“No,” I said.

I went down the ledge before he could argue further. Bonomi was standing by the barricade of frozen snow that marked the boundary between the two camps. I called to him. “I want to speak to Bland,” I said.

He put his finger to his lips. “I wish to speak with you.”

“Well, what is it?” I asked. I didn’t want to talk to him. I felt that he was a toady, and he looked sleek and well fed by comparison with the wraithlike figures who had crowded round me a moment ago, demanding more food.

“I wish you to know that Bland is becoming frightened,” he said. “All the time I am telling him how the men are getting desperate and how they believe he killed Nordahl and rammed your ship. At first he would tell me to shut up. Once he strike me in anger. Now he sits morose and uneasy, and all the time I am telling him how desperate the men are become. I do not think he sleep well any more.”

“Is this true, Bonomi?” I demanded.

“Do I trouble to tell it to you if it is not true? I tell you, he is becoming desperate. He is hoping all the time that the iceberg break out of the pack. The storm makes him hopeful. But now he no longer have any hope of that. I think he abandon the camp soon. There is only twenty-five more days of food left and he does not dare to reduce the rations any more.”

“Go and tell him I want a word with him,” I ordered.

He hesitated, looking a little crestfallen. I think he had expected me to congratulate him on his Machiavellian campaign.

Perhaps I should have, for when Bland came up the slope toward me, I saw his confidence was broken. He looked well fed, but his eyes were sunk in their sockets and his body seemed slack. His gaze did not easily meet mine.

“Well?” he said.

“The men are complaining about the rations,” I said.

“Let them complain,” he said.

“They’re getting desperate,” I told him. “If you’re not careful, they’ll rush the stores. You know what that means, don’t you, Bland?”

He passed his tongue quickly over his chapped lips. “I’ll shoot anyone who attempts to rush us. Tell them that, Craig. And tell them also that it’s not my fault we’re short of food.”

“They’ll believe that when they know that you’re on the same scale of rations as they are,” I answered. “How many days’ supply is left? Bonomi says only twenty-five.”

“Damn that little rat,” he muttered. “He talks too much.”

“Is that correct, Bland?”

“Yes. They’ll get the present scale of rations for twenty-five more days. That’s all. Tell them that.”

I made a quick mental calculation of the quantity of food four men, unrationed, would consume in that period. “I want thirty days’ rations for my men, three boats, together with our full share of stores and navigating equipment, by nightfall,” I said.

He stared at me, and I saw he was scared at my tone. “If you’re not careful, Craig, I’ll cut off rations completely.”

“If what I’ve asked for isn’t ready at this barrier by eighteen hundred hours tonight, I won’t answer for the consequences. That’s an ultimatum,” I added, and left him to think over what I’d said. If Bonomi had told the truth, and it certainly looked like it from Bland’s manner, then he’d do as I’d demanded.

I told the men what I’d done. For the first time in days I saw them grinning. “But it doesn’t mean the end of rationing,” I warned them. “It just means that we shall control our own rationing.”

The men gathered in hungry groups at the snow barrier. I saw Bland watching them uneasily. Just after midday the men cheered. Down in the lower camp Bland’s two mates and Bonomi had started humping stores. Bland himself kept guard with his rifle. We broke down the snow barrier, and the boats and stores were run into the upper camp. I put McPhee in charge of stores and Gerda in charge of food. Without Gerda, I think the men would have broken into the food in one glorious orgy. We were all desperately hungry.

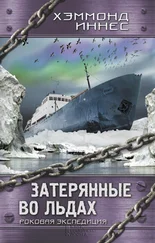

The end of the month came and went with only the entries in my log to mark the passage of time. There was a period of darkness at night now, and each day this period lengthened with amazing rapidity. But though the weather was calmer, in ten days I managed to shoot the sun only once. My calculations gave me a position of 63 31 S. 31 06 W., just about 230 miles nor’nor’east of the position at which we had abandoned the Hval IV. It gives some idea of the rate of drift.

All this time Judie was a source of worry. Her attitude was an additional weight on my mind, so that I found it very hard to shake off the increasing periods of depression. She hadn’t spoken to me since the day we had reached the ledge. She seemed to have withdrawn into herself, into a state of more or less blank misery. Gerda told me that she sometimes woke up in the night to find Judie crying and murmuring her father’s name.

“You must do something,” Gerda said to me one day. “If you do not, I think she will just fade away.” That was on March eighth. I went to Judie’s tent and tried to speak to her. She looked pale and thin, and stared at me as though she didn’t recognize me. I told Gerda to feed her some of the precious meat extract that had been included among the rations Bland had handed over to us. I left the tent in a mood of utter despair.

That was the day the aircraft flew over us. It was an American plane — the star markings were plainly visible as it passed over at about 500 feet. We had nothing to signal with, and half blanketed in snow on the sheer flank of the iceberg, it was hardly surprising that they did not see us. We piled inflammable stores together and kept constant watch in a fever of excitement and renewed hope. Two days later we saw another plane, away to the south. I picked it up in the glasses, but it was too far for our smoke to be visible and I would not give the order to ignite our precious reserves of fuel. Sleet and snow followed and we never saw another glimpse of the search planes. The monotony of hunger, cold and dying hope settled on the camp.

There were no storms now. Just the everlasting glare of low clouds and the night lengthening with the increasing cold. The steadily falling temperature was magnified by lack of food and our decreasing resistance. The men no longer looked hungrily at the lower camp, for through Bonomi we knew that their ration scale was as low as ours. Daily I checked the stores and watched our meager reserves dwindle. The lookout no longer searched the sky for planes, but peered at the ice through eyes inflamed by the constant glare, searching for some sign of life — seal or penguin, anything that would do for food. The movement of the berg through the ice gradually slowed. Everything was much quieter; the silence of death seemed to be settling over us.

March nineteenth carries the following entry in my log:

Reduced rations still further. Grieg dead. Broken rib probably pierced his lung. Has been weakening for a long time. Slipped his body over the edge as though burying at sea, none of us having the strength to cut a grave in the snow, which is hard like ice. Very cold. Wind has dropped and iceberg now stationary in pack. No hope now of breaking out to open sea.

I knew it was time for the last desperate effort I had been planning. Gerda apparently had the same thought. She came to my tent the next morning. As she sat there in the dim light I was surprised to see how much weight she had lost. Howe was with her, thin as a wraith under the bulk of his clothes, his ugliness lost in the ascetic sunken appearance of his features.

“Duncan, it is time we do something,” Gerda said. “We cannot just stay here waiting for death.”

I nodded. “I’ve been thinking the same thing,” I said.

Читать дальше