Bland spoke to him sharply. The man’s face darkened. “Ja... Herr Direktor,” he muttered, and slid down the ladder to the deck below. Bland said something violent under his breath and walked to the starboard wing of the bridge. He stood there alone, peering out over the side, until Howe appeared.

Howe looked thin as a wraith beside the squat bulk of the company’s chairman. He had a weak growth of beard that looked untidy on his queer face, and his eyes were bloodshot. But he was sober. Standing in front of Bland, he seemed nervous, as though, without liquor inside him, he found it difficult to face the man.

“For the last four years Nordahl has employed you as a scientist,” Bland rumbled, his small eyes looking the other up and down with marked distaste. “Now it’s up to you to justify that appointment. Conditions out here this summer are abnormal. The last report we had from the Southern Cross spoke of few whales. We’ve seen none. By tomorrow morning I want a report from you on the probable movement of whales in these conditions. Your continued employment will depend on your usefulness to the company. Now get to work.”

Bland turned on his heel. Howe hesitated. I knew what he wanted to say. He wanted to tell Bland that it was unfair to expect the impossible, that the very abnormality of the conditions made it so. He was being blackmailed and he knew it. Bland wanted whales. Howe was to produce them, like a conjurer, or be sacked. He turned and stumbled past me to the bridge ladder.

Shortly afterward Bland went below. An hour later, Bonomi called up to me to say that, the radio was working. I left the coxs’n on the bridge and stumbled wearily down to the deck below. My eyes were bleary with lack of sleep and the strain of staring into days of wind and sleet. Bland and Judie were in the wireless room. Judie had dark circles of strain under her eyes. But her smile of greeting was warm and friendly.

“You must be dead,” she said.

“The daily flask of brandy was a great help,” I said.

She looked away quickly, as though she hadn’t wanted to be thanked. Bland turned his big head toward me. “Just trying to get the Southern Cross on the R-T,” he said. “We’ve been speaking to the Haakon — one of the Sandefjord factory ships. She’s got eight whales in the last ten days. Now she’s steaming south toward the Weddell Sea. Hanssen, the master, says he’s never known conditions like this. He’s about three hundred miles west-sou’west of us.”

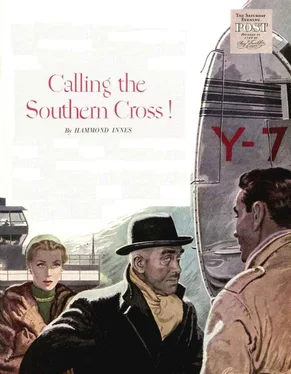

The radio crackled. Then, clear and distinct, came a voice speaking in Norwegian. I guessed it must be the Southern Cross, for Bland stiffened and his head jerked round toward the receiver. The radio operator leaned down toward the mike. There was a quick exchange in Norwegian and then he turned to Bland. “I have Captain Eide for you,” he said, and passed the microphone across to him. The chairman’s thick fingers closed round the grip. “Bland here. Is that Captain Eide?”

“Yes, sir. This is Eide.” The voice crackled in singsong English faintly reminiscent of a Welsh accent.

“What’s your position?” I nodded for Sparks to take it down. Fifty-eight point three four South, thirty-four point five six West. I made a swift mental calculation. Bland’s eyebrows lifted in my direction. “That’s about forty miles west of us,” I said. He nodded and resumed his conversation — this time in Norwegian. My eyelids became unbearably heavy. Sleep rolled my head against the wood paneling of the cabin wall.

Then suddenly I was awake again. A new voice was talking over the radio, talking in English. “They’re holding out for an inquiry. I’ve told them there isn’t going to be any inquiry. It’s a waste of time. There’s nothing to inquire into. Nordahl’s gone, and that’s all there is to it.” It was an easy, cultured voice — smooth, like an expensive car. But it was just a veneer. It revealed nothing of its owner. “The real trouble is that the season’s been terrible. Even the Sandefjord men are grumbling. As for the Tönsberg crowd, they’re more nuisance than they’re worth. If you hadn’t been coming out, I’d have sent the whole lot home.”

“We’ll talk about that when I see you, Erik,” Bland cut in, his voice an angry rumble. “How many whales have you caught so far?”

“Fin whales? A hundred and twenty-seven... that’s all. The fog’s just beginning to lift now. Perhaps the luck will change. But there’s pack ice to the southeast of us and the men don’t like it. They say conditions are abnormal.”

“I know all about that,” said Bland. “What are your plans?”

“We’re cruising east now along the northern edge of the pack. We’ll just have to hope for the best.”

“Hope for the best!” Bland’s cheeks quivered. “You get out and find whales... and find ’em damn quick, boy. Every day without a whale is a disaster. Do you understand?”

“If you think you can find them when I can’t — well, you’re welcome to come and try!” The voice sounded sharp and resentful.

Bland gave an angry grunt. “If Nordahl were alive—”

“Don’t you start throwing Nordahl at me!” his son interrupted in a tone of sudden violence. “I’m sick of hearing about him!”

“We’II be with you in a few hours now,” Bland said soothingly. “We’ll talk about it then. Put Eide back on.” Eide’s voice was comfortingly calm. He spoke in Norwegian, and Bland was answering him in the same language. There was a pause. Then suddenly his voice was back in the cabin again, shouting, “Hval! Hval! En av hvalbaatene hur set hval!” Bland’s face relaxed. He was smiling. Everyone in the cabin was smiling.

I looked at Judie. She leaned toward me, and I saw that even she was excited. They’ve sighted whales.” She turned her head to the radio again, and then added, “They have seen several pods. They are all going south... into the ice.”

“How many whales to a pod?” I asked.

She laughed. “Depends on the sort of whale. Only one or two in the case of the blue whale. But three to five for the fin whale.” She shook her head. “But it’s bad for them to be going south.”

The skipper of the Southern Cross signed off and Bland turned to me. “You got their position?” he asked.

I nodded and got stiffly to my feet. Sparks handed me a slip of paper on which he’d written the present position and course of the Southern Cross. I climbed up to the bridge and laid our course to meet up with the factory ship. Tauer III turned, heeling slightly as the helmsman swung her on to the new bearing. I told the coxs’n to wake me in four hours’ time, and went below for the first real sleep I’d had in eight days.

But I didn’t get my full four hours. The messboy woke me just after midday and I dragged myself up to the bridge. The coxs’n was there, sniffing the air.

“You smell something, ja?” He was grinning. I smelled it at once — a queer, heavy smell like a coal by-product. “Now you smell money,” he said. “That is whale.”

“The Southern Cross?”

“Yes.”

“How far away?”

“Fifteen... maybe twenty mile.”

“Good grief!” I said. I was imagining what the smell must be like close to. An hour later the fog began to lift and I ordered full speed. Slowly the fog cleared, revealing a bleak ice-green sea heaving morosely under a low layer of cloud. Away to the southeast I got my first sight of the ice blink. This was the sight striking up from close pack ice, its surface mirrored in the cloud. The effect was one of brilliant whiteness criss-crossed with dark seams. The lark seams were the water lanes cutting through between the floes, all faithfully mapped out in the cloud mirror above it.

Bonomi was up on the bridge with his camera. When I’d worked out our position and sent a lookout to the masthead, he came across to me. “You feel good now, eh? Everything is fine.” He grinned. His cheerfulness added to the sense of depression that had been growing up inside me. I wasn’t looking forward to closing with the Southern Cross. For one thing, it meant the end of my temporary command. For another — well, all I can say is that I had developed an uneasy feeling about the Southern Cross.

Читать дальше