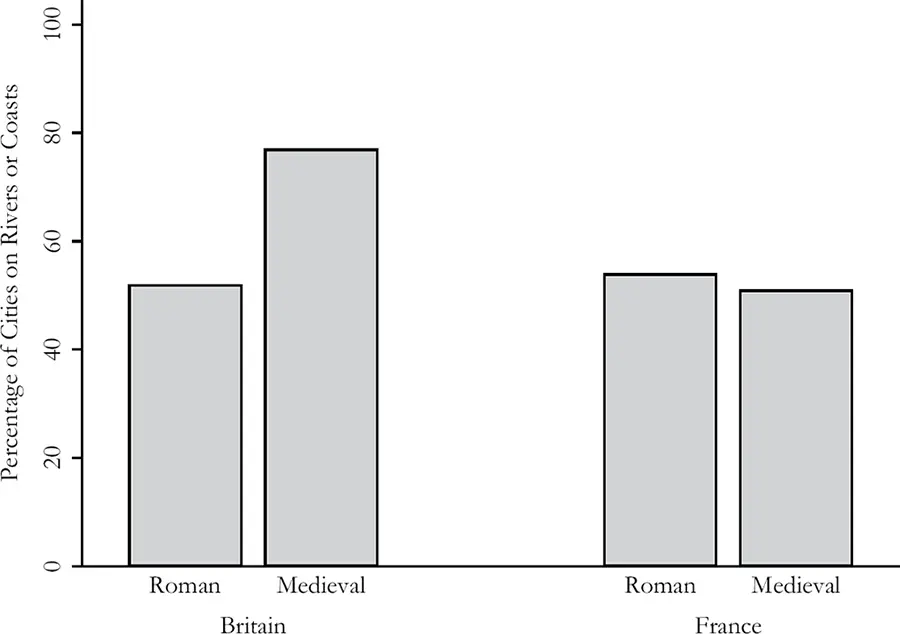

Infrastructure investments can help overcome the “curse of geography.” But they can also have unforeseeable, counter-productive effects in the long run. For instance, prior investments in transport can lock countries into particular, and potentially inefficient, economic configurations. A fascinating example of such lock-in comes from the western part of the Roman Empire. Michaels and Rauch (2018) contrast England with France. In France, Roman city locations remained settled throughout the early Middle Ages. Michaels and Rauch show that while this may have benefited French economic growth in the early medieval period, it harmed it in the long run. Because French cities were placed with access to Roman roads in mind, they were inferior from the point of view of subsequent economic development, where water travel dominated. In England, however, the urban network was reset following the collapse of the Roman Empire. This allowed medieval English cities to relocate along coasts and rivers that were more beneficial for economic activity in subsequent centuries (see Figure 2.9).

Geography and Industrialization

This chapter opened with the question: is geography fate? We have shown that geography is not fate, but there are important instances where it undoubtedly matters for economic outcomes. The final question we address in this chapter is: can geography help explain why and where the Industrial Revolution took place? Can the logic of Diamond’s argument in Guns, Germs, and Steel be used within Eurasia to explain why industrialization first took off in Western Europe and not China, the Middle East, or elsewhere?

Within Eurasia, it has been suggested that Europe’s geographic position made it more likely to discover the Americas and benefit from Atlantic trade (Fernández-Armesto, 2006). Within Europe itself, however, access to the Atlantic

Figure 2.9 Location of cities in England and France in the Roman and medieval periods

Data source : Michaels and Rauch (2018).

was a mixed blessing. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2005 b ) studied the impact of Atlantic trade on European economic development. They found that the discovery of the Americas and the development of new trade routes had varying effects on economic growth, depending on the society’s political institutions. In other words, geography played a role in determining economic outcomes via its effect on institutions. Where long-distance commerce was already controlled by the crown, access to the Atlantic strengthened royal power. Two prominent examples of this are Charles V and Phillip II, who ruled Spain for most of the 16th century. Access to the Atlantic – and all of the wealth flowing from South American mines – allowed them to dispense with representative institutions. Thus, while Spain was initially enriched by the Americas, the long-run impact on economic growth was negative, since it resulted in more extractive institutions. In contrast, where monarchs lacked the ability to control or monopolize long-distance trade (such as in England or the Dutch Republic), the discovery of the Americas strengthened the merchant class and enabled them to constrain royal power. We discuss this point in more detail in Chapter 7.

Читать дальше