I Didnât Do It For You

How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation

Michela Wrong

To Elena and Silvia Harty, as promised

Cover Page

Title Page I Didnât Do It For You How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation Michela Wrong

Dedication To Elena and Silvia Harty, as promised

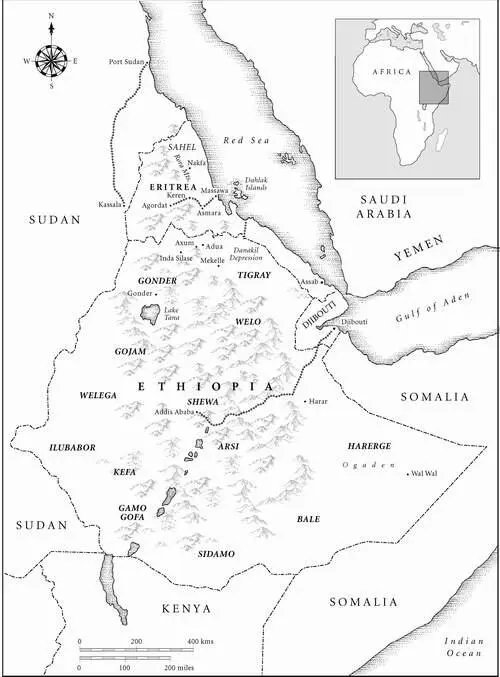

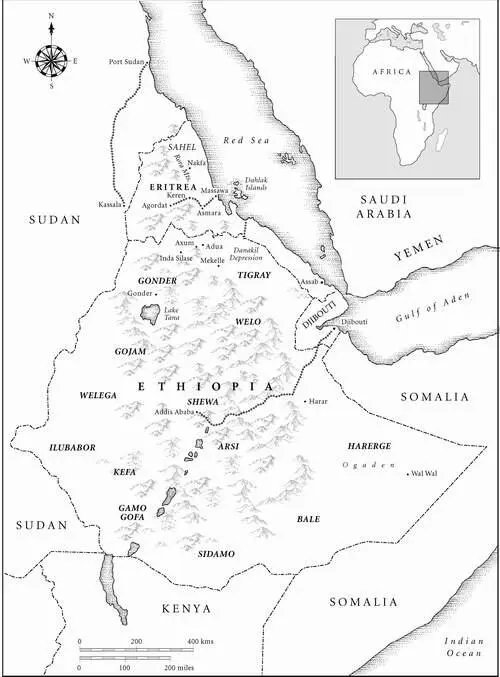

Maps Maps EritreaâEthiopia border as defined by the International Boundary Commission on April 13, 2002 EritreaâEthiopia border as defined by the International Boundary Commission on April 13, 2002

Foreword

CHAPTER 1 The City Above the Clouds

CHAPTER 2 The Last Italian

CHAPTER 3 The Steel Snake

CHAPTER 4 This Horrible Escarpment

CHAPTER 5 The Curse of the Queen of Sheba

CHAPTER 6 The Feminist Fuzzy-Wuzzy

CHAPTER 7 âWhat do the baboons want?â

CHAPTER 8 The Day of Mourning

CHAPTER 9 The Gold Cadillac Site

CHAPTER 10 Blow Jobs, Bugging and Beer

CHAPTER 11 Death of the Lion

CHAPTER 12 Of Bicycles and Thieves

CHAPTER 13 The End of the Affair

CHAPTER 14 The Green, Green Grass of Home

CHAPTER 15 Arms and the Man

CHAPTER 16 âWhere are our socks?â

CHAPTER 17 A Village of No Interest

CHAPTER 18 âItâs good to be normalâ

Chronology

P.S. Ideas, interviews & features â¦

Interview

About the book

Read on

Glossary and acronyms

Notes

Other sources

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

EritreaâEthiopia border as defined by the International Boundary Commission on April 13, 2002

EritreaâEthiopia border as defined by the International Boundary Commission on April 13, 2002

It was well past midnight, and in Cairo airportâs transit lounge it was clear most passengers had already entered the trance-like state of passivity that accompanies long-distance travel. Outside, in the fluorescent glare of the hallway, a trio of stranded Senegalese women traders, majestic in their colourful boubous, were shouting, with operatic volume, at the Egyptian airport staff behind the counter, who were responding with an icy silence that said more about Arab attitudes towards black Africa than direct insults ever could. But here in transit, eyes had glazed over, the energy had leached from the air. A group of Nigerian youths, whose clothes gave off the nose-tickling aroma of dried fish, lay slumped in the plastic orange scoop seats, spines turned to jelly. They were being messed around by EgyptAir staff, who couldnât be bothered to check them in to the airport hotel their tickets entitled them to. They seemed past caring, anger had long since given way to exhaustion.

A few seats away, a middle-aged Pakistani businessman was fighting the prevailing mood of stupefied indifference. Visiting cards at the ready, he was in defiantly chatty mode, and was taking the fact that the airline had mislaid his luggage in his stride. (âEgyptAir no good,â he confided. âHmm, yes, I know.â) He worked for a company that manufactured soap powder, he said, and constantly travelled the African continent and the Middle East, sizing up possible markets for his multinational.

âAnd you, what do you do?â

âIâm a journalist. Iâm writing a book about Eritrea. Thatâs where Iâm going now.â

His brow furrowed, he must have misheard. âYou are writing a book about Algeria?â

âNo, not Algeria. Eritrea.â

âNigeria?â He was floundering now.

âNo.â

A wild guess. âAl-Jazeera?â

âNo, no. Eritrea .â Enunciating the word with the exaggerated lip movements of a teacher addressing a class with special needs, I searched for some explanatory shorthand. âYou know. Small country on the Red Sea. Used to be part of Ethiopia. Itâs only two hoursâ flight from here. Iâm waiting for my connection.â

There was a brief silence. This seasoned traveller looked both flummoxed and embarrassed. âIâm sorry. But Iâve simply never heard of the place.â

It was a conversation that was to keep recurring throughout the four years I spent writing this book. Mention that I was researching Eritrea and the reaction would be a sympathetic nod and ruminative silence as the other person tried to work out whether I was talking about a no-frills airline, a Victorian woman novelist or, perhaps, some obscure strain of equine disease. The same ignorance, I discovered, extended to the written record. I read books on Art Deco and Modernist architecture that made no mention of the city of Asmara, containing some of the worldâs most perfect examples of the styles. I waded through weighty accounts of the American intelligence services that either never referred to the fact that Eritrea had been the site of one of Washingtonâs key listening posts, or dismissed it in a few paragraphs. I dusted off biographies on the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst that treated her involvement in the Horn of Africa as little more than an eccentric coda to her life. Whether in conversation or in print, Eritrea rang few bells.

At first, it amused me, then, slowly, it began to irritate. My annoyance grew in parallel with my knowledge, for the deeper I delved, the clearer it became that Eritrea had never been the obscure backwater suggested by the polite, blank expressions. Its narrative was entwined with those of colonial empires and superpowers, its destiny had engaged presidents in the White House and leaders in the Kremlin. It had obsessed emperors who believed themselves descended from Solomon and preoccupied dictators who took the Fascist salute.

I became increasingly defensive as I staked out claims to relevance, spelling out links and liaisons obliterated by the passage of time. âYou know, we ran the place for ten years,â I would say, talking to a fellow Briton. Or, if it was an American: âActually, the US had one of its most important spy bases in Eritrea during the Cold War.â As for the Italians, I heard myself speaking with the fixed-eye testiness of someone lost in a private obsession: âIt was your oldest colony, your âfirst-bornâ. Didnât they teach you that at school?â

History is written â or, more accurately, written out â by the conquerors. If Eritrea has been lost in the milky haze of amnesia, it surely cannot be unconnected to the fact that so many former masters and intervening powers â from Italy to Britain, the US to the Soviet Union, Israel and the United Nations, not forgetting, of course, Ethiopia, the most formidable occupier of them all â behaved so very badly there. Better to forget than dwell on episodes which reveal the victors at their most racist and small-minded, cold-bloodedly manipulative or simply brutal beyond belief. To act so ruthlessly, yet emerge with so little to show for all the grim opportunism; well, which nation really wants to remember that?

The problem, as the news headlines remind us every day, is that while the victims of colonial and Cold War blunders do not pen the story that ends up becoming the worldâs collective memory, they also donât share the conquerorsâ lazy capacity for forgetfulness.

Читать дальше