10 3.10 A,B,C,EKCO is increased in restrictive defects caused by extrapulmonary factors.

4 Radiology of the chest

Chest X‐ray

The chest X‐ray has a key role in the investigation of respiratory disease. The standard view is the erect, postero‐anterior( PA) chest X‐raytaken at full inspiration with the X‐ray beam passing from back to front. A lateral X‐raygives a better view of lesions lying behind the heart or diaphragm, which may not be visible on a PA view, and allows abnormalities to be viewed in a further dimension. Supine and antero‐posterior (AP) viewsare usually taken at the bedside using mobile equipment in patients who are too ill to be brought to the X‐ray department. AP films are less satisfactory in defining many abnormalities, producing magnification of the cardiac outline, for example.

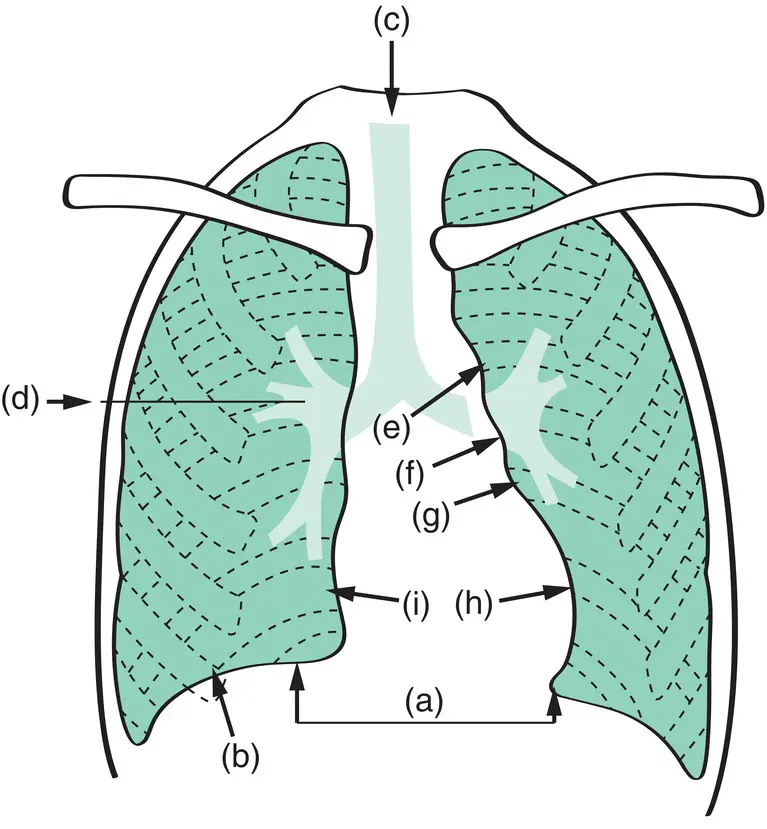

The main landmarks of the normal chest X‐ray are shown in Figs 4.1and 4.2. X‐rays should be examined both close up and from a short distance from the computer screen in an area with reduced background lighting. It is important to confirm the name and date on the X‐ray and to check the technical quality of the film. Symmetry between the medial end of both clavicles and the thoracic spine confirms that the film has been taken without any rotation artefact. If the film has been taken in full inspiration, the right hemidiaphragm is normally intersected by the anterior part of the sixth rib. The vertebral bodies are usually visible through the cardiac shadow if the X‐ray exposure is satisfactory.

It is helpful to examine the film systematically to avoid missing useful information. The shape and bony structures of the chest wall should be surveyed and the position of the hemidiaphragms and trachea noted. The shape and size of the heart and the appearances of the mediastinum and hilar shadows are examined. The size, shape and disposition of the vascular shadows are noted and the pattern of the lung markings in different zones is carefully compared. It is advisable to focus attention on areas of the chest X‐ray where lesions are commonly missed, such as the lung apices, hila and the area behind the heart. Any abnormality detected should be analysed in detail and interpreted in the context of all clinical information. It is often helpful to obtain previous X‐rays or to monitor the evolution of abnormalities over time on follow‐up X‐rays. Some of the radiological features of the major lung diseases are shown in individual chapters. In some circumstances chest X‐ray abnormalities follow a specific pattern that allows a differential diagnosis to be outlined.

Abnormal features

Collapse

Obstruction of a bronchus by a carcinoma, foreign body (e.g. inhaled peanut) or mucus plug causes loss of aeration with ‘ loss of volume’ and collapse of the lung distal to the obstruction. Collapse of each individual lobe of the lung produces its own particular appearance on chest X‐ray ( Figs 4.3and 4.4) with shift of landmarkssuch as the mediastinum resulting from loss of volume. Obstruction of a main bronchus usually causes obvious asymmetry ( Fig. 4.5). Compensatory expansionof other lobes may result in increased transradiency of adjacent areas of the lung.

Right upper lobecollapse is relatively easy to spot on a plain chest X‐ray; there is an area of increased density in the upper medial aspect of the right hemithorax with elevation of the horizontal fissure and right hilum. In right middle lobecollapse there may be little to see on a PA X‐ray apart from lack of definition of the right heart border. This is a useful sign that helps to distinguish it from right lower lobecollapse where the right border of the heart remains clearly defined. In right lower lobe collapse there is also a triangular opacity in the right lower zone (usually medially) pointing to the hilum and the medial aspect of the right hemidiaphragm is obscured. The left upper lobecollapse santeriorly, becoming a thin sheet of tissue up against the anterior chest wall. It appears like a veil, most obvious superiorly and fading inferiorly. Left lower lobecollapse is manifest as a triangular area of increased density behind the heart shadow, often with a shift of the heart shadow to the left and increased transradiency of the left hemithorax because of compensatory expansion of the left upper lobe (see Fig. 4.4). Collapse is a sinister sign often indicating an obstructing carcinoma that may be confirmed by bronchoscopy.

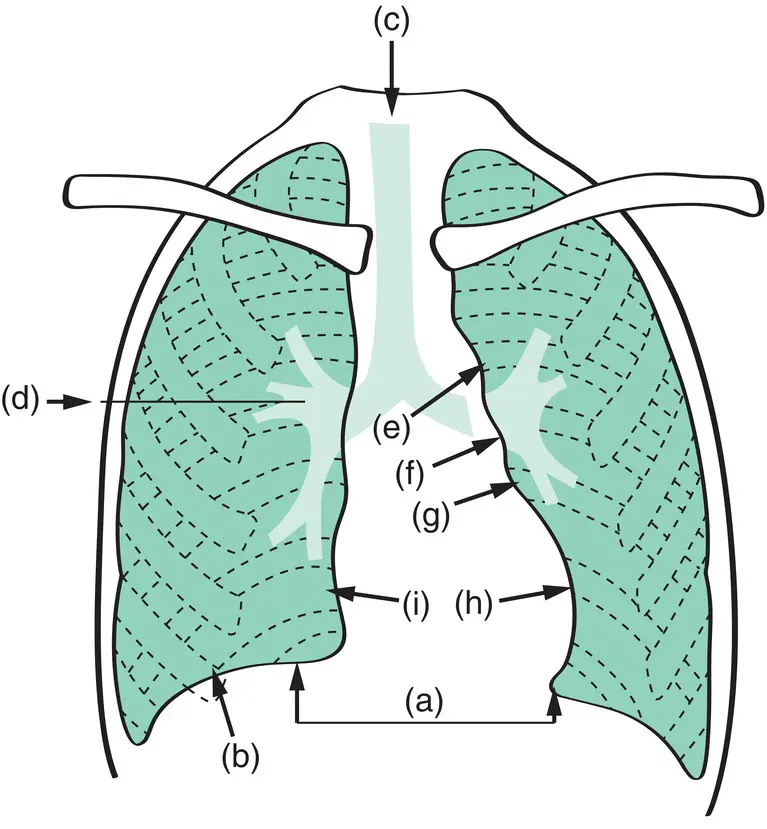

Figure 4.1 Diagram of chest X‐ray (PA view). The right hemidiaphragm is 1–3 cm higher than the left (a) and on full inspiration it is intersected by the shadow of the anterior part of the sixth rib (b). The trachea (c) is vertical and central or very slightly to the right. The horizontal fissure (d) is found in the position shown and should be truly horizontal. It is a very valuable marker of change in volume of any part of the right lung. The left border of the cardiac shadow comprises (e) aorta; (f) pulmonary artery; (g) concavity overlying the left atrial appendage; (h) left ventricle. The right border of the cardiac shadow (i) is formed by the right atrium, the superior vena cava entering superiorly and the inferior vena cava which is often seen at its lower margin.

Air in the lungs appears black on X‐ray. Consolidation appears as areas of opacificationsometimes conforming to the outline of a lobe or segment of lung in which the air has been replaced by an inflammatory exudate (e.g. pneumonia), fluid (e.g. pulmonary oedema), blood (e.g. pulmonary haemorrhage) or tumour (e.g. carcinoma with lepidic growth). Bronchi containing air passing through the consolidated lung are sometimes clearly visible as black tubes of air against the white background of the consolidated lung: air bronchograms(see Fig . 17.2). Structures such as the heart, mediastinum and diaphragm are usually clearly outlined as a silhouette on an X‐ray because of the contrast between the blackness of aerated lung and the whiteness of these structures. When there is abnormal shadowing in the lung adjacent to these structures, there is loss of the sharp outline, and this is often referred to as the silhouette sign although it is the absence of the expected silhouette that indicates an abnormality ( Fig. 4.6).

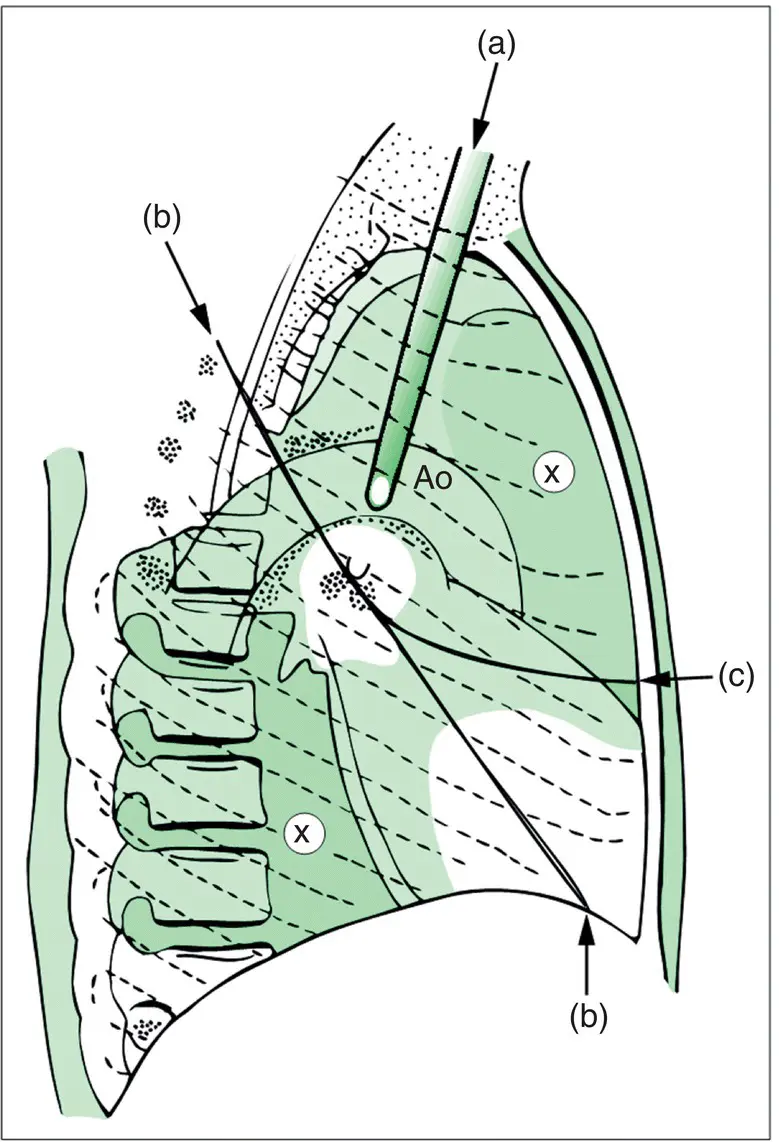

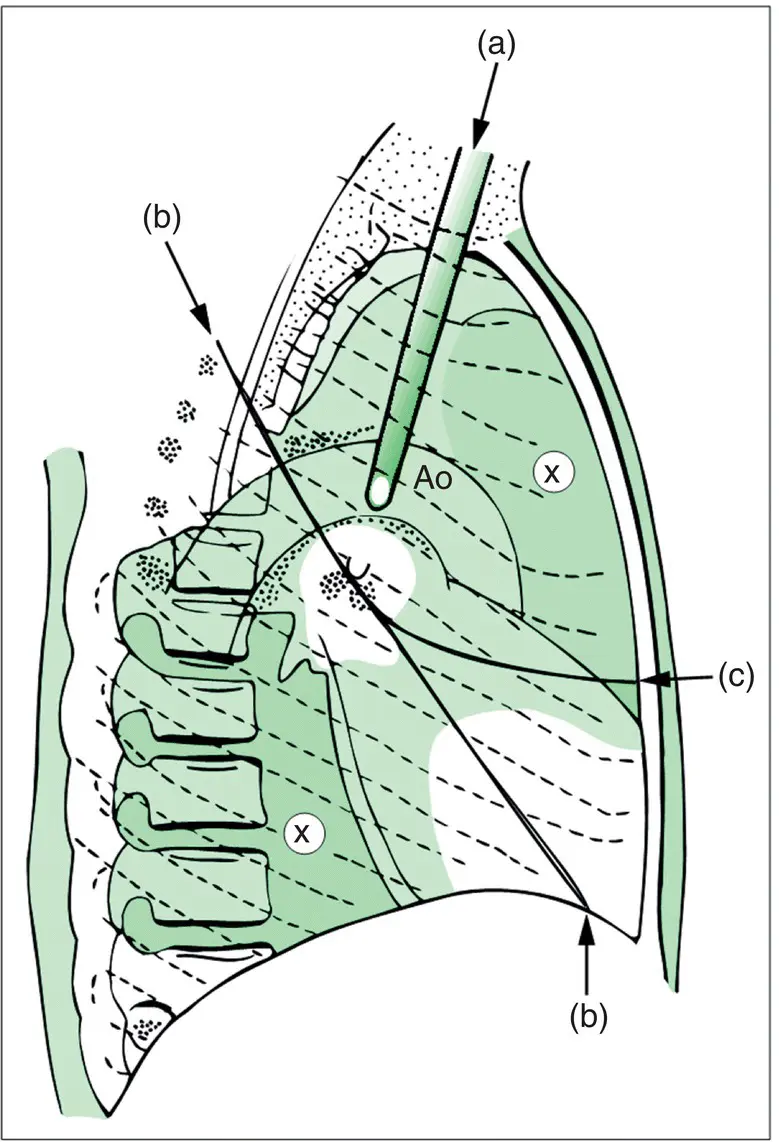

Figure 4.2 Diagram of chest X‐ray (lateral view). (a) Trachea. (b) Oblique fissure. (c) Horizontal fissure. It is useful to note that in a normal lateral view, the radiodensity of the lung field above and in front of the cardiac shadow is about the same as that below and behind (x). Ao, aorta.

Various descriptive terms such as ‘rounded opacity’, ‘nodule’ or ‘coin lesion’ are used to refer to pulmonary masses. Carcinoma of the lung is the most important cause of a mass on chest X‐ray but several other diseases may cause a similar appearance ( Table 4.1, Fig. 4.7). Features such as cavitation, calcification, rate of growth, the presence of associated abnormalities(e.g. lymph node enlargement) and whether the lesion is solitaryor whether multiplelesions are present may provide clues to diagnosis. However, these features are often not reliable indicators of aetiology, and the X‐ray appearances must be interpreted in the context of all the clinical information. Further investigations such as computed tomography (CT) and biopsy (bronchoscopic, percutaneous, surgical) are often necessary.

Читать дальше