A lot of methane is frozen into the ground of the Arctic, trapped by the permafrost (any ground that remains completely frozen for more than two years). Rising northern temperatures, however, are melting the soil. When the Arctic land thaws, it becomes swampland — and it starts dishing out methane like hotcakes. We look at this problem in greater detail in Chapter 7.

A lot of methane is frozen into the ground of the Arctic, trapped by the permafrost (any ground that remains completely frozen for more than two years). Rising northern temperatures, however, are melting the soil. When the Arctic land thaws, it becomes swampland — and it starts dishing out methane like hotcakes. We look at this problem in greater detail in Chapter 7.

The amount of nitrous oxide (N 2O) in the atmosphere is even smaller than the amount of methane, but it accounts for about 7 percent of the overall greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect of nitrous oxide per unit is almost 300 times more potent than that of carbon dioxide. This gas is actually still going up at a rate of 1 part per billion (ppb) each year — as of 2018, it was at 331 parts per billion. Increasingly, nitrous oxide comes from human activities.

The following are ways nitrous oxide appear in the atmosphere:

In agriculture, farmers encourage those natural bacteria to produce more of the gas through soil cultivation and the use of natural and artificial nitrogen fertilizers. The biggest source of nitrous oxide, natural or human-made, is fertilizers used in agriculture. Fertilizers count for 60 percent of human-made sources and 40 percent of sources overall.

Ocean- and soil-dwelling bacteria produce nitrous oxide naturally as a waste product.

Dentists use nitrous oxide as an anesthetic. (Laughing gas is nitrous oxide — not so funny now, is it? Though it’s in such small amounts that you don’t need to worry about your root canal adding to global warming.) Industrial processes (to create nylon, for example) also produce nitrous oxide.

Humans add a lot of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere by using automobiles. Ironically, cars produce the gas as a side result of solving another environmental problem — see the nearby sidebar for the scoop.

Hydrofluorocarbons. Perfluorocarbons. Sulfur hexafluoride. Try saying those names three times fast. They’re as hard to say as they are effective at trapping heat. These three types of gases are all human-made and don’t exist naturally in the atmosphere. They come from a number of different industrial processes that create air pollution.

Almost all car air-conditioning systems use the 13 hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). (We look at how industry emits these GHGs in detail in Chapter 5.) Most of the seven perfluorocarbons (PFCs) are by-products of the aluminum industry. Sulfur hexafluoride (SF 6) comes from producing magnesium, and many types of industry use it in insulating major electrical equipment.

HOW GOOD INTENTIONS INCREASED NITROUS OXIDE EMISSIONS

Fossil fuels (which we discuss in greater detail in Chapter 4) contain nitrogen. When cars burn gasoline, they give off the nitrogen-based chemicals nitrogen monoxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO 2) — together known as NO xgases. These NO xgases create acid rain and smog in cities.

In response to these environmental problems, governments in North America forced car companies to put catalytic converters in all their cars. Catalytic converters convert smog-causing chemicals into other chemicals that aren’t as damaging to our lungs and don’t cause acid rain.

Unfortunately, these catalytic converters turn NO xgases, which don’t have an effect on climate change, into nitrous oxide (N 2O), which does! (One more reason, if you need it, why everyone should drive less.)

Other players on the GHG bench

The two GHGs that we talk about in the following sections do play a role in climate change, but they aren’t on the United Nations list of 24 GHGs and get left aside in most discussions about the impact of GHGs on global warming — not for scientific reasons, but because of decisions made in international negotiations.

As we discuss in the section, “ Focusing On Carbon Dioxide: Leader of the Pack,” earlier in this chapter, water vapor is a huge player in the greenhouse effect. As shocking as it may seem, good ol’ H 2O (two parts hydrogen, one part water) causes the majority — 60 percent — of the planet’s greenhouse effect. But the ramped-up threat of climate change isn’t tied to water vapor. Water vapor remains an essential reason the planet is warm enough to sustain current life forms.

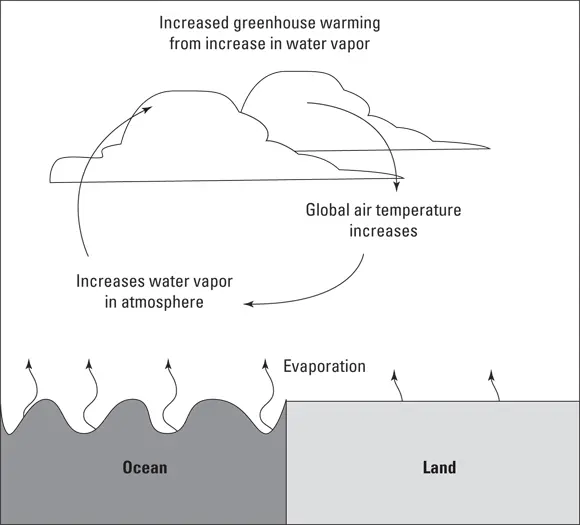

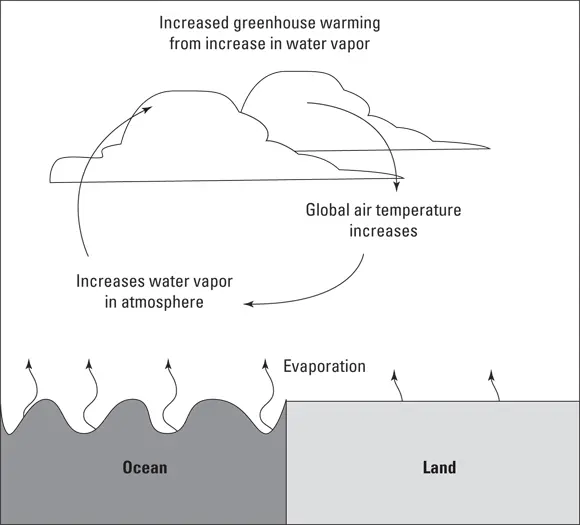

Unlike the production of the other GHGs, humans don’t directly cause the increase of water vapor. But the other gases that are produced heat up the atmosphere. When plants, soil, and water warm up, more water evaporates from their surfaces and ends up in the atmosphere as water vapor. A warmer atmosphere can absorb more moisture. The atmosphere will continue to absorb more moisture while temperatures continue to rise. See Figure 2-6.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-6:Water evaporates and lingers in the atmosphere.

Water vapor also differs greatly from other GHGs because the atmosphere can hold only so much of it. When you watch a weather forecast, you hear the term relative humidity, which refers to the amount of water vapor currently in the atmosphere compared to how much the atmosphere can hold. On a really hot and sticky day, the relative humidity may be 90 percent — the atmosphere has just about taken in all the water vapor it can. When the relative humidity reaches 100 percent, clouds form, and then precipitation falls, releasing the water from the air.

Water vapor also differs greatly from other GHGs because the atmosphere can hold only so much of it. When you watch a weather forecast, you hear the term relative humidity, which refers to the amount of water vapor currently in the atmosphere compared to how much the atmosphere can hold. On a really hot and sticky day, the relative humidity may be 90 percent — the atmosphere has just about taken in all the water vapor it can. When the relative humidity reaches 100 percent, clouds form, and then precipitation falls, releasing the water from the air.

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are also considered GHG, responsible for about 12 percent of the greenhouse effect the planet is experiencing today. You don’t find much of these CFC gases around anymore because the Montreal Protocol of 1989 required countries to discontinue their use. CFCs break down the ozone — the layer throughout the stratosphere that intercepts the sun’s most deadly rays. (Without the ozone layer, the sun’s ultraviolet rays would kill all living things.) CFCs were mostly used in aerosol spray cans and the cooling liquids in fridges and air conditioning. The Montreal Protocol was a fantastic success. The use of chemicals that destroy the ozone layer is illegal — globally. And now the ozone layer has started repairing itself! A side effect of banning ozone-eating chemicals is that a lot of them were also GHGs. So protecting the ozone layer also helped the climate!

Because CFCs are already regulated under the Montreal Protocol, they’re not regulated under climate agreements. The recent Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol will remove a significant amount of GHG that are also ozone depleters (Read more about what gases are covered under the Kyoto Protocol in Chapter 11.)

Because CFCs are already regulated under the Montreal Protocol, they’re not regulated under climate agreements. The recent Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol will remove a significant amount of GHG that are also ozone depleters (Read more about what gases are covered under the Kyoto Protocol in Chapter 11.)

RUNNING UP EMISSIONS WITH YOUR SNEAKERS

Some of the sources of these gases are really wild. Here’s one: Nike came out with the popular Nike Air shoe, a running shoe with a cool little air-filled bubble in the heel, in the late 1980s. That bubble was filled with — you guessed it — a GHG (Sulfur hexafluoride, to be exact)!

The amount of GHG in those shoes all together added an equivalent of about 7 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — or the emissions from 1 million cars — into the air when they hit the garbage dump after being worn out. In the summer of 2006, after 14 years of research and pressure from environmental groups, Nike stopped using the GHG in shoes and replaced it with nitrogen. We’re glad that bubble burst.

Читать дальше

A lot of methane is frozen into the ground of the Arctic, trapped by the permafrost (any ground that remains completely frozen for more than two years). Rising northern temperatures, however, are melting the soil. When the Arctic land thaws, it becomes swampland — and it starts dishing out methane like hotcakes. We look at this problem in greater detail in Chapter 7.

A lot of methane is frozen into the ground of the Arctic, trapped by the permafrost (any ground that remains completely frozen for more than two years). Rising northern temperatures, however, are melting the soil. When the Arctic land thaws, it becomes swampland — and it starts dishing out methane like hotcakes. We look at this problem in greater detail in Chapter 7.

Water vapor also differs greatly from other GHGs because the atmosphere can hold only so much of it. When you watch a weather forecast, you hear the term relative humidity, which refers to the amount of water vapor currently in the atmosphere compared to how much the atmosphere can hold. On a really hot and sticky day, the relative humidity may be 90 percent — the atmosphere has just about taken in all the water vapor it can. When the relative humidity reaches 100 percent, clouds form, and then precipitation falls, releasing the water from the air.

Water vapor also differs greatly from other GHGs because the atmosphere can hold only so much of it. When you watch a weather forecast, you hear the term relative humidity, which refers to the amount of water vapor currently in the atmosphere compared to how much the atmosphere can hold. On a really hot and sticky day, the relative humidity may be 90 percent — the atmosphere has just about taken in all the water vapor it can. When the relative humidity reaches 100 percent, clouds form, and then precipitation falls, releasing the water from the air.