Hammond Innes

Nothing to Lose

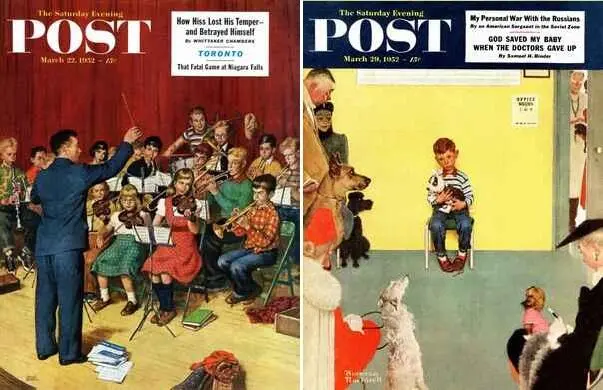

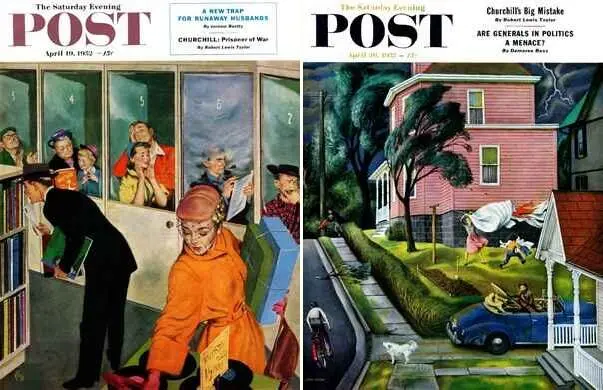

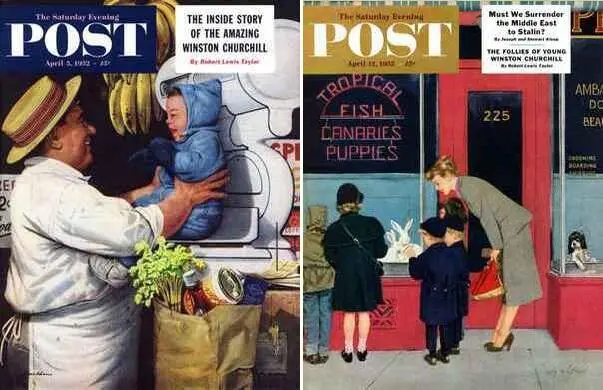

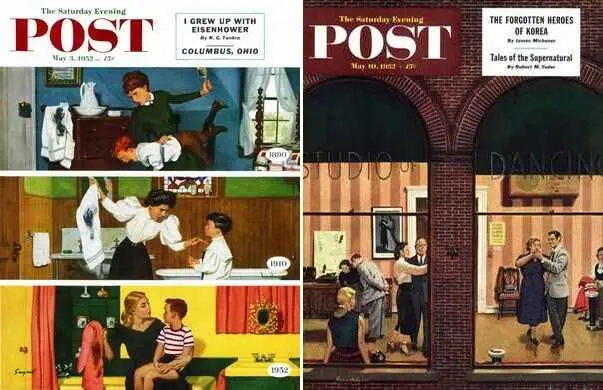

The Saturday Evening Post, March 22-May 10, 1952

Volume 224, Issues 38-45

I hesitated as I crossed the road and paused to gaze up at the familiar face of No. 32. For years I had been coming home from the office to this rather drab old Georgian-fronted house on the edge of Mecklenburgh Square, yet now I seemed to be looking at it for the first time. It was as though I were living in a dream. I suppose I was still dazed by the news.

I wondered what they’d say at the office — or should I go on as though nothing had happened? I thought of all the years I’d been leaving this house at eight-thirty-five in the morning and returning to it shortly after six at night; lonely, wasted years. Men who had served with me during the war were now in good executive positions. But for me the army had been the big chance. Once out of it, I had drifted without the drive of an objective, without the competitive urge of a close-knit masculine world.

A car hooted and I shook myself, conscious of the dreadful feeling of weariness that possessed my body; conscious, too, of a sudden urgency. I needed to make some sense out of my life, and I needed to do it quickly. As I crossed to the pavement, automatically getting out my keys, I suddenly decided I wasn’t going to tell the office anything. I wasn’t going to tell anybody. I’d just say I was taking a holiday and quietly disappear. I went in and closed the door. Footsteps sounded in the darkness of the unlighted hall.

“Is that you, Mr. Wetheral?” It was my landlady.

“Yes, Mrs. Baird.”

“Ye’re home early. Did they give ye the afternoon off?”

“Yes,” I said, wondering what she would say if I told her why.

As I started up the stairs she stopped me. “Och, I nearly forgot. There was a lawyer to see you. He ha’na been gone more than ten minutes. He said it was very important, so I told him to come back again at six. Shall I bring him up when he comes?”

“Please do,” I said as I went on up to my rooms.

For a while I paced back and forth, wondering what the devil a lawyer could want with me. Then I turned abruptly and went through into the bedroom. I was tired, I took off my coat and lay down on my bed and closed my eyes. And as I lay there sweating with fear and nervous exhaustion, my life passed before my mind’s eye, mocking me with its emptiness. Thirty-six years, and what had I done with them? What had I achieved?

I must have dropped off to sleep, for I woke with a start to hear Mrs. Baird’s voice calling me from the sitting room, “Here’s the lawyer man to see ye again, Mr. Wetheral.”

I got up, feeling dazed and chilled, and went through into the other room. He was a lawyer, all right; no mistaking the neat blue suit, the white collar, the dry, dusty air of authority.

“My name is Fothergill,” he said carefully. “Of Anstey, Fothergill and Anstey, solicitors, of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Before I state my business, it will be necessary for me to ask you a few personal questions. A matter of identity, that is all. May I sit down?”

“Of course,” I murmured. “A cigarette?”

“I don’t smoke, thank you.”

I lit one and saw that my hand was shaking. I had had too many professional interviews in the last few days.

He waited until I was settled in an easy chair and then he said, “Your Christian names, please, Mr. Wetheral.”

“Bruce Campbell.”

“Date of birth?”

“July 20, 1916.”

“Parents alive?”

“No. Both dead.”

“Your father’s Christian names, please.”

“John Henry, He died on the Somme the year I was born.”

“What were your mother’s names?”

“Eleanor Rebecca.”

“And her maiden name?”

“Campbell.”

“Did you know any of the Campbells, Mr. Wetheral?”

“Only my grandfather; I met him once.”

“Where did you meet him?”

“Coming out of prison.”

He stared at me.

“He did five years in Brixton,” I explained quickly. “He was a thief and a swindler. My mother and I met him when he came out. I was about ten at the time. We drove in a taxi straight from the prison to a boat train.” After all these years I could not keep the bitterness out of my voice. I stubbed out my cigarette. Why did he have to come asking questions on this day of all days? “Why do you want to know all this?” I demanded irritably.

“Just one more question.” He seemed quite unperturbed by my impatience. “You were in the army during the war. In France?”

“No; the desert, and then Sicily and Italy. I was a captain in the RAC.”

“Were you wounded at all?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“By heaven!” I cried, jumping to my feet. “This is too much!” My fingers had gone automatically to the scar above my heart.

“Please.” He, too, had risen to his feet and he looked quite scared. “Calm yourself, Mr. Wetheral. I was instructed to locate a Bruce Campbell Wetheral, and I am now quite satisfied that you are the man I have been looking for.”

“Well, now you’ve found me, what do you want?”

“If you’ll just be seated again for a moment—”

I dropped back into my chair and lit a cigarette from the stub of the one I had half crushed out. “Well?”

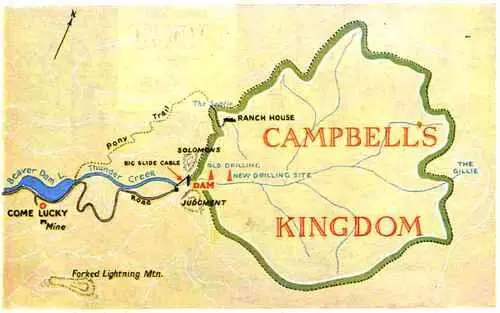

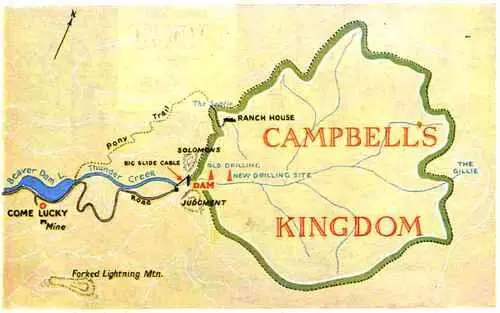

He picked up his brief case and fumbled nervously at the straps as he perched himself on the edge of the chair opposite me. “We are acting for the firm of Donald McCrae and Acheson, of Calgary, in this matter. They are the solicitors appointed under your grandfather’s will. Since you met him only once, it will possibly be of no great concern to you that he is dead. What does concern you, however, is that you are the sole legatee under his will.” He placed a document on the table between us. “That is a copy of the will, together with a sealed letter written by your grandfather and addressed to you. The original of the will is held by the solicitors in Calgary. They also hold all the documents relating to the Campbell Oil Exploration Company, together with books of the company. You now control this company, but it is virtually moribund. However, it was territory in the Rocky Mountains, and Donald McCrae and Acheson advise disposal of this asset and the winding up of the company.” He burrowed in his brief case again and came up with another document. “Now, here is a deed of sale for the territory referred to—”

I stared at him, hearing his voice droning on and remembering only how I had hated my grandfather, how all my childhood had been made miserable by that big, rawboned Scot with the violent blue eyes and close-cropped gray hair who had sat beside my mother in that taxi and whom I had seen only that once.

“You’re sure my grandfather went back to Canada?” I asked incredulously.

“Yes, yes, quite sure. He formed this company there in 1926.”

That was the year he came out of prison. “This company,” I said. “Was a man called Paul Morton involved in it with him?”

Читать дальше