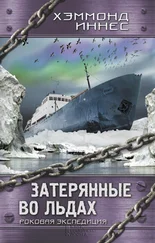

They got to within twenty feet or so of the ledge and there they paused, facing a gap full of powdered ice in which the sea sometimes showed. Vaksdal coiled his rope and leaped. For a moment I thought he’d made it. But the ice received his weight like a bog. In an instant he was up to his knees. Then he was floundering full length, with only the upper half of his body visible. He was within two yards of the ledge, but it might have been two miles for all the chance he had of reaching it.

Bland hesitated, staring at Vaksdal and coiling his rope. Then he backed away and started to run. Judie’s fingers dug into my arm. Whatever she might think of him now, Erik Bland was, after all, a part of her life. Instead of jumping, he flung himself full length in a beautiful tackle. His impetus carried him half across the gap, his body sliding on the surface of the ice, his arms working like a swimmer doing the crawl.

Then at last he was standing on the ledge itself and was hauling Vaksdal up after him. The men cheered wildly as the two men stood together on the ledge. Bland looked across at the cheering men. My eyes, weakened by the constant glare of the past few days, couldn’t make out the expression of his face.

But Howe was screaming in my ear, “He’s laughing at us! He’s on his own now! That’s what he wanted!”

I brushed him aside, shouting to Dahle, first mate of Hval V, whom I’d put in charge of loading, to get tools and anchors across. The men tied them to the rope, and as they were hauled across the two-hundred-yard gap, Howe was pulling at my sleeve and yelling, “He’ll abandon us, I tell you!”

“Don’t be a fool!” I snapped. “He can’t do anything without boats and stores!”

“Well, get yourself across with the first batch of men.”

I shook my head angrily. Now that Bland had done the job of getting the ropes across, as leader I was bound to be the last man to leave the camp.

Vaksdal and Bland were working like mad to fix the anchors firmly. As soon as this was done and the rope set up, the first boat was run across. About the middle the boat was bumping dangerously on the ice, and just before it reached the ledge one of the two anchors broke out. Fortunately, the other anchor held and the boat was got safely to the ledge. But this made me realize that more men were required on the ledge at once. As the slings were hauled back I gave the order for the first batch of men to go, instead of stores, which were next on the loading table.

Gerda came across to me as the men were getting into the slings. “I think you should be there, Duncan!” she shouted. “It is important nothing go wrong at that end!”

I didn’t like the idea of being one of the first across, but I had already decided that I should be there. I ordered Dahle to assume command of the rear party and took the place of one of the men in the slings. We also hitched on the two remaining anchors.

With the extra personnel and anchors, we soon had both lines set up securely and began to ferry the stores across.

It was while we were hauling the second boat across that the movement of the old camp on the floe in relation to the iceberg first became really noticeable. What had happened was that the floe berg had been caught in a sort of eddying outthrust of ice and was moving outward, away from the berg.

At length we were hauling in the last boat. As it came in to the ledge somebody shouted to me. A rope end went trailing over the edge. I glanced quickly across at the huddle of dark figures on the ice. They were standing, staring toward us, quite motionless. All the stores had been cleared. There was just the rear guard — Dahle and five of the Hval V crew. The floe on which they stood was being whirled away from us, caught in a gigantic surge of the ice. We flung our weight on the last remaining rope. But it was dragged from our hands by forces far beyond our puny strength. The end of it trailed over on to the ice and we could do nothing but stand and watch that little group of figures alone in a heaving chaos.

I put my arm round Jodie’s shoulders. She was tense, her face white and her lips moving in agitated prayer. The floe berg on which Dahle and his companions were marooned was turning slowly round and round, as though it were at the very center of a revolving whirlpool. A moment later it split. Two of the men abandoned their shattered ice island and began floundering toward us across the churning ice. They were right in broken ice now. They hadn’t a chance.

Through my glasses I could see only three men standing near where our camp had been. One was Dahle. The remains of the floe berg began to roll. The three men scrambled and clawed their way across the ice, fighting to keep on the uppermost side.

It was horrible, standing there watching them go like that, especially as I should have been one of them. Judie must have understood my mood, for her hand gripped my arm. “It’s not your fault,” she said.

“If we’d been quicker,” I answered. “If we’d started on the job a few minutes earlier.” I turned away angrily. No good brooding over it. There was work to be done.

I detailed a dozen men to cut a way through the jagged ice of the ledge and drag the boats up as far as possible. Then I turned to get the stores secured and the tents pitched. And as I turned. Bland came toward me. As he approached, he seemed to have an air of truculence, and there was something about his eyes, a queer sort of confidence, something like a sneer. He had lost the dazed look.

He came right over and stopped in front of me. “I want a word with you, Craig,” he said. There was a sudden authority in his tone, and I saw several of the men stop work to watch us.

“Well?” I asked.

“In the future you’ll keep away from my wife,” he said.

“That’s for her to decide,” I answered.

“It’s an order,” he said.

I stared at him. “The hell it is!” I said. “Get to work on the boats, Bland.”

He shook his head, grinning. “You don’t give orders here.” And then, in a moment of quiet, he said, “Mr. Craig, please understand that, now that Larvik is dead, I am in command.” He swung round on the men, who were all watching us now. “In the absence of my father, I shall, of course, take command here as his deputy. As commander I brought the ropes across. Craig, as second in command, should have remained with the rear party as I instructed, but—” He shrugged his shoulders... “As a newcomer to the company,” he said to me, “you will realize that you are too inexperienced to have any sort of command in a situation like this.” He turned abruptly and strode toward the men. There was almost a swagger in the way he walked.

I just stood there, too amazed to make a move. I remember thinking, Howe was right. He’s got back his confidence, Nordahl’s death, the ramming — he’s forgotten it all. And I cursed myself for not realizing he was dangerous.

He began shouting orders at the men. I saw the amazement I felt written on their faces. Hut they were overawed by the terror of their surroundings. They would follow any leader, so long as he led. I started forward, and as I came up to Bland I heard him announce the reinstatement of Vaksdal and Keller as mates. He gave an order. The men hesitated. Their eyes shifted to me. Bland turned. The sneer was gone now, but the truculence was still there. I ordered him to pick up one of the packing cases. His eyes shifted quickly from me to the men. And as he didn’t move when I repeated the order, I knew there was only one thing to do. “McPhee. Kalstad.” The two Hval IV men moved forward. “Arrest that man,” I ordered. And then, turning quickly to Bland, I said, “Erik Bland, you are charged with the murder of Bernt Nordahl and also with the deliberate ramming of Hval Four, an action which caused the immediate death of two men and which may be responsible for all our deaths. You will lie held for trial when and if we ever reach civilization.”

Читать дальше