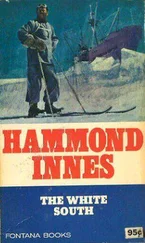

I wasn’t scared. At least it didn’t seem like fear to me then. The scene was so stupendous as to seem remote and unreal. I felt like a spectator. And I knew I should go on feeling like a spectator until the moment when I had to cross the gap and the ice overwhelmed me.

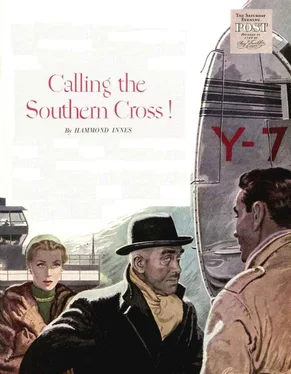

At last I, Duncan Craig, knew what it was like to look death in the face. Marooned on the antarctic ice pack with the survivors of three vessels belonging to the Southern Cross whaling ship, I could see the line of icebergs plowing slowly but violently toward our camp. Great blocks of ice were upended and crushed in the path of their advance, which moved toward us at about three miles an hour. When they reached us, we would be crushed or drowned in the icy sea.

Peer Larvik, the senior officer among us, was seriously injured and must soon die. That left me in command. I had not only to cope with the monstrous natural forces trying to destroy us but also with human violence. Erik Bland, son of the director of the whaling company, was degenerating into a madman. He would certainly challenge my right to leadership — even though he was responsible for the disaster that had stranded us. Bland’s wife, Judie, hated him. So did Walter Howe, our alcoholic oceanographer. They both knew Bland had murdered Bernt Nordahl, their father.

Bland hated me, because I loved Judie. We would have been fighting if it were not for the good sense of Gerda Petersen, daughter of one of the whaling captains. But our personal bitterness had to wait on the desperate measures we had to take to save our lives.

The dying Larvik called me to his tent. He pointed to the iceberg which was heading directly for us. If it came close enough, we might get onto the flat ledge on the side of it. That way we could ride the back of the monster and possibly survive. There was only a slim chance to cross the gap of churning ice between us and the berg, but I had to take it.

I told myself I wasn’t scared. I wouldn’t be scared until the moment came for the leap across the chasm.

Most of you who read this will have faced sudden death at one time or another. You’ll know how it feels. There is the tensing of the nerves, the sudden photographic clarity of vision. But no fear. That comes later, when nerves stretched beyond endurance relax, leaving you shivering with the reaction. If the period is too sustained, then the nervous reaction sets in before the moment of impact. Then comes fear — naked, uncontrolled fear.

That’s what happened at our camp the morning the iceberg reached us.

Just after six Judie crawled into my tent. She looked exhausted. “Duncan, will you come, please? I think he’s gone.”

I followed her to Larvik’s tent. His body was cold, and I saw that his eyes were glazed. I pulled a blanket over him.

Outside the tent I saw that many of the men had come out of their tents. They were watching us furtively and there was an air of tension over the camp. It was as though they had sensed death.

“How shall we bury him?” Judie asked.

“Leave him where he is,” I said. She started to argue, and I said, “Look at the men. They’re scared enough as it is, without knowing that Larvik is dead.”

She turned and looked round the camp. I could see there were tears in her eyes. I saw her bite her lip. Then she looked at me and nodded. “Yes, I understand. I think he will understand too.”

I turned away then and shouted for the stewards to get a meal ready. The men were silent and tense as they ate in their tents. And when it was finished they were out again in the open, staring at the crumbling ice.

The prow of the iceberg was not three hundred yards from us now. And behind the prow the ice towered up and up in sheer crags of blue and green, cold and still, until it lost itself up in the clouds.

The noise of the shattering ice was so loud that we had to shout to make ourselves heard. The floe berg was quivering. We could actually see the ice shaking. The boats rocked and the packing cases tied together rolled over. All around us the ice was breaking up now. And in a little while I should be down in the maelstrom, fighting to get a rope across to the ledge. I felt fear gripping at me.

The moment of panic came when a floe between us and the berg split across with an ear-splitting crackle. The half nearest us reared up, turning slowly on its back. For a moment it seemed poised above us, forty or fifty feet high. Then it came crashing down. Its edge splintered on the forward ledge of our refuge. A piece of ice as large as a barn door knocked one of the Hval V men flying. A great chunk was torn off our floe berg. For a moment the sea boiled black. Then the gap closed, the floes rushing together, grinding and tearing at one another.

No one moved for a moment. We were stunned by the terrible power of the forces at work. Then Hans suddenly screamed. The boy turned like a hunted hare and began to run. The men watched him for a second, immobile, fascinated. Then one of them also began to run, and in a second half the crews were following the boy.

I started forward to stop them, but Vaksdal was before me. He caught the first man and knocked him cold with one blow of his huge fist. And he got Hans — scooped the boy up with one hand and turned to face the break. The men stopped. They stood watching him for a moment like cattle that have been headed. Then they turned and shuffled shamefacedly toward the camp.

I met them as they came back. I realized that it was now or never. I couldn’t talk to them because of the noise of the splintering ice. They knelt down, all of them, and every man knelt so that he faced the advance of the berg. And as we knelt, that comforting sense of oneness developed in us — oneness of purpose in adversity. Then I looked at Judie. Her eyes met mine and smiled. And I felt sure of myself again. I could face it, whatever it was to be.

I got up and called out to the men that the moment for action had come, that now we were going to attack the berg itself. Judie was beside me, and I heard her say, “Who makes the first attempt?”

“Vaksdal and I,” I answered.

The ropes were coiled down on the ice at the side of the camp nearest the berg. I took the two ends and shouted for Vaksdal. “Because of the boats!” I shouted at him. I don’t know whether it was because he recognized the justice of my choice or because he was afraid of being regarded as a coward, but he took the rope and began to tie it round his body. I took the other rope and we went to the edge of the floe where the ice dropped in a steep slide to the quivering pack. Judie came up to me and kissed me. Then she took the rope and began to tie it around my body.

But as she started to tie it, there was a sudden surge in the crowd and she was swept aside. The rope was whipped away from me and Erik Bland slipped over the edge onto the pack ice below. He held the rope in his hand, and I can see him now as he looked up at me with a sort of crazy grin, tying the rope round his waist and calling to Vaksdal to come. I seized hold of the rope to haul him back. Whatever relief I automatically might have felt was swallowed in my instant realization of the danger of such an undisciplined action.

In that moment of hesitation I lost my one chance of stopping Bland, for as I reached for the rope again I saw it uncoiling unsteadily. Down on the ice, Vaksdal and Bland were going forward together. And then I saw that Bland was wearing crampons. Where he’d got them I don’t know. But the fact that he was wearing them made it clear that his action wasn’t done on the spur of the moment. The men were watching him intently and in some of their eyes I caught a glint of admiration.

Down on the pack the two men were moving into the broken ice. Trailing the slender lines, they climbed out on the edge of a floe that was slowly being tilted. They dropped from view. The floe rose almost vertical, hiding them. Then it broke across and subsided into the ice, showing them leaping in great bounds from one precarious foothold to another.

Читать дальше