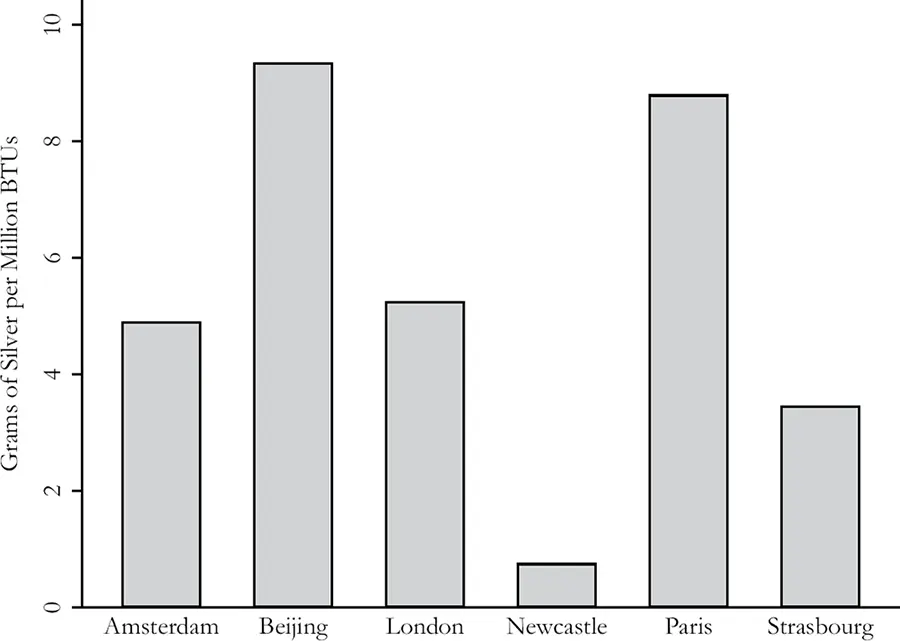

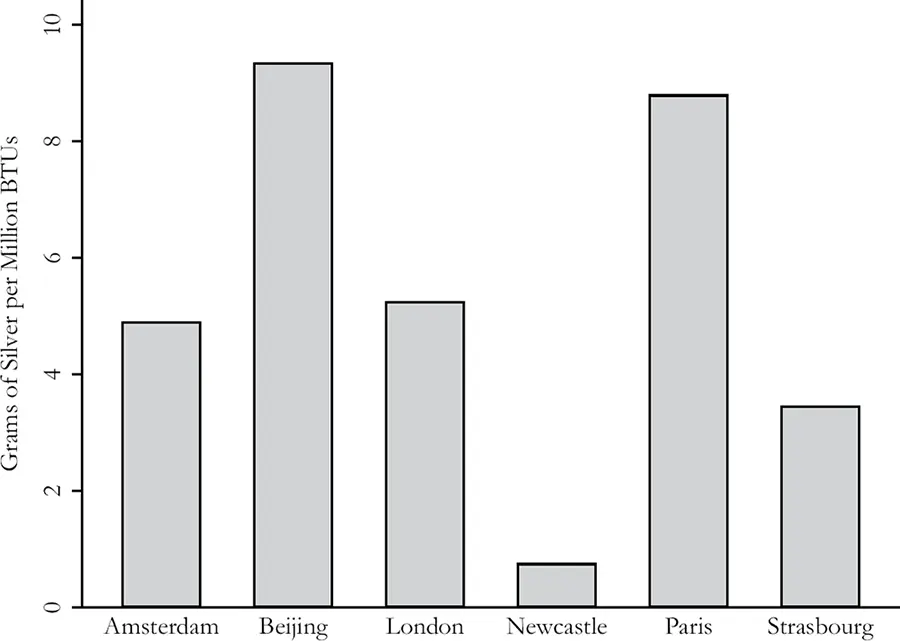

Perhaps the most direct impact of geography on economic growth is through the availability of natural resources. Nef (1932) demonstrated that 16th-century England faced an energy crisis as the charcoal supplied by local forests could not meet the demands of a growing urban population. Coal relaxed this constraint. Sure, English coal had been there long before the 16th and 17th centuries. But the demand for it was not. Once the steam engine was vastly improved in the late 18th century, cheap coal from the north of England (see Figure 2.10) allowed the British economy to harness vastly more energy than had previously been possible (Allen, 2009 a , 2011 b ).

Figure 2.10 The price of energy in the early 1700s

Data source : Allen (2011 b ). (BTUs = British Thermal Units.)

Building on this argument, Wrigley (1989, 2010) argues that without coal there would have been no Industrial Revolution. Specifically, he distinguishes between an organic economy (in which energy is extracted from human or animal muscle or from wood) from a mineral economy (in which energy stored up over millions of years becomes available for human use). Productivity is always bound to be low in an organic economy. Coal permitted Britain to escape from the constraints of an organic economy. Wrigley acknowledges that the presence of coal alone did not guarantee that it would be exploited. But without coal, industrialization would have been impossible.

In his now famous contribution to the Great Divergence debate, Pomeranz (2000) argued that British industrialization relied crucially on the proximity of coal deposits to the new industrial centers and on resources from the Americas. Traditional forms of energy such as timber were land-intensive. In comparison, coal yielded more power per unit of land. New crops from the Americas, notably the potato, increased the productivity of land in northwestern Europe. Natural resources shifted Britain and northwestern Europe from a labor-intensive path of economic development into an energy-intensive and innovative development path. For Pomeranz, access to the New World (and slavery)

offered what an expanding home market could not have: ways in which manufactured goods created without much use of British labour could be turned into ever-increasing amounts of land-intensive food and fiber (and later timber) at reasonable and even falling prices. Precious metals enabled Europeans to trade with Asia. Without silver it is difficult to imagine another European good being exported as much.

This argument has been challenged. After all, China had abundant coal deposits. So did the Ruhr Valley in Germany. The question of whether they were located close to industrial centers is perhaps the wrong one to ask. In Britain, industrial towns grew where coal was plentiful and energy cheap. It was also possible to transport coal cheaply by sea from Newcastle to fuel London’s demand for energy.

Mokyr (1990) argues that coal was unlikely to have been decisive, for a variety of reasons. First, the Industrial Revolution was broader than steam power, and even steam power did not absolutely require coal. Water power was an important substitute. Had coal been more expensive, innovators would have had an incentive to economize on it and develop alternative energy sources. The supply of coal was highly elastic (Clark and Jacks, 2007). This implies that coal production expanded as demand for coal increased with industrialization. By this account, the expansion of coal output could have occurred in earlier decades had there been demand. In other words, had Britain had no coal, this would not have prevented industrialization. Coal would simply have been imported from Ireland, France, or elsewhere in Northern Europe. This would have been costly, but the additional costs were unlikely to have been decisive for Britain’s industrialization. This speaks against Pomeranz’s claim that the supply of coal was a binding constraint for industrialization to take place.

One can hardly deny the power of geography in explaining many patterns in the pre-industrial world. Geographic characteristics were critical in the emergence of agricultural and urban life in the Fertile Crescent. Geographic features such as access to rivers and coasts and high-quality agricultural land also help explain many patterns of comparative development prior to industrialization.

But this does not mean that geography can provide a full answer for the puzzle of comparative economic development. Before 1800, better-endowed lands were not much richer in per capita terms than were less well-endowed lands. They just tended to be more densely populated. Moreover, while geographic characteristics can explain much of the variation in the location of economic activity, they do not provide the full story. Firms benefit from being near each other. So do workers. Economies of scale and the network effects associated with close proximity (known in economics as agglomeration effects), rather than geographic fundamentals, often explain why certain cities outperform others. Most importantly, geography on its own cannot account for the timing of the Industrial Revolution, the onset of modern, sustained economic growth in the 19th century, or the various reversals of fortune that we observe in the historical record.

Where does this leave us? Is there a role for geography in explaining why the world became rich? Hopefully, this chapter has convinced you that geography has played an important role in determining certain outcomes that differ between societies, but that it cannot explain everything. If it could explain everything, our fate would have been written thousands of years ago with little room for human agency. In the remaining chapters, we will show that human actions have played a significant role in determining the economic trajectories of societies. These decisions range from the most intimate (how many babies to have) to the type of legal and political systems societies have. Yet, even though human actions have played a key role in determining the world’s economic distribution, geography likely played some role in these decisions. To some degree, geography has helped shape societies’ institutions (the subject of Chapter 3), culture (the subject of Chapter 4), demography (the subject of Chapter 5), and colonization (the subject of Chapter 6). We will keep these interactions in mind as we proceed through the first half of the book.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.