Hammond Innes

Calling the Southern Cross!

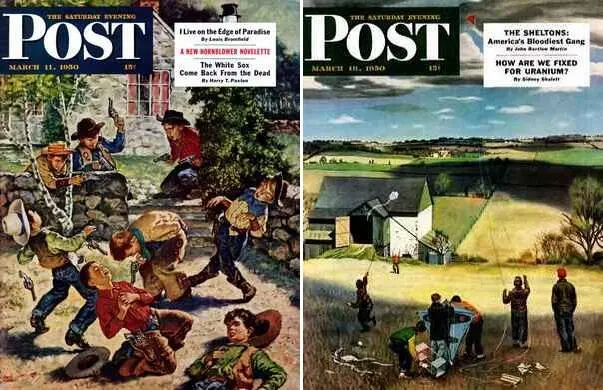

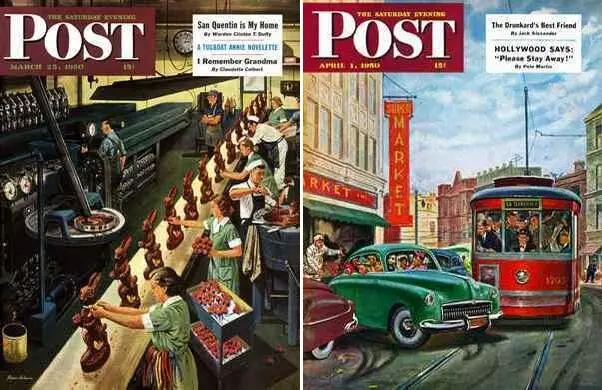

The Saturday Evening Post, February 11-April 1, 1950

Volume 222, Issues 33-40

Dawn was breaking as the first news of the disaster reached London. It was February tenth and the rattle of milk bottles was the only sound in the black, frost-bound streets. In Fleet Street a Reuter’s operator was handed a news flash and his fingers ran automatically over the keys of his machine as he transmitted the message to the subscribers. Two blocks away, in the office of a big London daily, a sleepy subeditor heard the clack of the message as it came through on the teleprinter. He tore it off and stood there reading it:

CAPE TOWN FEB to ROTTER: SOS RECEIVED FROM FACTORY SHIP SOUTHERN CROSS. SHIP IS CAUGHT IN ICE IN WEDDELL SEA AND IN DANGER OF BEING CRUSHED. NORWEGIAN FACTORY SHIP HAAKON 400 MILES FROM POSITION OF SOUTHERN CROSS GOING TO RESCUE.

REUTER 0713

The subeditor yawned, tossed the sheet of paper into the news basket. In Whitehall, at the Admiralty, a messenger hurried along the empty, echoing corridors. He handed a message to the duty officer. The duty officer rubbed the sleep out of his eyes, read the message through, placed it in a basket marked “For Immediate Attention.” In a big office block in Fenchurch Street the telephone rang incessantly on the third floor. These were the offices of the South Antarctic Whaling Company and only the cleaners were there. The telephone went unanswered. Then the call from Cape Town was transferred to the flat of Albert Jenssen, the company’s London manager.

Albert Jenssen was still in bed. The telephone woke him, and he wan half asleep as he groped for the receiver and lifted it to his ear. A moment later and he was sitting up in bed, wide awake and speaking rapidly into the phone. When he had finished, he replaced the receiver automatically and sat there for a moment, a dazed expression on his face. Then he fell upon the telephone, and call after call went out from the flat in South Kensington: cables to Durban, the Falkland Islands and the whaling stations of South Georgia; calls to Sandefjord and Tönsberg in Norway, to Leith in Scotland, to the BBC, to a cabinet minister and finally to the Admiralty.

By midday more than 150,000,000 people knew that a ship of 22,000 tons belonging to a British whaling company was locked in the grip of the Antarctic ice and was being slowly crushed, and that more than 400 men were face to face with death in the pitiless, frozen wastes of the Antarctic.

The Admiralty ordered the sloop Walrus to proceed to South Georgia, refuel and then make an attempt to reach the Southern Cross. A South African naval corvette was dispatched from Cape Town, also with orders to refuel at South Georgia. Det Norske Hvalselskab, of Sandefjord, Norway, announced that their factory ship, Haakon, which had steered for the Southern Cross within half an hour of receiving the first SOS at 0318 hours, was now within 200 miles of the ship’s last position. The United States Government offered the services of the aircraft carrier Ohio, then cruising off the River Plate.

Meanwhile events moved fast in the Antarctic. An early report that the Southern Cross had dynamited an area of clear water and was being warped round was followed by the news that the way out of the ice was blocked by several icebergs which were charging into the pack. The tanker, Josephine, and the refrigerator ship, South, were standing by on the edge of the pack, together with the rest of the South Antarctic Company’s fleet, unable to do anything. By midday the whole of the starboard side of the Southern Cross was buckling under pressure of the ice, and at 1417 hours Captain Eide, the master, gave the order to abandon ship. In a final message before unloading the radio equipment onto the ice, Eide warned the Haakon not to enter the ice beyond the line of icebergs. That was the last message received from the Southern Cross.

All that night the lights blazed in the South Antarctic Whaling Company’s offices in Fenchurch Street. But no message came through from the survivors. Utter silence had closed down on the abandoned ship and it was clear that this was the worst sea disaster in peacetime since the Titanic went down in 1912.

The most-detailed picture of the events leading up to the disaster available on the morning of the eleventh was contained in a feature article in London’s largest daily. It was headed: DISASTER IN THE ANTARCTIC, and read:

The Southern Cross left the Clyde on the sixteenth of October last with a total of 411 men and boys. In charge of the expedition was Bernt Nordahl, factory manager. Hans Eide was master, and the assistant manager was Erik Bland, son of the chairman of the South Antarctic Whaling Company. About 78 per cent of those on board were Norwegians, mainly from Sandefjord and Tönsberg. The rest were British. With her Mailed an ex-Admiralty corvette, converted to act as a whale-towing vessel, and the refrigerator ship. South.

The Southern Cross arrived at Cape Town on the fourteenth of November, where her catchers and a tanker were waiting for her. The expedition sailed on the twenty-third of November. The fleet then consisted of the factory ship, a vessel of 22,160 tons. 10 whale catchers, each of under 300 tons, two buoy boats — catchers used for towing — three ex-naval corvettes for towing whales, one refrigerator ship, one tanker, and an old whaler to transfer the meat to the refrigerator ship. One of the towing vessels was later sent back to Cape Town to pick up electric-harpoon equipment. The company intended to experiment during the season with the electrocution of whales, a method of killing that was in its infancy prior to the war.

On the twenty-ninth of November the Southern Cross sighted South Georgia and wits in radio-telephone communication with the shore-based whaling stations on this island. Reports of both Nordahl. the factory manager, and Captain Ride, the master, to the London office nil spoke of violent and incessant gales, low temperatures, loose pack ice and an unusually large number of gigantic icebergs.

Whales seemed very scarce by comparison with the previous bumper season, and on Boxing Bay. Nordahl reported trouble with the men. This is almost unheard of in Norwegian or British whaling fleets, where the men have a financial interest in the catch. But when Jenssen was pressed for fuller details, he said he had no statement to make on the matter.

The matter must have been serious, however, for Colonel Bland, chairman of the company, left London Airport on the second of January for Cape Town in a privately chartered plane. He undertook the journey against the advice of his doctors. He had been seriously ill for some time with heart trouble. With him went his daughter-in-law; Franz Weiner, a German technical adviser on the electrical harpoon; and Aldo Bonomi, the well-known photographer. The daughter-in-law, Mrs. Judie Bland, is the daughter of Bernt Nordahl.

No report was received at the London office after Colonel Bland joined the Southern Cross on the seventeenth of January, except routine reports of positions and number of whales caught. From these, however, it is clear that shortly thereafter Colonel Bland decided to steam south into the dangerous ice-strewn Weddell Sea in search of whales.

Читать дальше