2.2.4.2 Fluorescent Probes for Biological Sensing

Fluorescent biosensor has been widely concerned because of its high sensitivity and simple operation. AIE molecules are widely used in bioassays due to their unique “turn‐on” luminescence properties. Tian and coworkers used the water‐soluble probe molecule 4‐5to detect endonuclease S1 [94]. The aqueous solution of the AIE fluorescent probe 4‐5has no fluorescence. When ssDNA is added, the negatively charged ssDNA and the positively charged probe molecule are combined by electrostatic interaction and hydrophobic interaction. Then, the probe molecules aggregate, enhancing the fluorescence of the solution. When the S1 enzyme is added, ssDNA is cleaved into fragments. The large number of probe molecules are dispersed in the solution, and the fluorescence of the solution is weakened. The specific detection of the S1 enzyme can be realized by observing the fluorescence change of the solution. In addition, the activity of the S1 enzyme can be regulated by the inhibitor. Based on this method, the S1 enzyme inhibitor can also be screened out.

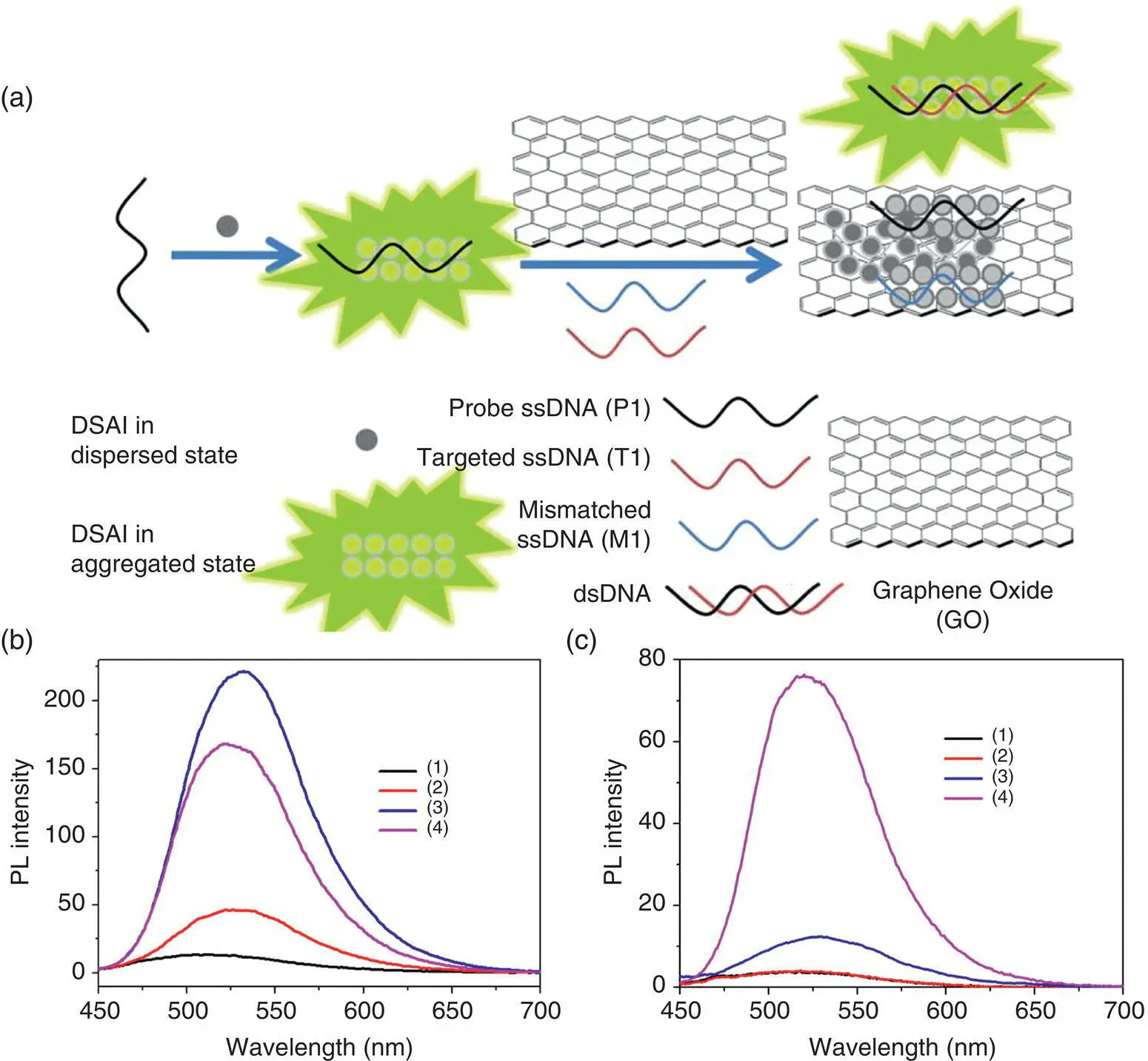

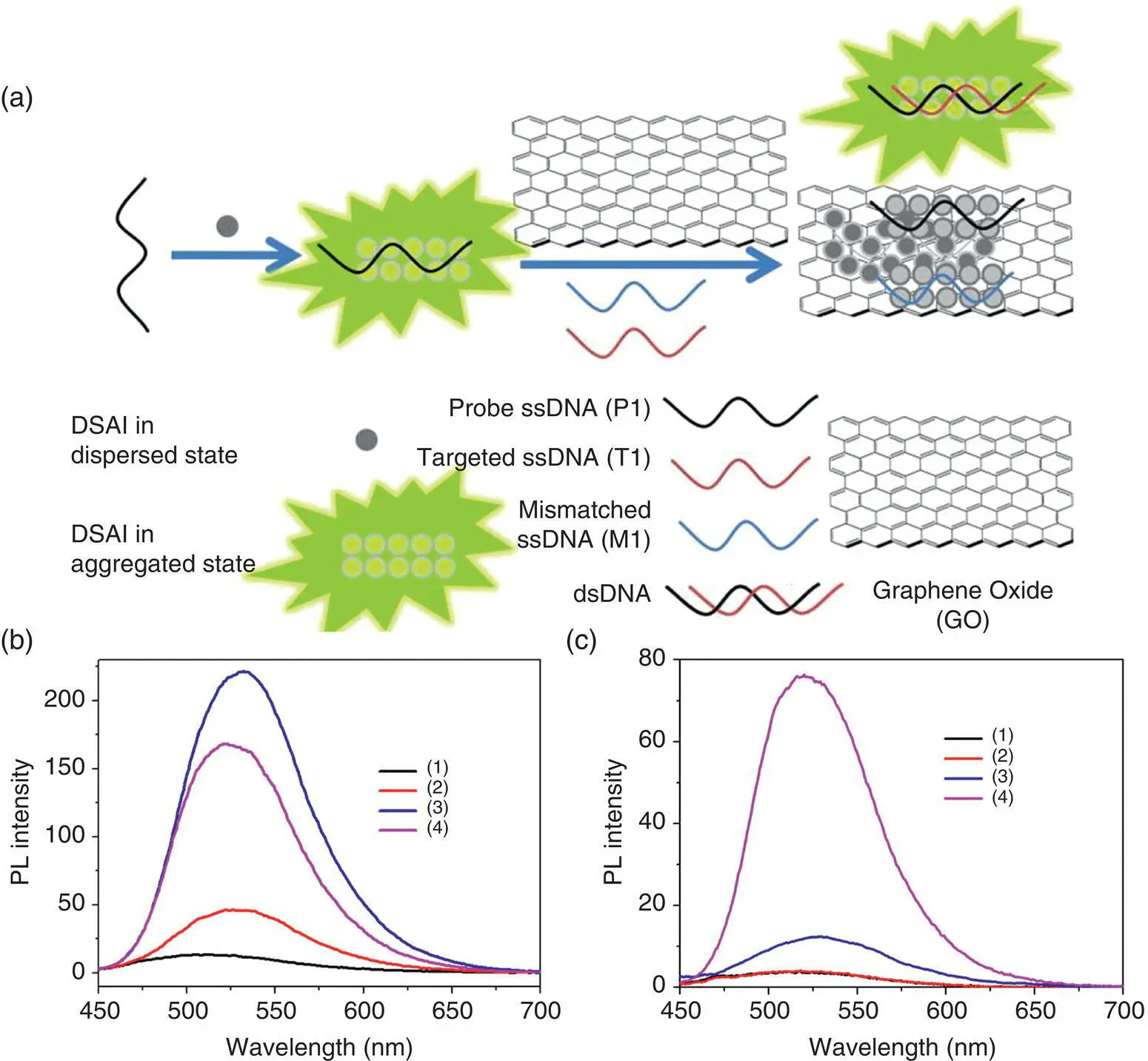

In the recent years, carbon nanomaterials such as GO and water‐soluble carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have become a hot research topic in the field of biosensing due to their excellent physicochemical properties and strong quenching ability of luminescent molecules. Investigation results have indicated that GO can selectively adsorb ssDNA. However, as to double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA) with a double helix structure or ssDNA with high folding degree, GO has weak adsorption ability. Based on this, Tian's research team used the probe molecule 3‐5(i.e. DSAI in Figure 2.13) and GO to achieve “turn‐on” recognition of target DNA (T1) (see Figure 2.13a) [89]. The probe molecule 3‐5is weakly fluorescent in aqueous solution (see Figure 2.13b, c, curve 1). After the addition of unlabeled ssDNA (P1), P1 and probe molecule 3‐5aggregate to form a complex, 3‐5/ssDNA aptamer complex, and the fluorescent emission is enhanced (see Figure 2.13b, c, curve 2). Under the condition without GO, the fluorescent intensity of the interferential mismatched ssDNA (M1) (see Figure 2.13b, curve 3) is a little stronger than that of the targeted complementary ssDNA (T1) (see Figure 2.13b, curve 4), indicating that the AIE‐active aptasensor could not distinguish T1 from M1. When GO is introduced, the fluorescence of the solution is quenched due to the adsorption of 3‐5/ssDNA aptamer complex onto GO. When M1 is added, there is no obvious fluorescent enhancement. However, with the addition of T1, P1 binds to T1 to form dsDNA, thereby breaking the binding of GO. At the same time, probe 3‐5and dsDNA form a new complex and the new complex stays away from GO; thus, the fluorescence of the solution is gradually enhanced, which realizes the “turn‐on” recognition of the target DNA.

To further understand the sensing mechanism of the system and optimize the sensing performance, Tian's group studied the interaction of AIE probe, DNA, and GO, which realized the construction of a highly sensitive and highly selective DNA sensing platform [95]. It is found that the probe molecules are tightly bound to dsDNA by intercalation and are not easily adsorbed by GO. Changing the sequence of dsDNA and mutating one of the bases will destroy the double helical chain. It weakens the binding of the probe molecule to the site of the mutation, and the probe molecule is easily adsorbed by the GO, which weakens the fluorescence of the solution. Based on the same mechanism, they used the probe molecule 3‐5and CNTs to detect single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) defined as the mutation of a single base pair in the genome, which is the most general form in genetic variation and can induce a few human genetic diseases and protein dysfunctions [96].

Figure 2.13 (a) Schematic description of the selective fluorescent aptasensor based on the probe molecule 3‐5(i.e. DSAI in the figure)/GO probe; fluorescence emission spectra of 3‐5in the absence (b) and presence (c) of GO at different conditions: (1) 3‐5in buffer; (2) 3‐5+ P1 (200 nM); (3) 3‐5+ P1 + M1 (200 nM); and (4) 3‐5+ P1 + T1 (200 nM) [89].

Source : Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref. [89]. Copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society.

Like the detection of DNA by cationic probes, anionic AIE probes can also be used to detect proteins by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Tian's research team designed and synthesized a water‐soluble sulfonate 4‐6based on DSA [97]. In the solution, the probe molecule 4‐6exhibits a weak fluorescence. When bovine serum albumin (BSA) is added, the probe molecule enters the hydrophobic cavity of the BSA folded chain and aggregates, and then the fluorescence of the solution is illuminated. Thereby, the purpose of detecting BSA is successfully achieved. In addition, the probe molecule 4‐5can also detect the changes in the BSA folded structure [92]. When cetyltrimethylammonium bromide is added, the hydrophobic cavity of the BSA folded structure is destroyed, resulting in the inability of the probe molecules aggregating. The fluorescence of the solution becomes weak.

Ouyang's research team used 4‐6as a fluorescent probe to realize the real‐time monitoring of the unfolding process of erythropoietin (EPO) [98]. In the solution, the probe molecules hardly emit fluorescence. When EPO is added, the probe molecules combine with the hydrophobic cavity of EPO and accumulate, and the fluorescence of the solution is illuminated. The detection limit is up to 1 nM. When guanidine hydrochloride (GndHCl) (the protein denaturant) is added, EPO changes from the original folded structure to a random coil structure. In this process, the binding of the probe molecule to EPO is weakened, and resultantly, the fluorescence of the solution is annihilated.

In addition to DNA and proteinaceous biomacromolecules, many small biomolecules such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) also play a significant role in the complicated biological systems. A label‐free and turn‐on fluorescent aptasensor for ATP detection was reported with a ssDNA‐1 aptamer selected as the recognition part, an AIE molecule 3‐5as the fluorescent probe, and water‐soluble CNTs as the fluorescent quencher [99]. First, the probe molecule binds to DNA‐1 and the solution emits a weak fluorescence. When the CNTs were added, the fluorescence of the solution was quenched. However, after ATP was added, ATP and DNA‐1 formed a new complex, which left the surface of CNTs. In this case, the probe molecules were still adsorbed on the surface of the complex, and the fluorescence of the solution was illuminated. However, when the other adenosines were added, they did not specifically bind to DNA‐1. DNA‐1 and probe molecules were still entangled in CNTs, resulting in no fluorescence in the solution. Therefore, high sensitivity and specific detection of ATP could be achieved by observing the change in the fluorescence intensity of the probe molecule.

2.3 Conclusions and Outlook

This chapter mainly introduces the research progress of the AIE properties and applications of AIE small molecules and macromolecules based on DSA. These AIE materials have weak or no luminescence in the solution, but in the aggregation state or solid state, their fluorescence increases significantly because the intramolecular vibrational motion annihilates the excitons in the solution state. While in the aggregation state, the distorted molecular configuration results in abundant intermolecular interaction, which limits the vibrational motion within the molecules, so that the molecules can effectively luminesce. On the other hand, the specific molecular packing also plays important roles in achieving enhanced fluorescence emission for these AIE molecules in the aggregation state. Due to the excellent luminescent properties of these AIE materials in aggregate or solid state, they have exhibited wide application prospects in the fields of response luminescence upon external stimulus, high solid luminescence organic materials, fluorescent bioimaging, fluorescent probes for chemical and biological sensing, and so on. The research on DSA and its derivatives enriches the AIE material system, broadens the application fields of AIE materials, and deepens the understanding of the mechanism of AIE luminescence. In the future work, we will combine the luminescent properties of AIEgens and self‐assembly together to develop self‐assembly‐based novel supramolecular luminescent systems with high efficiency. Through designing and synthesizing new AIE molecules and developing the novel methods and techniques of supramolecular assembly, we can realize the highly efficient luminescent ordered assembly with different size and morphology and investigate the relationship between the material structure and the luminescent properties, revealing the intrinsic photophysical mechanism of the ordered assembly. Subsequently, we will explore the applications of the supramolecular luminescent system based on AIEgens and self‐assembly in chemistry, material electronics, life science, and other important fields. These investigations will definitely provide a theoretical basis and practical evidence for the design and synthesis of new efficient luminescent materials and lay the foundations for expanding the function and application of AIE materials.

Читать дальше