Unifying gravity with the other forces would create a new version of the Standard Model and would explain how gravity works on the quantum level. Many physicists hope that string theory will ultimately prove to be this theory.

Einstein’s failed quest to explain everything

After Einstein successfully worked the major kinks out of his theory of general relativity, he turned his attention toward trying to unify this theory of gravity with electromagnetism as well as with quantum physics. In fact, he would spend most of the rest of his life trying to develop this unified theory but would die unsuccessful.

Throughout this quest, Einstein looked at almost any theory he could think of. One of these ideas was to add an extra space dimension and roll it up into a very small size. This approach, called Kaluza-Klein theory after the men who proposed it, is addressed in Chapter 6. This same approach would eventually be used by string theorists to deal with the pesky extra dimensions that arose in their own theories.

Ultimately, none of Einstein’s attempts bore fruit. To the day of his death, he worked feverishly on completing his unified field theory in a manner that many physicists consider a sad end to such a great career.

Today, however, some of the most intense theoretical physics work is in the search for a theory to unify gravity and the rest of physics, mainly in the form of string theory.

A particle of gravity: The graviton

The Standard Model of particle physics explains electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force as fields that follow the rules of gauge theory. Gauge theory is based heavily on mathematical symmetries. Because these forces are quantum theories, the gauge fields come in discrete units ( quantum means “how much” in Latin) — and these units actually turn out to be particles in their own right, called gauge bosons. The forces described by a gauge theory are carried, or mediated, by these gauge bosons.

For example, the electromagnetic force is mediated by the photon. When gravity is written in the form of a gauge theory, the gauge boson for gravity is called the graviton. (If you’re confused about gauge theories, don’t worry too much — just remember that the graviton is what makes gravity work and you’ll know everything you need to know to understand their application to string theory.)

Physicists have identified some features of the theoretical graviton so that, if it exists, it can be recognized. For one thing, the particle is massless, which means it has no rest mass — a graviton is always in motion, and that probably means it travels at the speed of light (although in Chapter 20you find out about a theory of modified gravity in which gravity and light move through space at different speeds).

Another feature of the graviton is that it has a spin of 2. ( Spin is a quantum number indicating an inherent property of a particle that acts kind of like angular momentum. Fundamental particles have an inherent spin, meaning they interact with other particles like they’re spinning even when they aren’t.)

A graviton also has no electrical charge. It’s a stable particle, which means it won’t decay.

So physicists are looking for a massless particle moving at an incredibly fast speed, with no electrical charge and a quantum spin of 2. Even though the graviton has never been discovered by experiment, it’s the gauge boson that mediates the gravitational force. Given the extremely weak strength of gravity in relation to other forces, trying to identify a single graviton is an incredibly hard task. (It is, however, possible to identify the gravitational waves created by many gravitons, which was done very recently, as you find out in Chapter 6.)

So physicists are looking for a massless particle moving at an incredibly fast speed, with no electrical charge and a quantum spin of 2. Even though the graviton has never been discovered by experiment, it’s the gauge boson that mediates the gravitational force. Given the extremely weak strength of gravity in relation to other forces, trying to identify a single graviton is an incredibly hard task. (It is, however, possible to identify the gravitational waves created by many gravitons, which was done very recently, as you find out in Chapter 6.)

The possible existence of the graviton in string theory is one of the major motivations for looking toward the theory as a likely solution to the problem of quantum gravity.

Supersymmetry’s role in quantum gravity

Supersymmetry is a principle that says that two types of fundamental particles, bosons and fermions, are connected to each other. The benefit of this type of symmetry is that the mathematical relationships in gauge theory reduce in such a way that unifying all the forces becomes more feasible. (We explain bosons and fermions in greater detail in Chapter 8, while we present a more detailed discussion of supersymmetry in Chapter 10.)

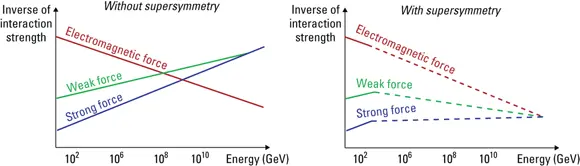

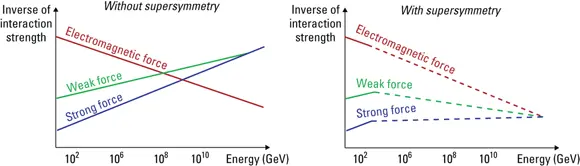

The top graph in Figure 2-2 shows the strengths of the three forces described by the Standard Model modeled at different energy levels. If the three forces met up in the same point, it would indicate that there might be an energy level where these three forces become fully unified into one single force.

Lisa Randall, 2005. Reproduced by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

FIGURE 2-2:If supersymmetry is added, the strengths of the forces in the Standard Model scale differently with energy, and they may become equal at high enough energy.

However, as the lower graph of Figure 2-2 shows, when supersymmetry is introduced into the equation (literally, not just metaphorically), the three forces meet in a single point. If supersymmetry proves to be true, it’s strong evidence that the three forces of the Standard Model unify at high enough energy.

Many physicists believe that all four forces are a manifestation of the same fundamental laws, which in string theory would be the dynamics of quantum strings. This should be apparent at high energy levels, but as the universe reduced into a lower-energy state, the inherent symmetry between the forces began to break down. This broken symmetry caused the creation of four apparently very different forces of nature.

The goal of a theory of quantum gravity is, in a sense, an attempt to look back in time, to when these four forces were unified into a single structure. If successful, it would profoundly affect our understanding of the first few moments of the universe — the last time the forces joined together in this way.

Chapter 3

Accomplishments and Failures of String Theory

IN THIS CHAPTER

Embracing string theory’s achievements

Embracing string theory’s achievements

Poking holes in string theory

Poking holes in string theory

Wondering what the future of string theory holds

Wondering what the future of string theory holds

String theory is a work in progress, having captured the hearts and minds of much of the theoretical physics community while being apparently disconnected from any realistic chance of definitive experimental proof. Despite this, it has had some successes — unexpected predictions and achievements that may well indicate string theorists are on the right track.

String theory critics would also point out (and many string theorists would probably agree) that the last couple of decades haven’t been kind to string theory because the momentum toward a unified theory of everything has slowed, and the latest particle colliders have failed to provide any direct evidence for string theory.

Читать дальше

So physicists are looking for a massless particle moving at an incredibly fast speed, with no electrical charge and a quantum spin of 2. Even though the graviton has never been discovered by experiment, it’s the gauge boson that mediates the gravitational force. Given the extremely weak strength of gravity in relation to other forces, trying to identify a single graviton is an incredibly hard task. (It is, however, possible to identify the gravitational waves created by many gravitons, which was done very recently, as you find out in Chapter 6.)

So physicists are looking for a massless particle moving at an incredibly fast speed, with no electrical charge and a quantum spin of 2. Even though the graviton has never been discovered by experiment, it’s the gauge boson that mediates the gravitational force. Given the extremely weak strength of gravity in relation to other forces, trying to identify a single graviton is an incredibly hard task. (It is, however, possible to identify the gravitational waves created by many gravitons, which was done very recently, as you find out in Chapter 6.)

Embracing string theory’s achievements

Embracing string theory’s achievements