“That’s not fair!” The girl’s voice blazed.

“Not fair, eh? What the devil am I to think? They weren’t a week out of Cape Town before there was trouble between them.”

“And whose fault do you suppose that was?” the girl demanded angrily.

“Bernt was playing on his lack of experience.”

“That’s Erik’s story.”

“What of that? Do you expect me not to believe my own son?”

“Yes, but you don’t know him very well, do you? You were in London all through the war, and since then—”

“I know when a toy’s being victimized!” Bland snapped back. “Why, Bernt even had the nerve to cable that he was causing trouble among the Tons berg men. There’s never any trouble with whalers. They’re far too interested in the success of the expedition.”

“If Bernt said he was causing trouble among the Jenssen men, then he was.” The girl’s voice steadied. “He’s never thought of anything but the interests of the company. You know that.”

“Then why does he send me this ultimatum? Why does he demand Erik’s recall?”

“Because he’s seen through him.”

“Seen through him? That’s a fine way to talk of your husband.”

“I don’t care. You may as well know the truth about him.”

“Shut up!” Bland’s voice was thunderous. “Don’t talk like that. I can see what’s happening to him now. You undermining him at home and your father undermining him out there. His confidence in himself is being sapped by the pair of you. No wonder he needs—”

“His confidence!” The girl’s tone was half contemptuous, half hysterical. “You don’t know him at all, do you? You still think of him as the gay, reckless boy of ten years ago — sailing his boat, winning ski-jump championships. You think that’s all he wants. Well, it isn’t. He likes to control things — men, machines, an organization. He wants power. Power, I tell you. He wants control of the company. And he’s got his mother—”

“How dare you talk like that?”

“Do you think I don’t know Erik by now?” She was leaning forward across the gangway, her body rigid, her face a white mask. “I’ve been meaning to tell you this for some time — ever since that first cable. But you were too ill. Now, if you’re well enough to travel, you’re well enough to know what—”

“I refuse to listen.” Bland was trying to keep down his anger. “Damn it, the boy’s your husband!”

“Do you think I don’t know that?” Her voice sounded frighteningly bitter. “Do you think he hasn’t made me aware of that every hour of every day we’ve been married?”

Bland was peering at her through his thick glasses. “Don’t you still love him?” he asked.

“Love him!” she cried. “I hate him! I hate him, I tell you!” She was crying wildly now. “Oh, why did you agree to send him out as second in command?”

“You seem to forget he’s my son.” Bland’s voice was ominously quiet.

“I haven’t forgotten that. But it’s time you knew the truth.”

“Then wait till we’re alone.”

The girl glanced at me and saw that I was watching her. “All right,” she said in a low voice.

“Franz!” The man next to me jerked in his seat. “Come and sit back here... Change places with Franz,” he ordered the girl. “And try to calm down.”

She got up heavily and changed places with Franz Weiner.

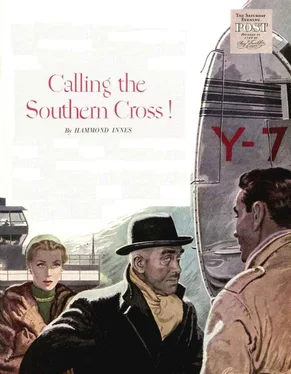

I think I was too excited to sleep. In the end I got up and went through into the pilot’s cockpit. Fenton was at the controls. Tim was pouring coffee from a vacuum flask. “Well, there’s the last you’ll see of England for a bit,” he said, nodding through the side window. “Getting on all right with Bland’s party?”

“I’ve hardly spoken to them,” I said. “Bland and the girl have just had a hell of a row. Now he’s talking to Weiner about some new equipment or something. Weiner’s German, isn’t he?”

“That’s right. He’s an expert on electrical harpoons. Poor devil! Think of it. Four months in the Antarctic.”

“Is Bland going out to the Antarctic too?”

“Yes, they’re all going, as far as I know. There’s a boat waiting for them at the Cape to take them out to the factory ship. I gather there’s some sort of trouble on board the Southern Cross. Anyway, Bland sounded as though he was in a hell of a hurry to get out there.”

“Do you mean to say the girl’s going as well?” I asked.

He shrugged his shoulders. “Don’t know about her,” he answered. “She only joined the party at the last moment. According to her papers, she’s Norwegian by birth and South African by marriage. Looks rather a poppet.”

“She doesn’t behave like one,” I answered. “More like a wildcat. And she’s all tensed up over something. It’s an odd setup.”

“You should worry. You got your ride, didn’t you? If you want company, go and talk to Aldo Bonomi. There must be something behind the bounce, for he’s one of the world’s best photographers. Like some coffee?”

“No, thanks,” I said. “I’ll sleep better without it.”

He set down the flask. “That re minds me. I’d better hand out some blankets. You might give me a hand will you, Duncan?”

Back in the main body of the plane everything was just as I’d left it. We handed round the blankets. “Breakfast at Treviso,” Tim said as he went for’ard. I settled in my seat across the gangway from the girl. She had wrapped her blankets round her, but she still sat tense and wide-eyed. My thoughts drifted to South Africa and the new world that lay ahead. What sort of job would Kramer find me when I got there? The drone of the engines gradually lulled me to sleep.

A frozen dawn showed us the Alps as a wild barrier of snow-capped peaks with the crevassed glacier ice tumbling down through giant clefts. Then we were over the flat expanse of the Lombardy plain and setting down at Treviso for breakfast.

I was right behind Bonomi as we went into the canteen. He picked a table away from the others and I seated myself opposite him. “I gather you’re a photographer, Mr. Bonomi,” I said.

“But of course. I am Aldo Bonomi. Everyone wishes for my photographs. One week I am in America, next I am in Paris. Travel, travel, travel — I am always in trains or airplanes.”

“And now you’re going to the antarctic with Colonel Bland. Tell me, what do you think of him? You heard the row he had with his daughter-in-law? Is there something wrong on board the factory ship?”

His hand fingered his little green-and-red bow tie. “Mistair Craig, I never talk about my clients. It is not good for business, you understand.” The flash of white teeth in his swarthy face was hail ingratiating, half apologetic. He smoothed his hand over the shining surface of his black hair. “Let us talk about you,” he said. The waiter came with our breakfast. As he poured the coffee. Bo no mi said, “You emigrate to South Africa, yes?”

I nodded.

“That’s very exciting. You go to another country and you start again. You have no job, but you go all the same. That needs guts, eh? You are a man with guts. I like men with guts.”

“What makes you think I haven’t got a job?” I asked as the waiter disappeared.

“If you have a job, then you do not need to ask for a ride. But tell me, what makes you leave England?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “I don’t know,” I said. “I just got fed up.”

“But something make you decide very quick, eh? Oh, I do not mean something serious, you understand. Life, she is not like that. Always it is the little things that make up our minds for us.”

I laughed at that. “You’re right there.” And suddenly I was talking to him, telling him the whole thing. “I suppose I’ve been feeling a sense of frustration ever since the war ended,” I explained. “I went straight from Oxford into the navy. When I came out I found that commanding a corvette didn’t qualify me to run a business. I finished up as a clerk with a firm of tobacco importers.”

Читать дальше