The skipper of the factory ship hesitated. Then he said, “He is on the foreplan. He could not come.”

Bland grunted. “He’s got assistants, hasn’t he?” he growled.

I must say that at that moment I felt some sympathy for Erik Bland. Whatever the man’s nature, he’d certainly been handed a tough job, and I didn’t blame him for staying up on the fore-plan. I looked at Judie to see whether she was feeling sympathy for her husband’s position. But she was staring up at the towering, ugly bulk of the Southern Cross, and I realized that her thoughts were on her father.

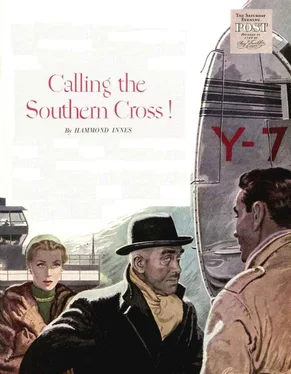

I left my clerk’s job in London because I couldn’t stand the dullness. I begged a ride in a private plane bound for Cape Town, South Africa. Colonel Bland, director of the South Antarctic Whaling Company, was headed for polar waters to investigate reports of trouble among the men on the huge factory ship. Southern Cross. I introduced myself to him as Duncan Craig and told him I had once been commander of a corvette in the war. In Cape Town the skipper of the corvette-type whale catcher that was to take Bland to the factory ship had been injured. Bland offered me temporary command, and I accepted.

Bland’s daughter-in-law, Judie, accompanied him, and so did the Italian photographer, Aldo Bonomi. Judie hated her husband, Erik, who shared control of operations on the Southern Cross with Bernt Nordahl, Judie’s father. Before we reached Cape Town we learned that Nordahl had been mysteriously lost overboard from the big ship, and I knew Judie suspected that Erik might be responsible.

From Cape Town we ran into vicious weather, and I had little time for anything but the ship — although I got to know Howe, the marine scientist of the expedition. Howe was a drunkard and devoted to the late Bernt Nordahl. He hated Colonel Bland. He seemed to hold Bland guilty of Nordahl’s death.

When we made rendezvous with the Southern Cross, I became acquainted with the smell of whales — thick, overpowering and nauseating. Captain Eide, the officer in command of the big ship, came aboard our little vessel. He told Bland the men were demanding an investigation of Nordahl’s death, that whales were scarce and that trouble was coming.

Bland turned to me. “Craig,” he said, “you’ll come with us. Before you know where you are, you’ll lie in charge of a catcher.”

I wasn’t present at the meeting between Bland and the skippers of the Tönsberg catchers. But I saw them leave and I got the impression that Bland had given them something to think about. They were tough, bearded men with fur caps on their heads, thick jerseys under their wind breakers and feet encased in knee-length boots.

I was being conducted round the ship at the time. My guide had taken me first to the flensing decks. This is the center of activity in a factory ship when the whales are coming in. There are two flensing decks — the fore-plan and the after-plan. And both looked like the sort of charnel house you might dream up in a nightmare. The winches clattered incessantly. Men with huge iron hooks dragged blubber, meat and bone to the chutes that took it to the boilers to be tried out and the precious oil extracted. The noise and the smell were indescribable. And the work went on as whale after whale was dragged up the slipway, the men working like demons and the decks slippery with blood and grease.

I want to give a clear impression of this ship, because only then is it possible to appreciate the shock of what happened later. She was a floating factory — a belching, stinking muck heap of activity two thousand miles from civilization. And over everything hung the awful smell of whale. But though her decks might present the appearance of some Gargantuan slaughterhouse, below all was neat and ordered. There were the refrigeration plant and machinery for cutting and dehydrating and packing the meat. There were crushing machines for converting the bone to fertilizer. There were laboratories and workshops, sick bays, mess rooms, living quarters, store rooms, electric-generating plant — everything. The Southern Cross was a well-stocked, well-populated factory town.

When we got up on deck again, the whole fleet was in action, with whales spouting all around us. It was an incredible sight. I saw one catcher quite close. The skytter was running down the catwalk that connected the bridge with the gun platform perched precariously on the high bows. He seized the gun, his legs braced apart, waiting for the moment to strike. Twice the catcher drove the whale under. Then suddenly the spout was right under the catcher’s bow. I saw the sharp-ended point of the harpoon dip as the gun was aimed. Then it flew out — a hundred-and-fifty-pound, javelinlike projectile with a light forerunner snaking after it. There was the sharp crack of the gun and then the duller boom of the warhead exploding inside the whale as it sounded. The next moment the line was taut, dragging at the masthead shackles and accumulator springs as the heavy line ran out and the winch brakes screamed. The whole thing took on the proportions of a naval operation.

But by this time my stomach was in open revolt. I thanked my guide hurriedly and staggered off to my cabin. I gave up all I had and, cold with sweat, fell into an exhausted sleep on my bunk. I didn’t wake up until Kyrre, the second officer, came in.

He grinned at me as I opened my eyes. “You are ill, yes?” The corners of his eyes creased in a thousand wrinkles and he roared with laughter. “Soon you are better,” he added. “No more whale.”

“You mean you’ve finished catching for the day.” I struggled up on to my elbow. I felt weak, but my stomach was all right now.

“Finish for the day, ja.” His eyes suddenly lost their laughter. “Finish altogether, I think.” he said “The whale go south. It is what you say, the migration.” He shook his big head. “Maybe we have to go south too.”

“That means going through the pack ice, doesn’t it?” I said, putting my feet over the side of the hunk.

“Ja,” he said, and his eyes looked troubled. “ Ja, through the pack ice. It is bad, this season. The Haakon she is going south already. We go also, I think.” Then suddenly he grinned and clapped me on the back. “Come, my friend. We go to eat, eh?” The officers’ mess was plain and well scrubbed, the predominating note bleak cleanliness. Most of the men wore beards. They didn’t talk. But a sense of tension brooded over the table. Covert glances were cast at Bland where he sat, with Judie on one side of him and Eide on the other. Judie was toying with her soup. Her eyes were blank. The man next to her made some remark. She ignored it.

“Which is Erik Bland?” I asked my companion. It was as I had guessed. The man sitting next to Judie was her husband. He was taller and much slimmer than his father, but he had the same round head and short, thick neck. But there wasn’t the same strength. There was no violent set of jaw, no dragging down of the brows from a wide forehead. Instead there was a sort of arrogance.

When the meal was over, Eide asked me to have a drink with him. He took me to his cabin and we talked about the war. At length I brought the conversation round to Nordahl’s disappearance. But all he’d say was “It’s a complete mystery. I don’t understand it at all.”

“What’s your opinion of Erik Bland?” I asked.

“How do you mean?” he asked guardedly.

“I gathered he’d been causing trouble with the Tönsberg men.”

Eide’s brows lifted. “On the contrary. He’s done everything to smooth things over. He’s young, of course, and inexperienced. But that’s not his fault. He’ll learn. And a lot of the men like him.”

“But he didn’t get on with Nordahl, did he?”

Читать дальше