People are … more vigorous in cold climates…. The inhabitants of warm countries are, like old men, timorous; the people in cold countries are, like young men, brave. If we reflect on the late wars … we shall find that the northern people, transplanted into southern regions, did not perform such exploits as their countrymen who, fighting in their own climate, possessed their full vigor and courage. (Montesquieu, 1748/1989, p. 317)

Modern scholars have also argued that geography and climate play a crucial role in explaining patterns of economic development. Perhaps the most well-known insights are those of Diamond (1997), who argues that factors like the relative length of continental axis, the disease environment, proximity to the equator, and access to coasts and rivers had a tremendous influence on long-run economic prosperity. We discuss Diamond’s influential hypothesis in depth in this chapter.

But is geography fate? Are locations with “good” characteristics destined to be more developed? Davis and Weinstein’s (2002) seminal study of Japanese urban development in the aftermath of World War II provides evidence for the importance of geographic fundamentals. The authors examined what happened to the distribution of urban centers after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the atomic bomb. They show that after experiencing complete destruction, both Hiroshima and Nagasaki returned to the same relative positions in Japan’s distribution of cities within twenty years. This suggests that a major shock to the distribution of population was insufficient to overcome the intrinsic geographic advantages of these two locations. Whether such findings are generalizable is something we will discuss throughout the book.

What about the Industrial Revolution? Britain’s position as a large island off the coast of Europe, endowed with a moderate climate, numerous rivers, and a long coastline, helped shape the formation of its political institutions. Abundant coal resources played an important role in its early industrialization. It is worth asking: could this be why Britain industrialized first?

Geography and Modern Development

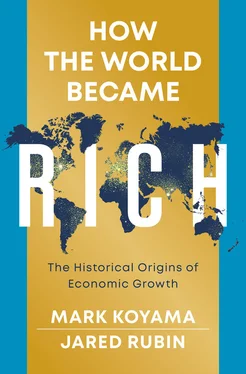

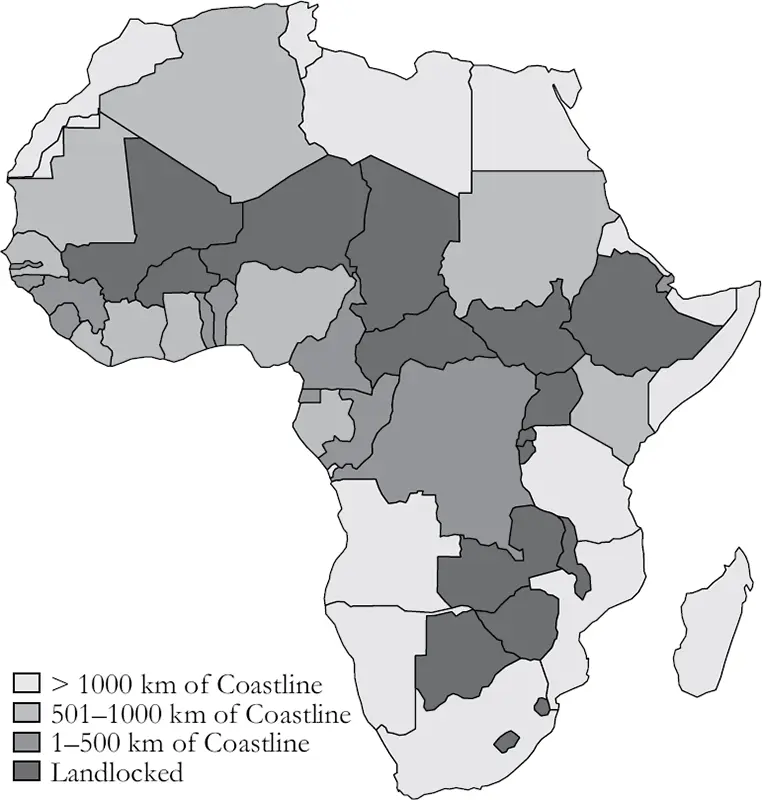

Geography matters for economic development today, especially in the poorest parts of the world. For instance, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are landlocked, and most others have only a small amount of coast (see Figure 2.1). Without coastlines, they are unable to directly ship goods to other countries. They also have to rely on expensive and hard-to-maintain road and rail networks which can easily be blocked or cut off by their neighbors.

Figure 2.1 Coastlines of African countries

Coast length data from: CIA (2019).

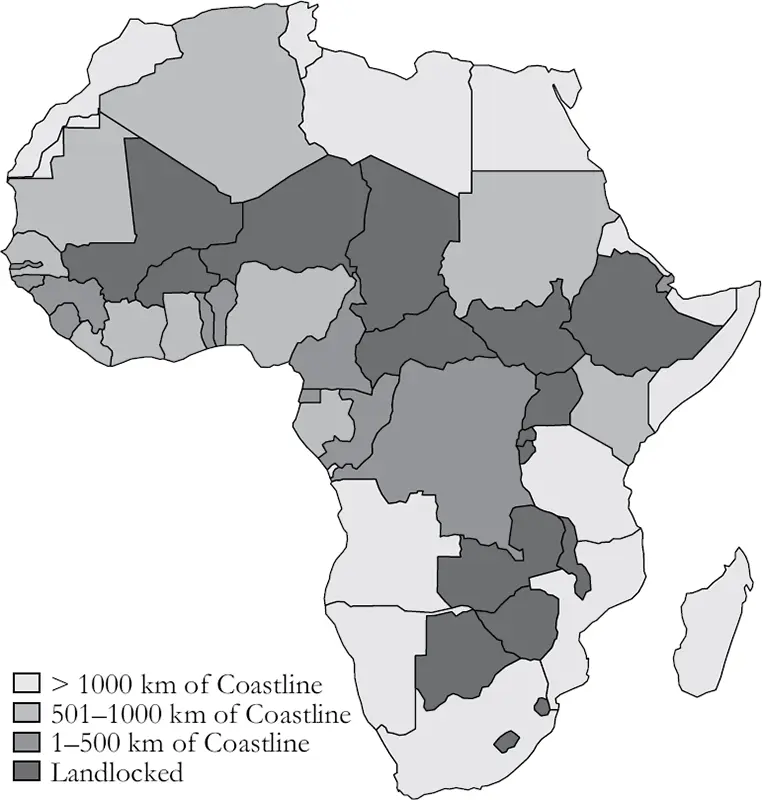

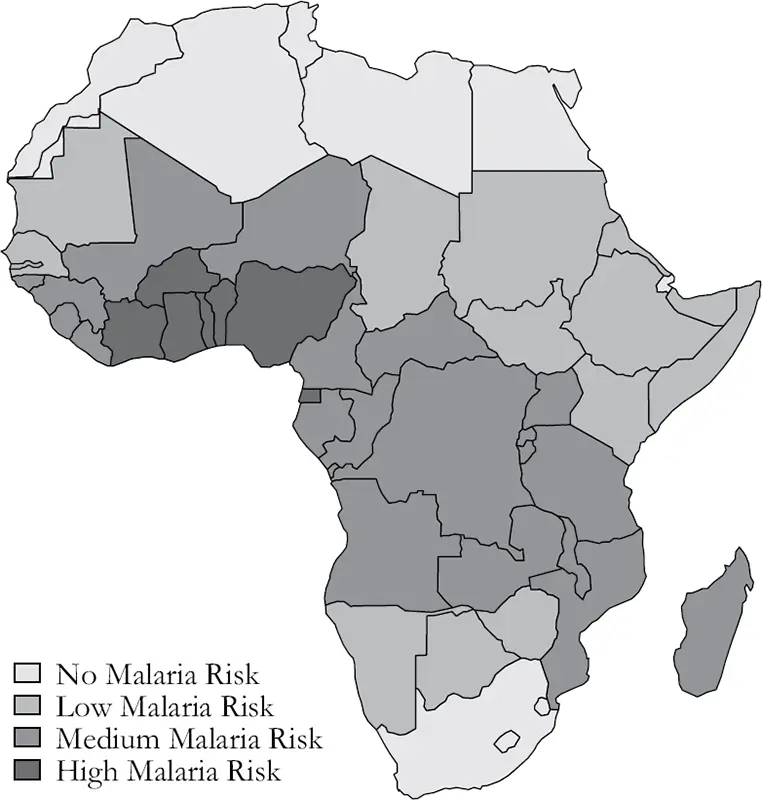

Figure 2.2 Africa’s “malaria belt”

Data source : Hay, Guerra, Gething, Patil, Tatem, Noor, et al. (2009).

Another important geographic factor is disease burden. Countries in the “malaria belt” in sub-Saharan Africa continue to be underdeveloped (see Figure 2.2). Malaria has probably killed more human beings over the course of human history than any other disease. But the burden of malaria is also economic. All else being equal, countries where a high proportion of the population are infected with malaria had growth rates that were around 1.3% lower than other countries (Sachs and Malaney, 2002). They also have higher infant mortality and lower investment in physical and human capital.

Other diseases are also endemic in sub-Saharan Africa. One particularly potent disease is sleeping sickness, which the tsetse fly transmits via parasites. The effects of the tsetse fly are not limited to humans. The same parasite causes nagnana, which is deadly to livestock. Livestock played a crucial role in agricultural development in other parts of the world. People in regions affected by the tsetse fly were historically much less likely to domesticate livestock. Alsan (2015) documents how in these parts of sub-Saharan Africa, intensive agriculture was less likely to develop, the plow was less likely to be employed, and large domesticated animals were rarer. These patterns of economic underdevelopment also had political consequences, as they made it less likely for centralized states to develop.

These examples point to the attractions and limitations of arguments based on geography. On the one hand, geography-based arguments are simple and geography has the advantage of being largely exogenous. This means that it is not affected by other variables of interest. As such, we don’t have to worry about geography being the result of other factors that are also important for economic growth, such as culture or institutions. Hence, geographic explanations can potentially provide a straightforward explanation of economic growth and poverty.

The big problem with geographic explanations, however, is that geography is largely unchanging. Geography is not completely static, of course. For instance, fisheries can be over-fished, and this encourages societies to adapt accordingly (Ostrom, 1990; Dalgaard, Knudsen, and Selaya, 2020). And natural resources are generally not just there for the taking – finding them requires exploration and the capacity to extract (David and Wright, 1997). But geography is much less malleable than other societal features such as demography, institutions, or culture. This can be a problem for explanations linking geography to long-run economic growth, because many of the differences in incomes that we observe across the world today have changed dramatically over time. In 1750, the richest country in the world (per capita) was probably the Dutch Republic. Yet, it was only at most four times richer than the poorest countries in the world. Today the richest countries in the world are between one hundred and two hundred times richer in terms of measured GDP per capita. More perplexing still, geography has a difficult time explaining economic reversals. As it is mostly fixed, it cannot easily explain why the Middle East was much more developed in 1000 than Western Europe yet by 1800 Western Europe was far ahead of the Middle East.

Guns, Germs, and Steel

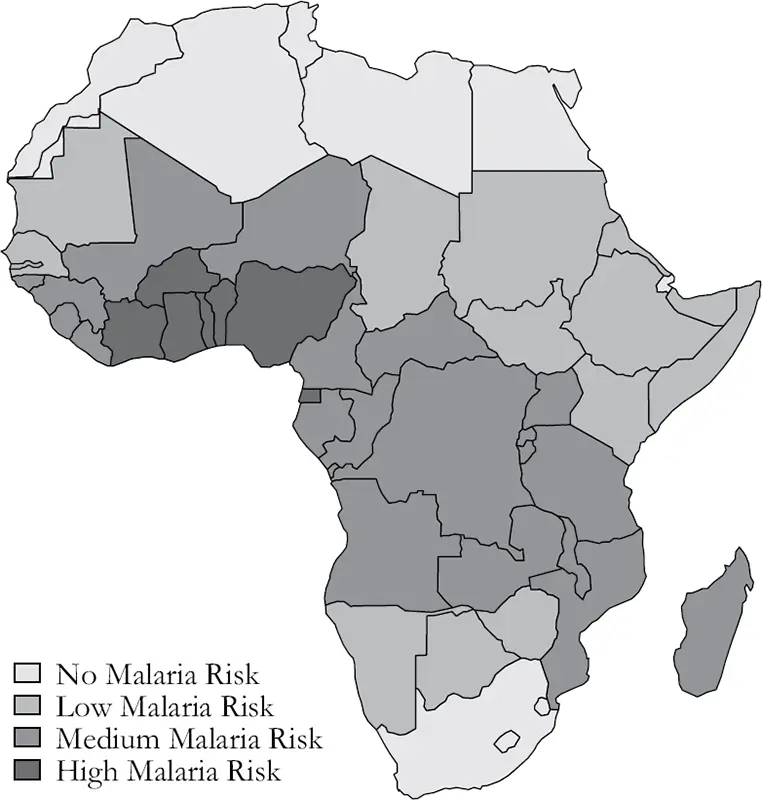

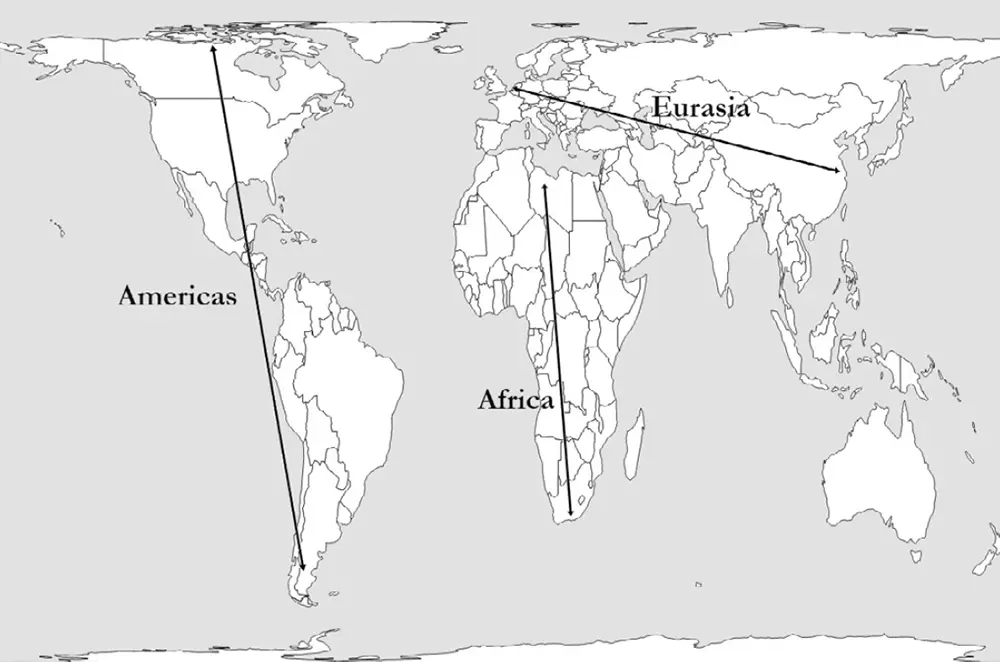

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Guns, Germs, and Steel , Diamond (1997) asked why it was that Europeans were able to conquer the New World so easily. How was it that they had not only superior weapons and technology but also more deadly germs than the native inhabitants of the Americas? His answer was geography. To explain why Eurasian societies were more technologically advanced, he drew on the work of Crosby (1986), who argued that the relative height and length of the Eurasian, African, and American continents had a deep impact on long-run development. Vertically aligned continents contain numerous microclimates, which limit the spread of crops, domesticated animals, and people. After all, crops suitable for rain forests are unlikely to grow in the savannah or mountains. So, the domesticated plants and animals of Mesoamerica did not spread to Peru or the Amazon basin. Perhaps more importantly, technology and knowledge spread more easily horizontally than vertically, since climatic characteristics vary less. The “verticality” of the Americas and Africa south of the Sahara (see Figure 2.3) may have therefore imposed huge hurdles to long-run economic growth.

Читать дальше